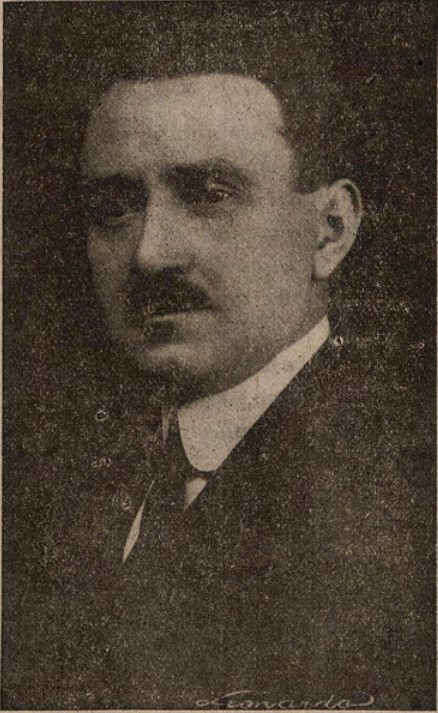

Solomon Haliță (1859–1926)

Image source: here.

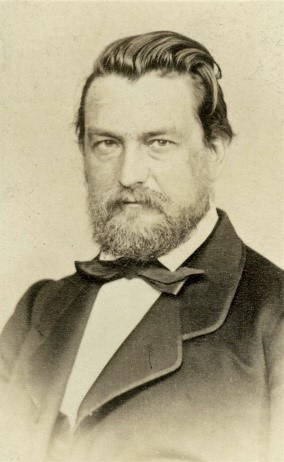

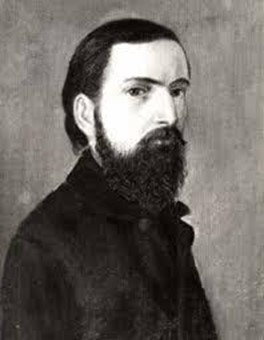

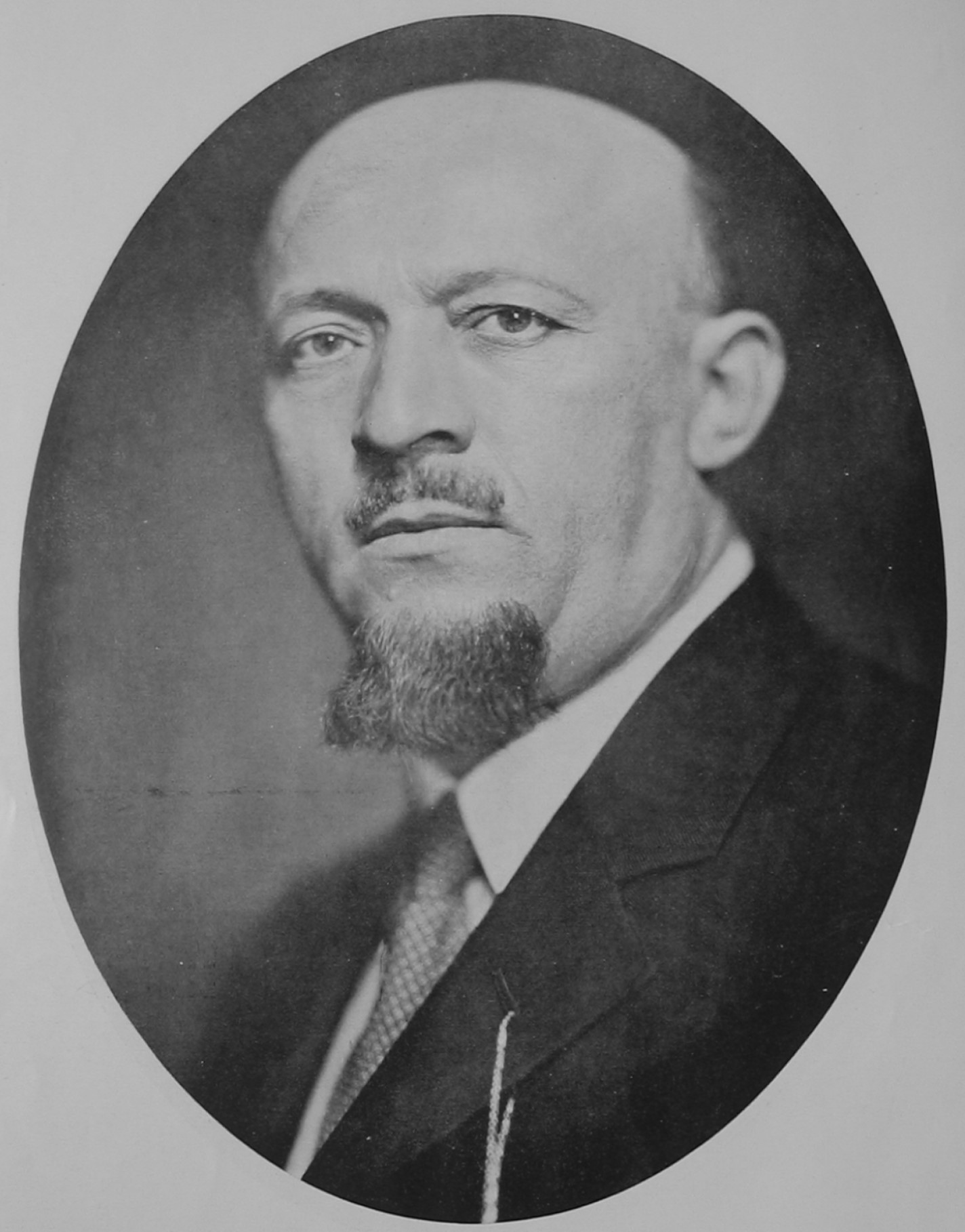

Maxim Haliță (1826–1893) came from a border guards family in Sângeorz Băi (Sângeorzul Român, Oláhszentgyörgy). He started as a village teacher during the 1840s, then served in the 17th (2nd Romanian) Border Guards Regiment during the Revolution of 1848–1849. After the military border system in the area was decommissioned he started a career in local administration: village notary (1851–1872), clerk to the district sheriff’s office (1873–1873), district sheriff (1873–1875), royal head-postman (1875–1889). In 1852 he married Ileana Ciocan (adopted by the family Isipoaie), and fathered four children: Elisabeta (1853–1915), Axente (1856–1865), Solomon (1859–1926) and Alexandru (1862–1933). (more, here)

His children were part of the first generation of young people who benefited from financial support for their studies, provided by the Border Guards’ Funds, an institution created following the decommission of the military border.

