Wolfgang Achtner moved to New York where he settled and started a family.

Wolfgang Achtner was born on 19 December 1901 in Karlovy Vary. His father Karel Viktor (1863–1927) was a professor at a local grammar school and the son of a land school inspector Michael Achtner (1832–1877). Wolfgang's mother Olga (*1875) also descended from a well-situated family – her father Josef Fillén (1839–1889) owned a factory in the Karlín neighbourhood of Prague.

Early in 1926 Wolfgang set out on a journey across the ocean which originally was supposed to last only six months, but in the end lasted much longer. His ship set sail from Bremen on 27 February and after a 13-day voyage dropped anchor in New York. By that time, Wolfgang had already been an engineer.

It is not entirely clear whether he spent the whole of the next 22 years in the United States. What we may claim with certainty is that sometime during 1948 he married the twenty-four-year old Marion Hollister (*1924) from Massachusetts.

Even after many years, Wolfgang did not lose contact with Europe and in 1954, with his wife and a young son Wolfgang Michael (*1951), crossed the ocean again.

He did spend the rest of his life in America, however, and based on records from social security, this is also where he died in 1991. In Wolfgang's case, there is a chance that his descendants could still be living somewhere in New York.

What originally brought Wolfgang to the United States remains a mystery. It is not clear whether he really planned to stay for only six months, as he stated in official documents upon his arrival. Permanent migration often „happened“, without being planned in advance. Moreover, if the migrant married and started a family in his new home, the probability that he would return to his country of origin was even lower.

Wolfgang Achtner moved to New York where he settled and started a family.

Wolfgang Achtner was born on 19 December 1901 in Karlovy Vary. His father Karel Viktor (1863–1927) was a professor at a local grammar school and the son of a land school inspector Michael Achtner (1832–1877). Wolfgang's mother Olga (*1875) also descended from a well-situated family – her father Josef Fillén (1839–1889) owned a factory in the Karlín neighbourhood of Prague.

Early in 1926 Wolfgang set out on a journey across the ocean which originally was supposed to last only six months, but in the end lasted much longer. His ship set sail from Bremen on 27 February and after a 13-day voyage dropped anchor in New York. By that time, Wolfgang had already been an engineer.

It is not entirely clear whether he spent the whole of the next 22 years in the United States. What we may claim with certainty is that sometime during 1948 he married the twenty-four-year old Marion Hollister (*1924) from Massachusetts.

Even after many years, Wolfgang did not lose contact with Europe and in 1954, with his wife and a young son Wolfgang Michael (*1951), crossed the ocean again.

He did spend the rest of his life in America, however, and based on records from social security, this is also where he died in 1991. In Wolfgang's case, there is a chance that his descendants could still be living somewhere in New York.

What originally brought Wolfgang to the United States remains a mystery. It is not clear whether he really planned to stay for only six months, as he stated in official documents upon his arrival. Permanent migration often „happened“, without being planned in advance. Moreover, if the migrant married and started a family in his new home, the probability that he would return to his country of origin was even lower.