Elisabeta studied at the girls’ school in Năsăud (Naszód), then in Bistrița (Bistritz, Beszterce) and married Grigore Marica, a priest from Coșna – a nearby village. In 1879, her husband died after being accidentally wounded by her brother, Solomon Haliță (20 years old at the time), while returning from a hunting trip. As a consequence, Solomon vowed not to marry and have children, but to raise his three orphaned nephews, which he did, supporting them throughout their life. (more, here)

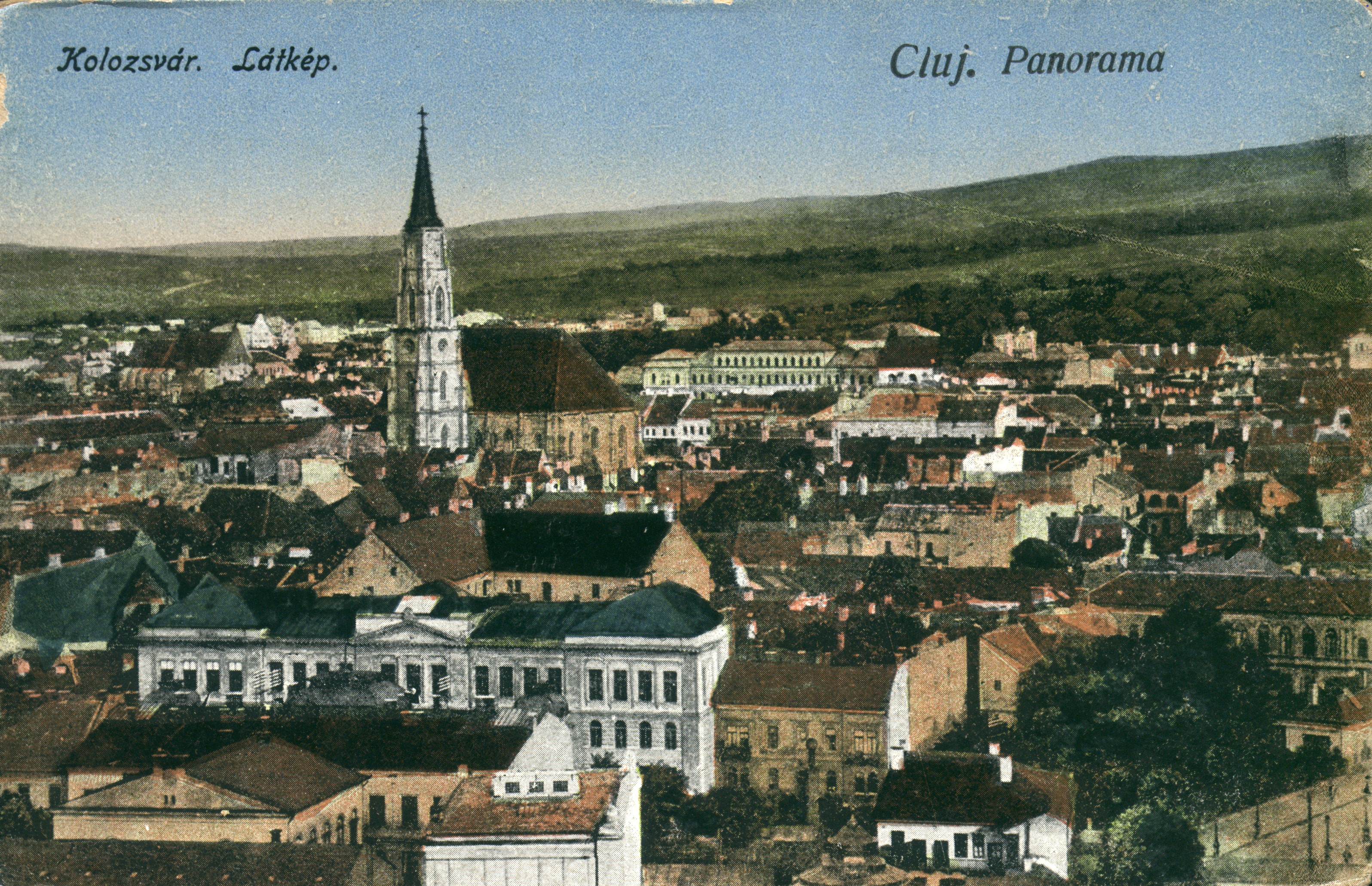

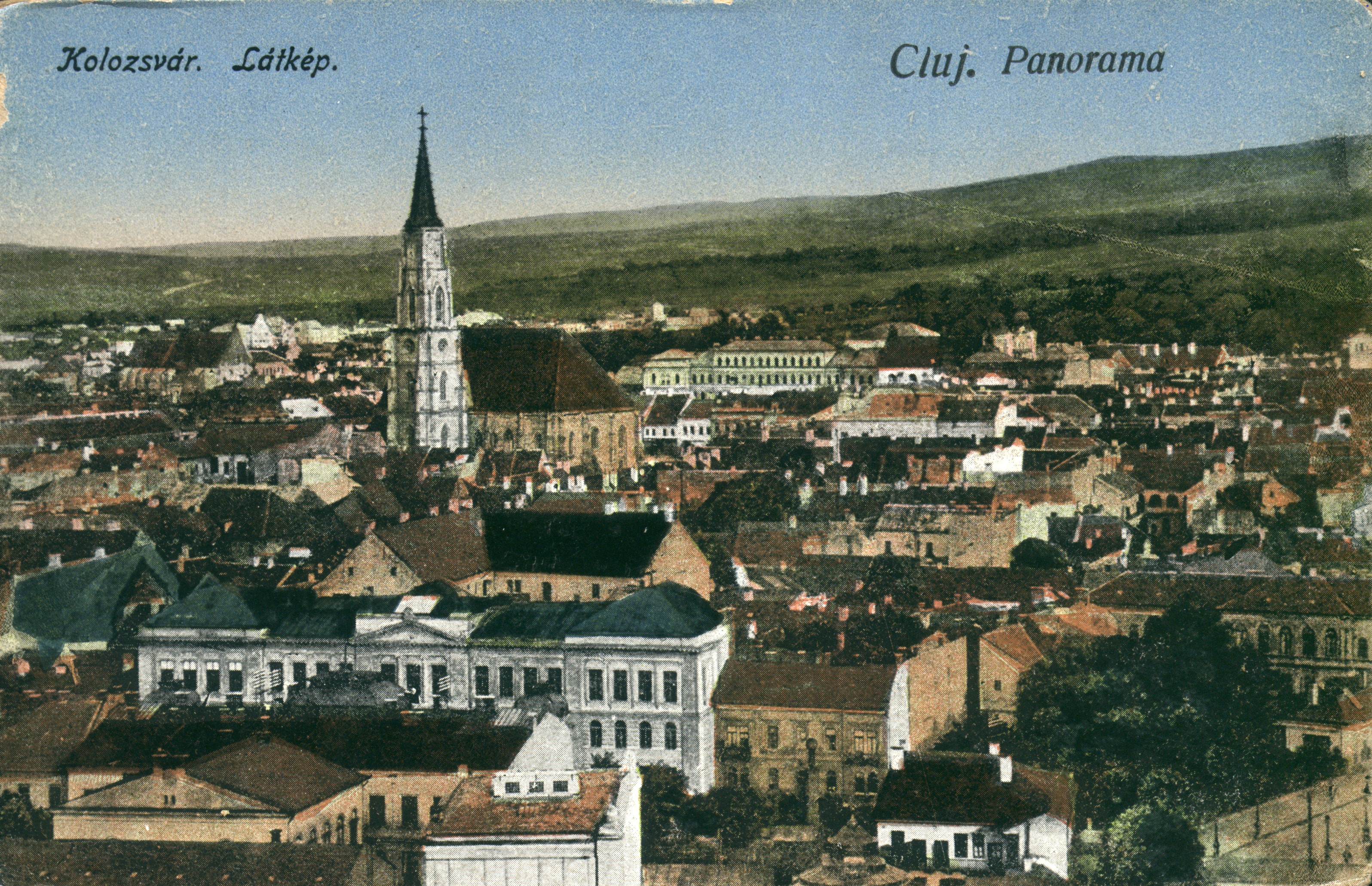

The youngest son, Alexander, studied Greek-Catholic Theology at Gherla (Szamosújvár) (1884–1888) and Letters at the Francis Joseph University in Cluj (Kolozsvár) (1888–1893). He was a teacher at the Highschool in Năsăud (1891–1911, 1920–1928), as well as parish priest of Năsăud and curate of Rodna (1911–1920). (more, here)

The best-known member of the family, however, was to become Solomon Haliță. He studied at the Highschool in Năsăud, where he distinguished himself and was also actively involved in the school’s literary societies (both the authorized and the secret ones). These societies were at the time a hotbed of Romanian nationalism and some of Haliță’s colleagues (Ioan Macavei (1859–1894), Corneliu Pop Păcurariu (1858–1904)) would later become journalists of the radical nationalist political newspaper “Tribuna”, and would spend time in prison for their articles. Haliță went on to study History and Philosophy, and Pedagogy at the University in Vienna, where he joined the Romanian Students’ Society “România Jună”, but also a smaller literary club called “Arborele” (The Tree), of only 17 members. The main objective of this club was to spread the cultural ideas from the Old Kingdom of Romania (in particular those of the “Junimea” Society) among the Romanians in Transylvania. (more, here) It is worth noting that more than half of its members later became public figures in the Romanian cultural and political milieu, and at least one of them (Septimiu Albini) linked up with Haliță’s former high school mates in the editorial office of “Tribuna”, and later also served time for press offences. (more, here)

After completing his studies in 1883, Haliță had difficulties finding a tenured teaching position back home, although, truth be told, he did not seem to have the patience to wait for an opening, as he emigrated very soon to Romania. In 1890 he renounced his Hungarian citizenship and became a citizen of the Kingdom of Romania. Between 1883 and 1919 he worked as a secondary school teacher in various towns, while at the same time building a bureaucratic career in the field of Public Education: 1889–1891, member of the General [i.e., National] Council of Instruction; 1896–1899, 1901–1904, 1907–1911, and 1914–1919 General Inspector of Schools. Much of his success was owed to the good relationship he developed with Spiru Haret, an important liberal reformer of education in early 20th century Romania. (more, here)

During the First World War, and especially during the retreat of the Romanian political authorities to Iași (1916–1918) Haliță developed even closer ties with representatives of the National Liberal Party, and in particular with Prime Minister, Ion I.C. Brătianu. Thus, he slowly shifted from being just an efficient and well-regarded bureaucrat in the field of Education to handling more sensitive political issues. In October 1918, he played the role of intercessor between the Romanian delegates from Transylvania and the Romanian government. He was then sent back to Transylvania to accompany Brătianu’s messages of political and military support and took part, in this capacity, at the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918. (more, here) This privileged position explains his temporary appointment as prefect of Iași in 1919. (more, here)

Between 1920 and 1922 Haliță returned to Transylvania as General (i.e., Regional) Inspector of Schools. In 1922 he was appointed prefect of his home county, Năsăud (Bistrița-Năsăud after 1925), an office he held until the fall of the Liberal government in April 1926. It was the peak of his career, something nobody would have envisioned forty years earlier, when he had left the same county as an émigré due to not finding a tenured teaching position. He died a few months later, on 1 December 1926.