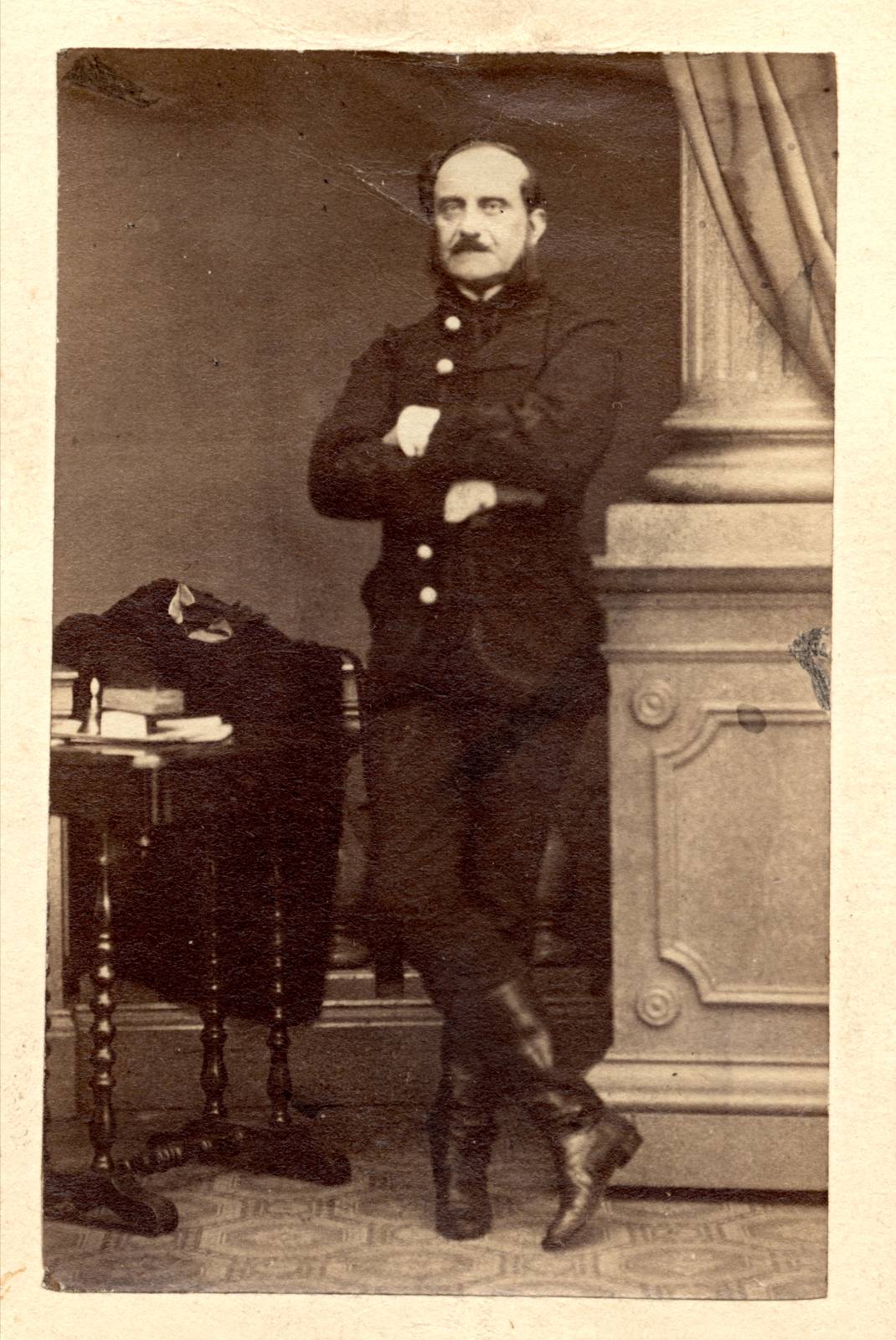

Count Manó (Emánuel) Péchy (1813–1889)

The Péchy family received the noble charter from Ferdinand I. at the beginning of the 16th century. The extended family held important positions in Sáros county, several of them were county commissioners (alispán), but later they also spread to other counties. The MP’s father József Péchy was a landowner in Abaúj-Torna county, and for his financial help in the Napoleonic Wars he was awarded the title of count in the early 19th century (1810). So when Emánuel / Manó Péchy was born in 1813 in the family castle in Boldogkőváralja, Abaúj county, the ink was barely dry on his father’s aristocratic rank.

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Péchy passed the bar exam in 1834, after studying law at the Academy of Law in Košice (Kassa). In the 1839–40 Diet he became a representative of Abaúj county, after having been vice- and then chief county notary for a short time. His loyal attitude in the Diet probably contributed to the fact that at the end of 1841 Archduke Joseph (1776–1847), the Palatine of Hungary, appointed him as the administrator of the Zemplén county, which was adjacent to Abaúj. However, Péchy’s early career was interrupted by the revolution of 1848.

In 1844 he married Baroness Zenaida Meskó (1828–1861), the younger daughter of Baron Jakab Meskó and Count Anna Fáy. The Meskó sisters were considered a very good party, because in the absence of a male heir, they inherited the entire family fortune. It seems that the older sister, Irén, was intended for Péchy first. We do not know the reason why this marriage failed, but the fact is that in 1843 Irén married count Henrik Zichy (1812–1892), while Péchy married the younger sister Zenaida a year later. His only brother Konstantin (1821–1866), who was an officer in the army, was married to Count Irma Forgách (1822–1872), also from an aristocratic family in the area.