Solomon Haliță’s career highlights the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the financial support for education in the former Austrian military border area, due to the transformation of regimental funds into educational and scholarship funds. It also illustrates the constant migration of Romanian university graduates from Austria-Hungary to Romania, which populated the civil service of the latter with highly qualified personnel, at all levels and in all branches of activity. Last but not least, it shows how the combination between professionalism and personal relationships (also built along professional lines), helped maintain a high bureaucratic position despite the changes in government, and how political support helped the leap from the ministerial bureaucracy to the administrative and political elite.

Literature

Septimiu Albini, Direcția nouă în Ardeal. Constatări și amintiri, in vol. Lui Ion Bianu amintire. Din partea foștilor și actualilor funcționari ai Academiei Române la împlinirea a șasezeci de ani, București, 1916. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban, Maxim Haliță – locuitor de frunte din Sângeorgiul Român, în „Arhiva Someșană”, XV, 2017. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban (ed.), Solomon Haliță, om al epocii sale, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2015. (here)

Ironim Marţian, Figuri de dascăli năsăudeni şi bistriţeni, Editura Napoca Star, Cluj–Napoca, 2002.

Adrian Onofreiu, Ana Maria Băndean, Prefecții județului Bistrița–Năsăud (1919–1950; 1990–2014). Ipostaze, imagini, mărturii, Bistrița, Charmides, 2014.

Grigore Pletosu, Moarte prin puşcă, în „Telegraful Român”, XXVII, 1879, nr. 91, 7 august, p. 359. (here)

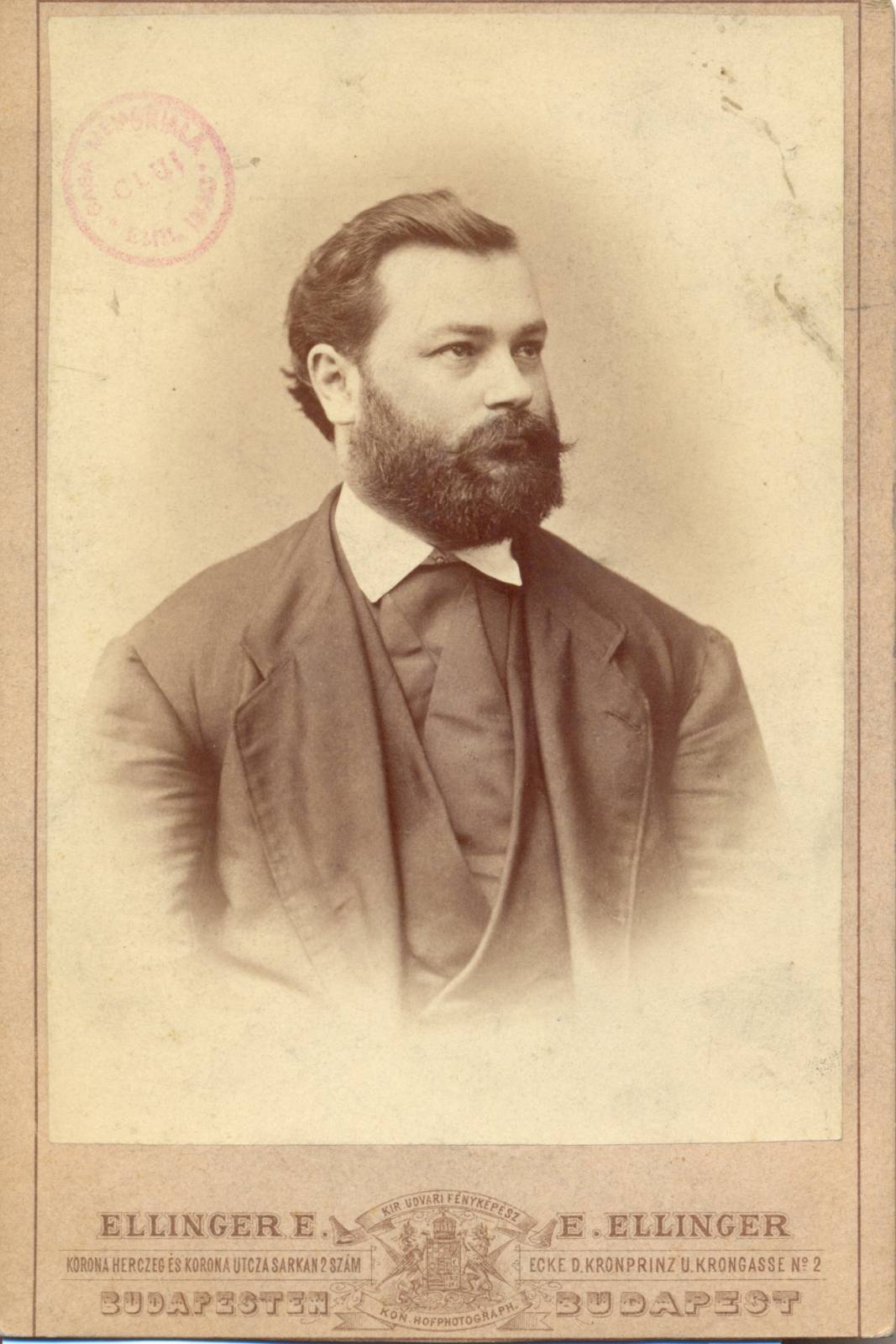

Mara Lőrinc of Felsőszálláspatak/Sălașu de Sus was born in 1823 in Székelyföldvár/ Războieni-Cetate (by then in the Székely seat of Aranyos/Arieș, Transylvania).

His grandfather, bearing the same name, was assessor at the Royal Judicial Court of Transylvania. An uncle bearing the same name was officer during the Napoleonic Wars. His father, József, was provincial commissioner and later on royal judge of the respective seat, but the family also held land properties in Hunyad/Hunedoara county. He had seven children: six boys (Miklós, Lőrinc, Károly, Gábor, Sándor and György) and one girl (Ágnes, married to baron Kemény István).

Mara Lőrinc followed a military career, he graduated from the Imperial and Royal Technical Military Academy (k.u.k. Technische Militärakademie, further reading here) and served as Junior Lieutenant in the Székely Border Guards Regiment from Csíkszereda/Miercurea Ciuc. During the 1848–1849 Revolution he served as captain in the Hungarian Honvéd Army, together with other members of the extended family (e.g., here), for which he was initially sentenced to death, but later pardoned after four years of imprisonment at Olomouc/Olmütz. In the 1860s he entered political life, as district sheriff (szolgabíró) and county commissioner (alispán). As a follower of Tisza Kálmán’s (1830–1902) party, and after two unsuccessful candidacies he finally managed to obtain a parliamentary seat in 1875, in the constituency of Hátszeg/Hațeg (in which the family estates were situated), after his party’s coming to power. He represented the constituency between 1875 and 1886 (see here), and died in 1893.

Mara Lőrinc was an epitome of Tisza Kálmán’s “mamelukes” – as the supporters of the Hungarian Liberal Party were called at the time – and the literary works of Mikszáth Kálmán (1847–1910) shed some light on the intricacies of his relationship with the voters, most of them Romanian villagers. Mikszáth recounts that, when one of the opposition’s candidates Kaas Ivor (1842–1910) and his supporters (some local Armenian merchants and the family of the ex-Prime Minister Lónyay Menyhért (1822–1884) tried to bribe the voters by means of bank checks instead of the usual cash in hand, Mara’s electoral agents redeemed to the villagers the bank checks’ value in cash and with this, he won the elections by making use mostly of his opponent’s money and supported by the supposedly nationally entrenched Romanians. At the time (1881), the story made its way in the regional and central newspapers, which might be the original source of Mikszáth’s story. Three years later, on the eve of a new election, a delegation of Romanian voters came to see their representative. He greeted them and asked about their wishes and requests for the upcoming elections, only to find out that they were humbly asking him to provide… a counter-candidate. When the mesmerized deputy asked for the purpose of such a request, the villagers’ leader replied: “…well, to have some joy in the district.” The trope of the voters asking for a counter-candidate mainly for the purpose of raising the stake of the electoral bribe is rather frequent in the time’s literature and press, here however it was used for underlining the connection between a local patron and his pool of voters. In Mikszáth’s story, Mara granted them this wish too. Historical sources show that Mara went on for another mandate, with the counter-candidate (Kemény Miklós) only getting seven votes.

As all literary sources, Mikszáth’s story was probably built around a grain of truth, despite the author’s inevitable fictional contribution. The story sheds some light not only on the voting practices of the time, but also on the voters’ expectations (i.e. the electoral campaign as a moment of feast and joy) and on the paternalistic relations enhanced by political needs.

One of his sons, also bearing the name Lőrinc, was an architect. He was married to Berta Zalandak.

Another son, László Mara, was Lord Lieutenant of Hunyad County during the First World War. In this capacity, he intervened for the liberation of a Romanian lawyer and reserve officer named Gheorghe Dubleșiu, who was imprisoned due to his nationalist rhetoric. A few years later, under the Romanian rule, Gheorghe Dubleșiu would become Prefect (i.e., Lord Lieutenant) of the Hunyad County in 1920 and between 1922–1926.

Sources:

Press

“A Hon”, XIX, 1881, 6 July, no. 184.

“Magyar Polgár”, XV, 1881, 5 July, no. 150, p. 1;

Literature

Mikszáth Kálmán, “Összes műve. Cikkek és karcolatok (51–86. kötet). 1883 Parlamenti karcolatok (68. kötet). A t. házból [márc. 9.]. IV. A Mara Lőrinc emberei”, electronic edition on https://www.arcanum.hu;

Lajos Kelemen, A felsőszálláspataki Marák családi krónikája, Genealógiai Füzetek, 1912, pp. 97-10;

József Szinnyei, “Magyar írók élete és munkái”, electronic edition on https://www.arcanum.hu.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.

Count Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly, graphic from the portrait collection of the Austrian National Library

Count Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly, graphic from the portrait collection of the Austrian National Library