Although conservative, Péchy did not take office during the years of neo-absolutism; he retired to his estate to wait for better times. Following the October Diploma (1860), the Hungarian counties were restored. Péchy was appointed as the Lord-Lieutenant of Abaúj county and the city of Košice (Kassa). The following year, however, he resigned, as did most of the Lord-Lieutenants. The new Chancellor count Herman Zichy (1814–1892) was the brother of Péchy’s brother-in-law Henrik Zichy.

In 1865, as a prelude to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, new Lord-Lieutenants were partly appointed and parlty reinstated, including Péchy, as the head of Abaúj county and Košice. However, his career took a new direction after the Compromise. At that time, he was appointed Royal Commissioner for Transylvania, with the task of overseeing the integration of Transylvania, advising the Hungarian government and reducing ethnic tensions. His appointment was initiated by the Prime Minister, Gyula Andrássy (1823–1890), with whom they had known each other since Péchy was the county administrator of Zemplén County.

After the abolition of the royal commissioner’s office (1872), Péchy’s ties with Transylvania loosened, if not completely disappeared. From 1872 he was a member of the Parliament of Cluj (Kolozsvár) for three terms. Subsequently, in 1881, he was elected in Košice, where he began his political career. His name came up a few times in political combinations: as Minister of the Interior and, in 1879, as Minister of Finance. But no further political role awaited him. The elderly Péchy was a member of the upper house of parliament.

In his private life he suffered many adversities. Several of his children died in infancy and his only son was killed in an accident when he was ten. His wife never recovered from this loss, and died in 1861 after a long illness. He did not remarry after his wife’s death, although there are several hints of his gallant adventures. Perhaps the most controversial was his affair with a young actress in Košice, Lujza Nagy (1843–1911). His only daughter Jaqueline Péchy (1846–1915) was brought up by his brother-in-law Henrik Zichy in Moson County until she married Henrik’s younger brother Rudolf (1833–1893) – stepson of the famous Hungarian politician István Széchenyi (1791–1860) – in 1864. Jaqueline had seven children, but she was unable to see her younger children because she became blind at a young age.

Manó Péchy even lived to see one of his grandchildren, Eleonóra Zichy (1867–1945), marry the son of the former Prime Minister and later Foreign Minister of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Gyula Andrássy, Tivadar (1857–1905) (and after his death to his other son Gyula Andrássy Jr., 1860–1929). Katinka Andrássy (1892–1985), the great-granddaughter of Manó Péchy, one of the couple’s daughters, became famous as the “Red Countess”. She was the wife of Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955), the Prime Minister and later President of the Republic who came to power in 1918 after the so-called Aster Revolution.

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Manó Péchy died in the summer of 1889 in Boldogkőváralján, in his family castle.

Boldogkőváralján residence Boldogkőváralján castle

Bibliography

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Aristokrat v službách štátu. Gróf Emanuel Péchy, Bratislava, Kalligram, 2006.

Judit Pál, Unió vagy „unificáltatás”? Erdély uniója és a királyi biztos működése (1867–1872) (Union or "unification"? The Union of Transylvania and the functioning of the Royal Commissioner). Kolozsvár, Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2010.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Emanuel Péchy ako župan Abova a Košíc. In: Historica Carpatica. Zborník Východoslovenského Múzea v Košíciach 35 (2004). Vydalo Východoslovenské múzeum v Košiciach, 2004, pp. 55–72.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Štyri stretnutia a dve kariéry (gróf Gyula Andrássy a gróf Emanuel Péchy). In: Acta Historica Historica Neosolensia, tomus 9, Banská Bystrica, Katedra histórie FHV Univerzity Mateja Bela, 2006, pp. 65–80.

Judit Pál, Péchy Manó – a „mintahivatalnok” (Manó Péchy the „model official”). Erdélyi Múzeum. LXIX. (2007) no. 1–2, pp. 33–61.

Judit Pál – Roman Holec, Gróf Emanuel Péchy ako kráľovský komisár Sedmohradska (1867–1872). In: Historické štúdie. roč. 45 (Bratislava, 2007), pp. 169–203.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Dvaja vysokí štátni úradníci – dva integračné pokusy – dve „imperiálne kariéry“? (knieža Karl Schwarzenberg a gróf Emanuel Péchy v Sedmohradsku). Historický časopis, vol. 62 (2014) nr. 3. pp. 447−470.