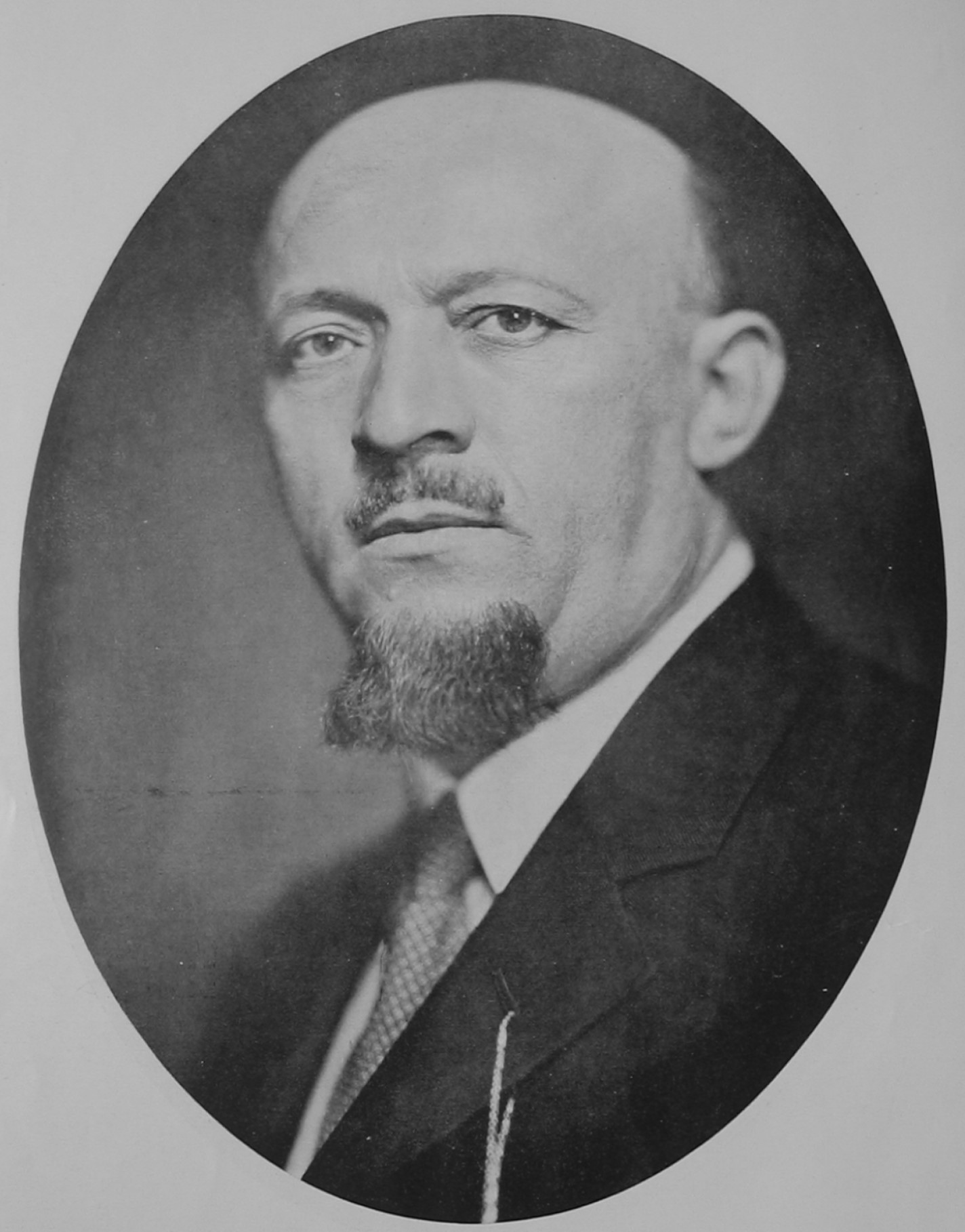

The life of Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly was fundamentally different from that of other officials. He came from an old aristocratic family, the Pouilly, which left their homeland during the French Revolution. Thus, Alexander’s father Emanuel (1777–1852) had to build a position for himself in a completely different environment. He opted for a military career in the service of the Austrian Emperor and, like his brother, decided to take the name Mensdorff, which was supposed to help him to better adapt in the German-speaking world. His marriage to Princess Sophie of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1778–1835), who was of a substantially higher status, undoubtedly also helped him consolidate his position. Thanks to this marriage, Emmanuel and his descendants became related to a number of European noble families. Perhaps the most famous among his male cousins was Albert (1819–1861), husband of Queen Victoria of Britain (1819–1901), while the most famous female cousin was Queen Victoria herself. The loving union of Emmanuel and Sophie produced five sons, four of whom survived to adulthood – Hugo (1806–1847), Alphonse (1810–1894), Alexander (1813–1871) and Arthur (1817–1904). Their life trajectories show how varied the fates of 19th-century nobility could be.

Coat of arms of the family Mensdorff Pouilly

Coat of arms of the family Mensdorff Pouilly

The eldest of the brothers, Hugo, was born in Coburg on August 24, 1806. Coburg was also the city where he grew up and received a private education. Emanuel wished to make military officers of his sons, and he succeeded. Hugo joined the army and became a cavalry officer. Although he was the eldest son and it was primarily him who was expected to ensure the continuation of the family, Hugo never married. He was no stranger to the company of women, but he did not meet a suitable partner from the upper classes. He preferred to remain alone rather than live in an unhappy marriage. During his military career, he won numerous awards and reached the rank of colonel. In 1847, however, his health began to fail. He was treated at a spa, first in Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) and then in Jeseník (Freiwaldau), where he succumbed to laryngitis at the age of only 41.

The second-born Alphonse was born on 25 January 1810 in Coburg. His father intended a naval career for him. However, Alfonse refused and became an officer in the cavalry, where he attained the rank of colonel. A crucial issue for a man of his position was the choice of a bride. Alphonse seems to have had a lucky hand, since the woman he chose, Therese Dietrichstein (1823–1856), not only came from a good family, but there was also a mutual liking between them. The bride’s father, Franz Xaver of Dietrichstein (1774–1850), was initially not very enthusiastic about the match, hoping for a husband of a higher social position for his daughter. In the end, however, he agreed to their union. After Therese Dietrichstein became the heiress of the Moravian estate of Boskovice (Boskowitz), Alfons abandoned his military career and threw himself into the administration of the estate. For several years, during which they had four children, Alfonse and Therese lived a happy family life in Boskovice In 1856, however, tragedy struck the family – Therese died of scarlet fever. Alfonse resisted remarriage for several years, but the death of his only male heir, Arthur, in 1862, made him reconsider this decision.

His second wife was Marie, Countess of Lamberg (1833–1876), with whom he also had four children. Unfortunately, the second marriage did not last very long either, since Marie died at the age of only 42. But Alfons finally lived to see his longed-for heirs. The elder of them, Alfons Vladimír (1864–1935), later took over Boskovice. Besides taking care of the estate, Adolf also devoted himself to politics. From 1861 he sat in the Moravian Provincial Assembly in Brno and in the following year he also became a life member of the upper chamber of the Austrian Imperial Council. However, he did not see much sense in the exercise of these functions and seems to have been more comfortable with activities at a local level – in 1864–1876 he was mayor of Boskovice and in 1888 he even became its honorary citizen. Alfons died in Boskovice at the ripe age of 84 and was buried in the family tomb in Nečtiny (Preitenstein), which he had built himself.

Alexander was born on August 4, 1813 in Coburg as the third among his siblings. Like his brothers, he grew up in Coburg, where he befriended members of the most prominent European families. From a young age, however, he also felt a sense of belonging to the Austrian state and decided to serve in its army. His military career began in 1829 when he became a cadet in an infantry regiment. Over the next 20 years he rose to the rank of major general. He then entered the diplomatic service and became Austrian ambassador in St. Petersburg. However, he lasted only a year in this position and then returned to the army. At the end of the 1850s it started to become clear that if he really wanted to live up to his family duties, military service alone would not be sufficient. So he began to look around for a suitable bride. According to family correspondence, members of the Mensdorff-Pouilly family considered the mutual affection of both fiancés a necessary condition for marriage. However, Alexander seems to have given up on this requirement.