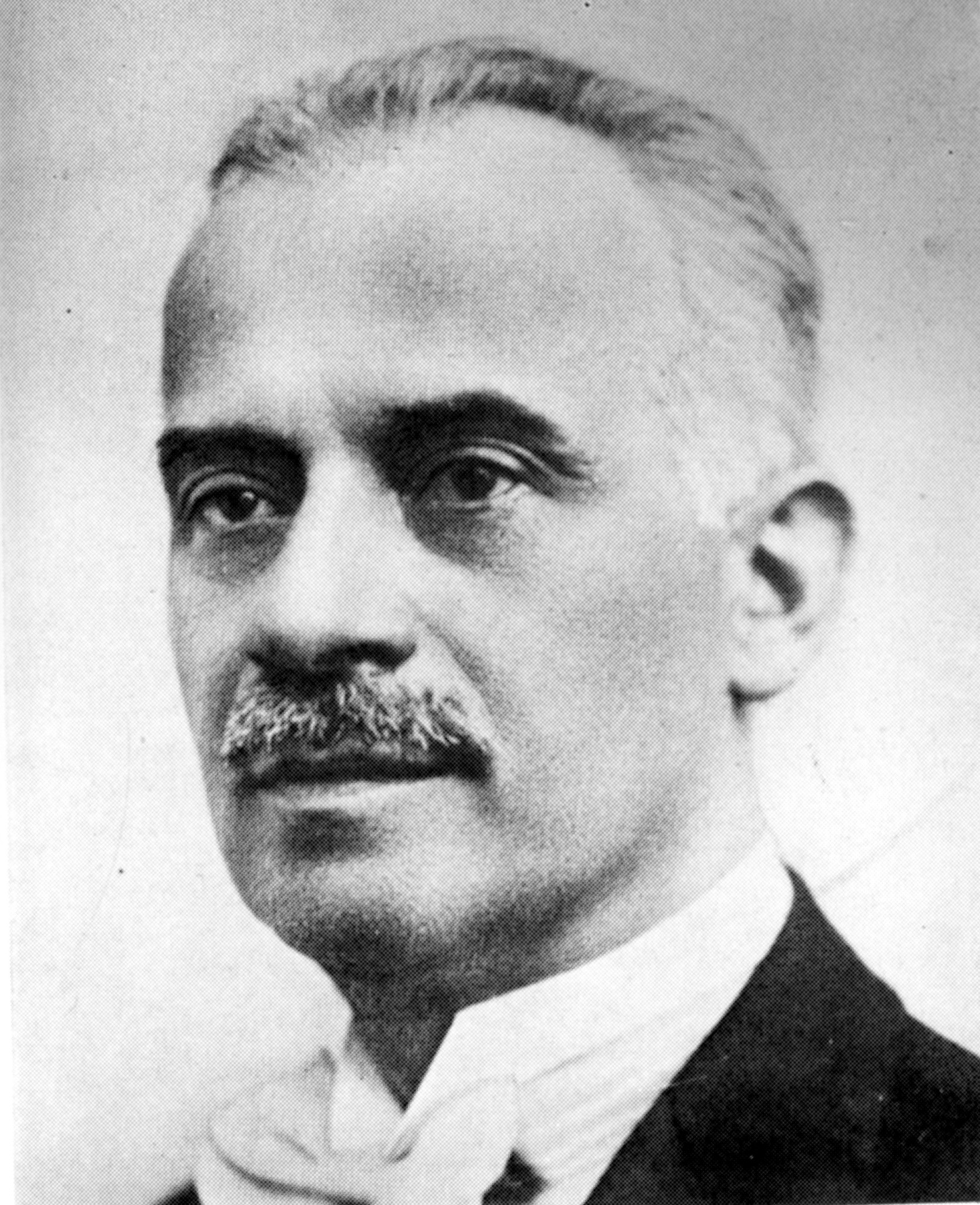

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu (1876‒1942) ‒ a politician, writer and publicist

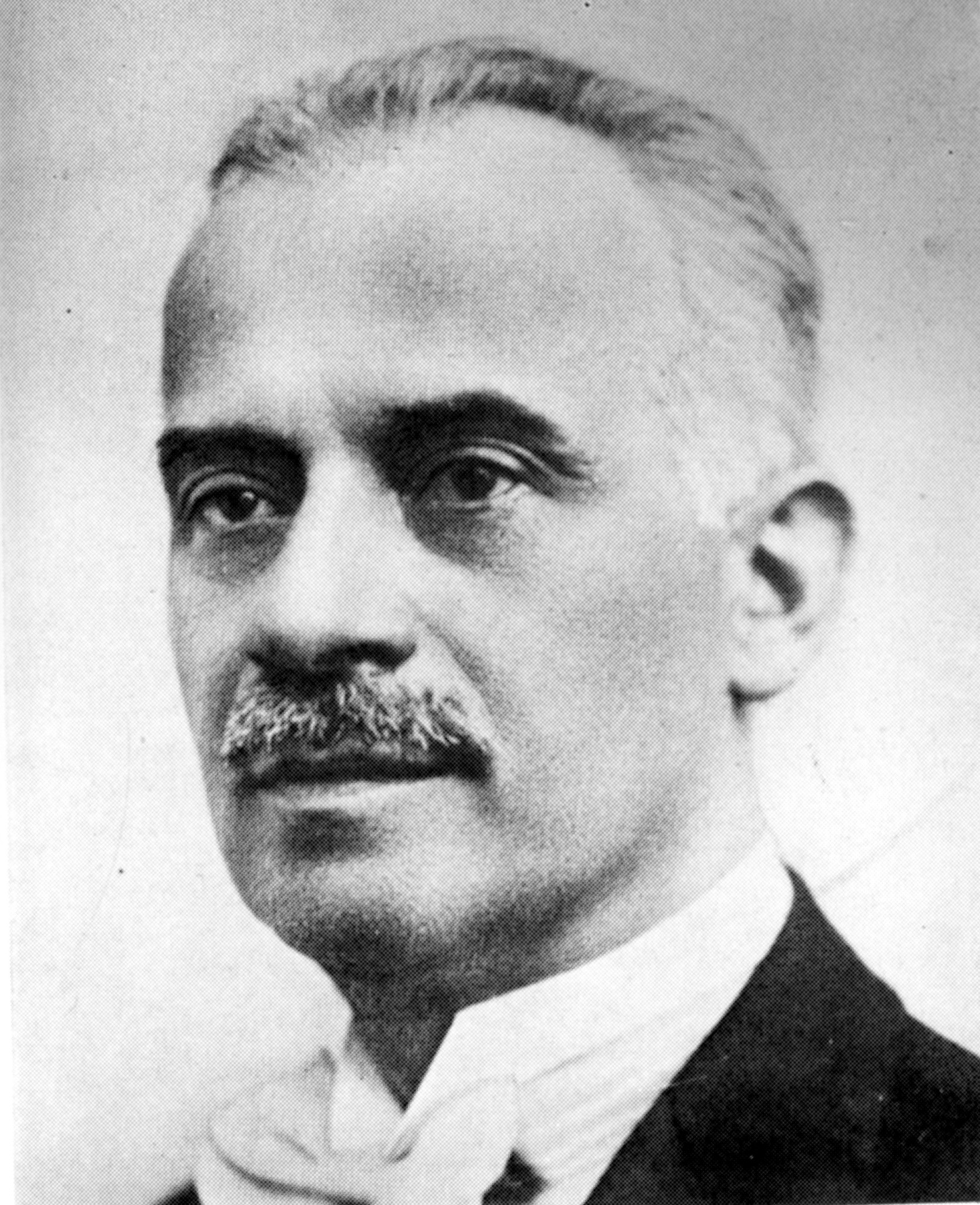

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu was born on 1 February 1876 in the village Bilbor, Ciuc County. His father, Ioan Tăslăuanu (?–1927), was a priest, and his mother, Anisia Stan (1859–1933), came from a peasant family. Tăslăuanu attended secondary school in Năsăud (1889), Brașov (1890 –1892) and Blaj (1892–1895). Due to disagreements with his father about his career, as his father wanted him to become a priest, Tăslăuanu left for Bucharest in the Old Kingdom of Romania, where he worked as a teacher at a private school. At the same time, he continued his studies at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (1898–1902), supporting himself by teaching.