In 1857 he married Alexandrina of Dietrichstein (1824–1906), the future heiress of the large Mikulov (Nikolsburg) estate in South Moravia. The husband and wife had to find their way to each other, which was difficult at first, as they did not live together. Eventually, however, they became close and their marriage was happy. Four children were born into it, three of whom lived to adulthood – Marie (1858–1889), wife of Count Hugo Kálnoky (1844–1928), Hugo (1858–1920), heir to the estate and husband of the Russian noblewoman Olga Dolgorukova (1873–1946), and Klotylda (1867–1943), wife of Albert Apponyi (1846–1933).

In 1859 Alexander became lieutenant field marshal and two years later Governor in Lvov, where he also served as Commanding General for Galicia and Bukovina. One of the highlights of Alexander’s career was undoubtedly the year 1864, when he was appointed Austrian Foreign Minister. During his tenure, however, Austria lost the Austro-Prussian War, and Alexander was subsequently relieved from his post. At the end of his life, he served as Czech governor in Prague. It was also in Prague that he died on 14 February 1871 and was buried in the family tomb in Mikulov.

The castle in Mikulov today

The castle in Mikulov today

The youngest Arthur, like his brothers, was born in Coburg, on 19 August 1817. He too became an officer in the army and for many years served the Austrian Emperor. However, when it became clear that he would get no further than the rank of major, he decided to leave active service in 1852. Instead, he turned to business. He tried his luck in coal mining but failed. Unfortunately, the income from his lands did not cover his expenses, so he was forced to borrow frequently from his family, including Queen Victoria. Neither was he very successful in his personal life. In 1853 he married Magdalena Kremz (1835–1899), a low-born circus rider, whom he had fallen in love with. His brothers and other relatives strongly criticized him for this decision and never fully accepted Magdalena in their midst. However, they did not reject Arthur himself and continued to help him. Arthur later came to regret his choice, since Magdalena really was not a good match for him, and in 1882 they divorced. Near the end of his life, Arthur found himself a matching bride – Countess Bianca Adamovich de Csepin (1837–1912). After two years of marriage, Arthur died in Velenje, a town in what is now Slovenia.

Service in the army played an absolutely fundamental role in the lives of the four Mensdorff-Pouilly brothers. Along with their aristocratic origin, it enabled them to establish themselves socially and economically in Austrian society. The family’s marriage policy also helped them on their way to the top. It was thanks to his wife’s inheritance that Alphonse became a landowner. As for Alexander, although he himself did not participate in the running of the Mikulov estate, the profits from it allowed even him to lead an expensive life. His clerical career was rather a side effect of the military one, and his social status, abilities and character, which made him popular among the people, undoubtedly played a role in it.

Bibliography:

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Rodinné strategie šlechty. Mensdorffové-Pouilly v 19. století. Praha: Argo, 2007.

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Rod Mensdorff-Pouilly a boskovický velkostatek. In: Ott, Matěj, Markéta Malachová, and Roman Malach: Boskovice 1222–2022. Boskovice: město Boskovice ve spolupráci s Muzeem regionu Boskovicka, 2022.

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Šlechtic – Příklad Huga Mensdorffa-Pouilly. In: Fasora, Lukáš, Jiří Hanuš, and Jiří Malíř. Člověk na Moravě 19. století. Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury, 2008.

Brichtová, Dobromila: Zámek Mikulov. Mikulov: Regionální muzeum v Mikulově, 2015.

Brichtová, Dobromila: Pod tvými ochrannými křídly. Od loretánského kostela k hrobce Dietrichsteinů v Mikulově. Mikulov: Turistické informační centrum, 2014.

Steiner, Petr: Hrabě Hugo Kálnoky de Köröspatak (1844–1928). Život a osudy šlechtice na konci 19. století. Časopis Matice moravské 141/1, 2022.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.

At the end of the 18th century, this was not an unusual sight. On 27 July 1796 in a church in the South Bohemian town of Kdyně, the then thirty-seven-year-old Regional Commissioner Franz Merkl (1759–1829) and the eighteen-year-old daughter of an estate inspector Theresie Dalquen (1778–1868) stood side by side. Franz was not getting married for the first time, he was a widower, but apparently had no children from his first marriage. As a well-placed civil servant, he certainly made an interesting match for unmarried ladies and their parents. But the marriage of Franz and Therese was, after all, rather exceptional for its time. It produced ten children, all of whom lived to adulthood and most of whom died at a ripe old age. This was quite rare at a time when, on average, a quarter of the children born did not live to see their first birthday. Equally unusual was that nine out of the ten children were sons. Franz’s career also developed very promisingly, later he rose from a Regional Commissioner to Governor’s Councillor, and in 1811 he was knighted, a title which was subsequently also used by his sons. Franz died in Mladá Boleslav in 1829, his wife surviving him by almost 40 years.

Franz Merkl’s career was inextricably linked to the pre-March administrative system, in which Franz, the son of a Viennese tailor, achieved an extraordinary social rise. He was undoubtedly aware of the importance of a proper education in terms of social status, which was also reflected in the upbringing of his children. As many as four of his sons achieved important positions as senior civil servants, serving as District Administrators or District Captains. His fifth son advanced even further in his career, becoming the Land President of Silesia.