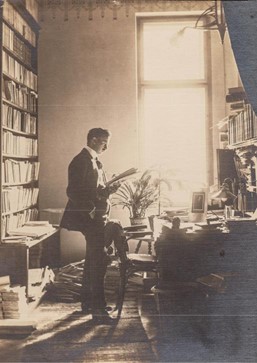

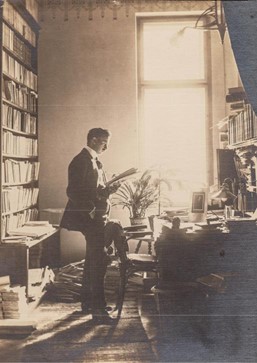

Taslauanu in his office

Taslauanu in his office

In 1902, on the recommendation of Ion Bianu (1856–1935), one of his professors and director of the Romanian Academy Library, he was appointed secretary of the Romanian Consulate General in Budapest. There, in addition to his duties, Tăslăuanu became involved with the magazine “Luceafărul”, first as a proofreader and later as an editor. Published successively in Budapest (1902 –1906), Sibiu (1906–1916) and Bucharest (1919–1920), “Luceafărul” promoted national culture and the political unity of the Romanians in Transylvania.

In his private life, in 1906, Tăslăuanu married Adelina Olteanu-Maior from Sibiu (1877–1910), who came from an old and prestigious family of intellectuals. She was also a writer and author of several books of children's stories. Godparents to their marriage were the family of Constantin Argetoianu (1871–1955), one of the most influential Romanian politicians of the inter-war period.

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina with Octavian Taslauanu 1907

After the marriage, Tăslăuanu settled in Sibiu, where he served (until 1914) as an administrative secretary of the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People (ASTRA) in Sibiu. ASTRA was the most important and influential cultural and political association of Romanians in Transylvania.

From 1907, Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu took over the direction of the journal “Transilvania” (published by ASTRA), first as an editor and later as a director, transforming it into a true reflection of Romanian culture and science. His work was particularly fruitful, especially through the reorganisation of the ASTRA Popular Library, which included the monthly publication of a new volume of this collection, together with an annual calendar distributed to all the members of the branch, reaching almost every locality in Transylvania. Between 1911 and 1914, under his supervision, 49 issues within this collection were published, including various history books and anthologies of classical authors. The print run of a single issue reached 15,000 copies in 1912, with 11,861 sent to subscribers. However, this period was marked by the death of Adelina Tăslăuanu in 1910 from heart disease.

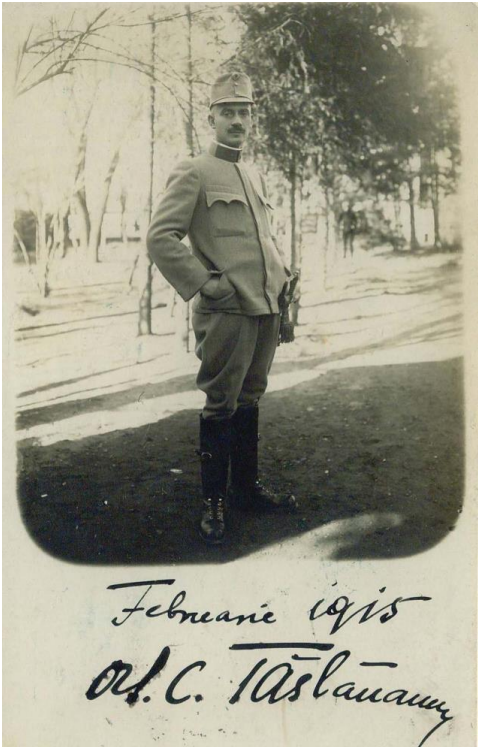

In 1914, Tăslăuanu was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army and sent to the front in Galicia, but he deserted to Romania and volunteered for the Romanian army, where he served in intelligence throughout the war. He became a Romanian citizen in July 1917 and was promoted to lieutenant and later captain.

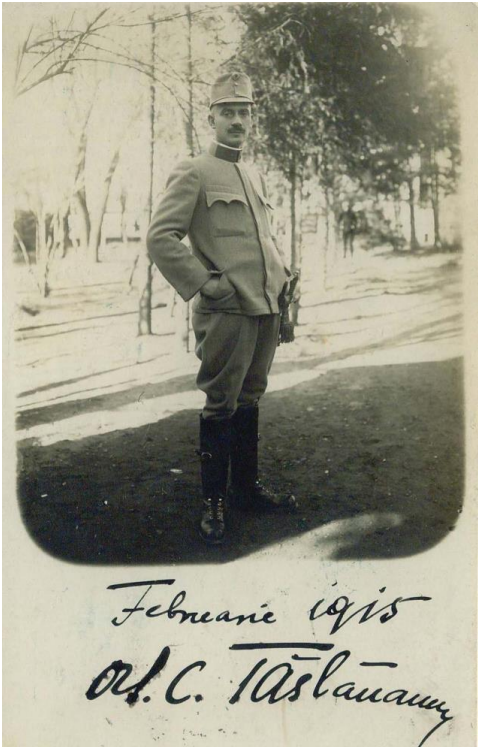

Taslauanu as an officer

Taslauanu as an officer

In 1918, Tăslăuanu married Fatma Alisa Sturdza (1893–1964), whom he had met as a nurse at the front. She came from an old aristocratic family of politicians and large landowners. Tăslăuanu had two children: Ioan Radu (born 1920), who died at the age of one, and Dafina (1921–2000). Dafina's godfather was the Primate Metropolitan of Romania, Miron Cristea (1868–1939).

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu also had a remarkable political career. In the parliamentary elections of November 1919, he was elected deputy of Tulgheș, standing for the People's League. In the government led by Alexandru Averescu (1859–1938), he served as Minister of Trade and Industry (13 March – 16 November 1920) and Minister of Public Works (16 November 1920 – 1 January 1921). In these roles, he initiated a number of important laws and reforms for the reorganisation of the national economy in the post-World War I period. His achievements include the establishment of the explosives factory in Făgăraș, the nationalisation of the Reșița factories, the organisation of the oil industry through the creation of the Romanian Oil Industry, the drafting of laws for the monopolisation of the oil trade and the organisation of the grain trade, the founding of the Polytechnic University of Timișoara and the securing of funds for the construction of the Commercial Academy in Bucharest. Between 1926 and 1927 he was senator for Mureș, where he proposed the participation of Romanian parliamentarians in the first Pan-European Congress in Vienna.

Octavian Tăslăuanu died in Bucharest on 22 October 1942. His career is remarkable, considering that he rose from the position of a rural priest's son to that of a parliamentarian and minister. He achieved this primarily through personal merit, but also by successfully building social connections with influential families, first through his marriage to Adelina and later to Fatma. Unlike him, his brothers Petru Tăslăuanu (1880–1957) and Cornel Tăslăuanu (1889–1974) did not experience such a significant social rise, although they were more than just peasants and had successful careers. Petru Tăslăuanu was a teacher and the headmaster of the primary school in Bilbor, while Cornel Tăslăuanu was a craftsman who eventually became the mayor of their native village, Bilbor.

References :

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu, Spovedanii, Ediție îngrijită de George-Bogdan Tofan, prefață de Filip-Lucian Iorga, Editura Mega, 2023.

Cornelia Luminița Radu, Revista Luceafărul, în Revista Română de Istorie a Cărții; Bucharest Iss. 3/4, (2006/2007): 40–46, 304–305, 317–318.

The source for pictures: George-Bogdan Tofan, The “Octavian C. Tăslăuanu” Foundation.

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu (1876‒1942) ‒ a politician, writer and publicist

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu was born on 1 February 1876 in the village Bilbor, Ciuc County. His father, Ioan Tăslăuanu (?–1927), was a priest, and his mother, Anisia Stan (1859–1933), came from a peasant family. Tăslăuanu attended secondary school in Năsăud (1889), Brașov (1890 –1892) and Blaj (1892–1895). Due to disagreements with his father about his career, as his father wanted him to become a priest, Tăslăuanu left for Bucharest in the Old Kingdom of Romania, where he worked as a teacher at a private school. At the same time, he continued his studies at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (1898–1902), supporting himself by teaching.