Like his father, the firstborn son Bernard (1797–1857), born on 29 June 1797 in Kout in Šumava, embarked on a successful career path by starting his career as a civil servant. At the age of 21, he started to work as a Trainee Official in the regional office in Mladá Boleslav and after 11 years he obtained the position of Supernumerary Regional Commissioner. Attaining this position provided him with sufficient means to look for a bride. On 16 August 1830 he married Agnes Römisch (1804–1855), daughter of the owner of the Malá Skála estate. Their marriage produced three children – the elder daughter and son unfortunately died in infancy, but the youngest, Jan Merkl (1847–1922), became chief engineer at the Vítkovice ironworks. In the following years Bernard rose up on the career ladder and achieved his first career peak in 1846 as a Regional Commissioner of Ist class. Unlike his father, who worked in various places, this phase of Bernard’s career was firmly tied to Mladá Boleslav. And it might well have remained so if it had not been for the revolution of 1848 and the associated changes in various spheres of life of the Austrian Monarchy. One of these changes consisted in the transformation of the political administration. In 1849, Bernard became a District Captain in Chotěboř, where after six years he reached the post of District Administrator. He died in office in 1857.

The second-born son of Franz Merkl and his wife Theresie was also named Franz (1799–1878). He was born in his father’s following place of work – the town of Slaný. We do not have much information about his life. He joined the army, where he attained the rank of captain, and died unmarried in Prague at the age of 79.

Their third son, Karel (1800–1870) was again born in Kout in Šumava. Like his brother Franz, he embarked on a career as a soldier and became a colonel in the Austrian army. Karel also did not marry and died in Prague in 1870.

After the birth of their first three children, the Merkl family moved again to Slaný, where on 11 December 1801 the twins Edmund and Heinrich were born. Not only did the boys survive their birth, which in itself was a small miracle, but in adulthood they both became senior civil servants like their father. Heinrich Merkl (1801–1874), after studying law at the University of Vienna and Prague, obtained a post as a Trainee Official in the town of Jičín. Like his father, he held several different offices, but twenty years later it was again in Jičín that he became a Regional Commissioner. He reached the peak of his career in 1855 as district chief in Hradec Králové. Unlike his father, however, he did not marry and died before his sixty-first birthday in Prague.

Unlike Heinrich, his brother Edmund (1801–1862) married no less than four times. At the age of 22 he joined the regional office in České Budějovice as a Trainee Official. He did not even wait to be promoted before getting married for the first time – in 1831 he married Antonie Stulíková (1806–1835), the daughter of an innkeeper. However, four years later, Edmund became widowed. More than six years after he got married a second time, in 1842, to Vilemína Křepinská (1823–1945), the daughter of a postmaster. But even his second marriage did not last very long, as Vilemína died after three years. This time Edmund did not mourn for too long and the very next year he married for the third time, Amalie Pazourková (1826–1851), the daughter of a “Justiziar” from Plzeň, i.e. an official with legal education. The third marriage lasted for five years, until Amalie’s death in 1851. Eight years later, Edmund entered into his last marriage. The bride, Matilda Křepinská (1828–1868) was not only 26 years younger than her groom, she was also the younger sister of Edmund’s second wife, Vilemína. It is also not without interest that another of the sisters, Klementina Křepinská (*1831), married Alois Josef Mascha (1816–1888), who also served first as a district chief and in the 1870s held the post of District Captain in Chrudim. Merkel’s fourth marriage lasted the longest – ten years. However, neither Matilda survived her husband, dying six years before him, so Edmund died a four-time widower.

Let us also look at the fate of Edmund’s other siblings. On 10 March 1804, the Merkls had their sixth child, their only daughter Katerina (1804–1824). Of all her siblings, she died at the youngest age, when she was only twenty, so she did not even have time to marry.

Her brother, August Merkl (1807–1883), was born on 14 May 1807 in another of his father’s places of work, the town of Mladá Boleslav. Like his father and some of his brothers, he embarked on a civil servant career, attaining the post of Land President in Silesia. He married Adelheid (1818–1882) from the noble family of von Sturm zu Hirschfeld. They married in what is now Kolomyja, Ukraine, which in the 19th century was part of the Habsburg monarchy along with the whole of Galicia. The marriage produced two children, who were already born in Lvov. Daughter Therese (1838–1880) married Josef von Mensshengen (1830–1891), a Silesian Governmental Councillor, and son Bohuslav (1835–1904) became a military officer. He eventually died in Hvar, Croatia. As for August himself, at the end of his life he first lived in Vienna, but died in Innsbruck.

The eighth son, Friedrich (1808–1886), was born in Mladá Boleslav on 29 June 1808. The army became his destiny, he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Military Cross of Merit for his achievements. He too never married and died in Prague in 1886.

It was also in Mladá Boleslav where a year later – exactly on 5 November 1809 – another son of the Merkls, Albrecht (1809–1860), was born. He attained the rank of colonel in the General staff, but unlike his other brothers, he managed to combine military service with family life. He married Karoline Baumgärtner (1820–1891) in Karlsruhe, Germany. Their daughter Matylda (1848–1937) married Karl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1838–1897), a historian who was professor at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, the son of the famous composer. Compared to his brothers Albrecht died quite young – he died in Prague at the age of fifty.

The last child the Merkls had was Wilhelm (1815–1892), born on 1 October 1815 in Mladá Boleslav. Wilhelm also chose a career as a civil servant and worked his way up to become a District Captain in Jasło, a town in the southeast of present-day Poland. In the 19th century, however, the town was under the administration of the Austrian Empire, along with the whole of Galicia. Wilhelm found a bride among the Polish nobility and in 1848 he married Josefina Gruszczynska (1825–1878). Their sons also achieved important positions within the Austrian administration. Wilhelm died in 1892.

The story of the Merkl family is very interesting both demographically and socially. Their unusually favourable mortality condition applied not only in childhood; five of Franz Merkl‘s nine sons died after they had reached the age of seventy, which was also unusual at that time. At the same time, mostly all of the Merkl siblings had successful professional careers. Interestingly, they only took two paths – either they became civil servants like their father or they joined the army. Although Franz Merkl had acquired a noble title, he did not possess a family fortune from which at least one of his sons could live. Therefore, his descendants had to provide for their own financial needs. The family history of the Merkls also shows the immense size of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th century. Looking at today’s map, it would appear that the brothers were active in four different countries – the Czech Republic, Austria, Poland and Ukraine – but in fact all the time they were on the territory of the Austrian Empire.