Taslauanu in his office

Taslauanu in his office

In 1902, on the recommendation of Ion Bianu (1856–1935), one of his professors and director of the Romanian Academy Library, he was appointed secretary of the Romanian Consulate General in Budapest. There, in addition to his duties, Tăslăuanu became involved with the magazine “Luceafărul”, first as a proofreader and later as an editor. Published successively in Budapest (1902 –1906), Sibiu (1906–1916) and Bucharest (1919–1920), “Luceafărul” promoted national culture and the political unity of the Romanians in Transylvania.

In his private life, in 1906, Tăslăuanu married Adelina Olteanu-Maior from Sibiu (1877–1910), who came from an old and prestigious family of intellectuals. She was also a writer and author of several books of children's stories. Godparents to their marriage were the family of Constantin Argetoianu (1871–1955), one of the most influential Romanian politicians of the inter-war period.

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina with Octavian Taslauanu 1907

After the marriage, Tăslăuanu settled in Sibiu, where he served (until 1914) as an administrative secretary of the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People (ASTRA) in Sibiu. ASTRA was the most important and influential cultural and political association of Romanians in Transylvania.

From 1907, Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu took over the direction of the journal “Transilvania” (published by ASTRA), first as an editor and later as a director, transforming it into a true reflection of Romanian culture and science. His work was particularly fruitful, especially through the reorganisation of the ASTRA Popular Library, which included the monthly publication of a new volume of this collection, together with an annual calendar distributed to all the members of the branch, reaching almost every locality in Transylvania. Between 1911 and 1914, under his supervision, 49 issues within this collection were published, including various history books and anthologies of classical authors. The print run of a single issue reached 15,000 copies in 1912, with 11,861 sent to subscribers. However, this period was marked by the death of Adelina Tăslăuanu in 1910 from heart disease.

In 1914, Tăslăuanu was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army and sent to the front in Galicia, but he deserted to Romania and volunteered for the Romanian army, where he served in intelligence throughout the war. He became a Romanian citizen in July 1917 and was promoted to lieutenant and later captain.

Taslauanu as an officer

Taslauanu as an officer

In 1918, Tăslăuanu married Fatma Alisa Sturdza (1893–1964), whom he had met as a nurse at the front. She came from an old aristocratic family of politicians and large landowners. Tăslăuanu had two children: Ioan Radu (born 1920), who died at the age of one, and Dafina (1921–2000). Dafina's godfather was the Primate Metropolitan of Romania, Miron Cristea (1868–1939).

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu also had a remarkable political career. In the parliamentary elections of November 1919, he was elected deputy of Tulgheș, standing for the People's League. In the government led by Alexandru Averescu (1859–1938), he served as Minister of Trade and Industry (13 March – 16 November 1920) and Minister of Public Works (16 November 1920 – 1 January 1921). In these roles, he initiated a number of important laws and reforms for the reorganisation of the national economy in the post-World War I period. His achievements include the establishment of the explosives factory in Făgăraș, the nationalisation of the Reșița factories, the organisation of the oil industry through the creation of the Romanian Oil Industry, the drafting of laws for the monopolisation of the oil trade and the organisation of the grain trade, the founding of the Polytechnic University of Timișoara and the securing of funds for the construction of the Commercial Academy in Bucharest. Between 1926 and 1927 he was senator for Mureș, where he proposed the participation of Romanian parliamentarians in the first Pan-European Congress in Vienna.

Octavian Tăslăuanu died in Bucharest on 22 October 1942. His career is remarkable, considering that he rose from the position of a rural priest's son to that of a parliamentarian and minister. He achieved this primarily through personal merit, but also by successfully building social connections with influential families, first through his marriage to Adelina and later to Fatma. Unlike him, his brothers Petru Tăslăuanu (1880–1957) and Cornel Tăslăuanu (1889–1974) did not experience such a significant social rise, although they were more than just peasants and had successful careers. Petru Tăslăuanu was a teacher and the headmaster of the primary school in Bilbor, while Cornel Tăslăuanu was a craftsman who eventually became the mayor of their native village, Bilbor.

References :

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu, Spovedanii, Ediție îngrijită de George-Bogdan Tofan, prefață de Filip-Lucian Iorga, Editura Mega, 2023.

Cornelia Luminița Radu, Revista Luceafărul, în Revista Română de Istorie a Cărții; Bucharest Iss. 3/4, (2006/2007): 40–46, 304–305, 317–318.

The source for pictures: George-Bogdan Tofan, The “Octavian C. Tăslăuanu” Foundation.