Though well-known in Transylvania during his time, Petru Meteș is almost unknown today, unlike his cousin, the historian Ștefan Meteș (1887–1977), or one of his sons, Mircea. Petru’s parents, Simion and Maria Meteș, were peasants from Geomal / Diomal in Alba de Jos / Alsó-Fehér County. They had at least six children who survived childhood: Petru (born in 1883, according to other sources: 1884 or 1886), Nistor (1893–1954), Octavian (?–1943), Iuliana (born ca. 1898), Cornelia (born ca. 1899), and Ioan (born ca. 1901). Simion and Maria were wealthy enough to send Petru and Nistor to study at the Hungarian-language Bethlen College of Aiud/ Nagyenyed.

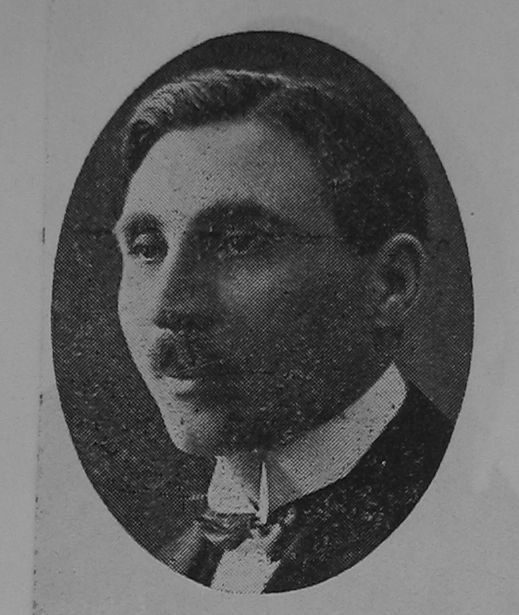

Petru Meteș, prefect of Cojocna (Cluj) county, Cosînzeana, VI, no. 1, 1922, p. 22 (https://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/1506)

Petru Meteș, prefect of Cojocna (Cluj) county, Cosînzeana, VI, no. 1, 1922, p. 22 (https://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/1506)

Ștefan Meteș, historian, MP, and member of the Iorga Cabinet as undersecretary (1931–1932), Anuarul parlamentar, 1931, Bucharest, 1932.

A studious pupil, Petru graduated from secondary school at Bethlen College. He continued his studies at the Franz Joseph University of Cluj / Kolozsvár, where he obtained a degree in Law and a PhD in Legal Science (1908). He did his law internship in Aiud, in the law office of the Hungarian lawyer Pál Szász, the son of József Szász, the főispan (prefect) of Alsó-Fehér County from 1910 to 1917. In 1910, Petru helped Pál Szász to be elected as a deputy in the constituency of Ighiu / Magyarigen – of which Geomal was a part – and whose population was predominantly Romanian. His close relationship with the Szász family helped him to be appointed honorary sheriff in 1910 (tiszteletbeli szolgabiró) and elected as a member of Alsó-Fehér County Congregation “on the Hungarian list” (i.e., on the governing party’s list). Furthermore, in June 1911, P. Meteș was admitted to the Cluj Bar as a lawyer in Aiud.

Město Kluž/ Kolozsvár, pohlednice

Město Kluž/ Kolozsvár, pohlednice

Alongside his connections with the Hungarian milieu, Petru Meteș also integrated into the Romanian society of the time. This seems to have been due to a large degree to his first wife, Iustina Maria Filipan (born ca. 1891–1892, in Bistrița / Beszterce), the daughter of a physician in the district of Năsăud / Naszód. In addition, he joined the local branch of the most important Romanian Association (ASTRA), and was also involved in helping the Orthodox Church.

Everything changed in 1914. Petru was sent to the front line and taken captive by the Russians. In the summer of 1917, he was already a member of the Transylvanian and Bukovinian Volunteer Corps, created within the Romanian Army and made up of Romanian refugees from the Habsburg Monarchy and prisoners of war from the Russian camps. Captain Petru Meteș fought in Moldavia in the summer of 1917 and was later dispatched to Odessa, probably to ensure the security of Romanian refugees and dignitaries. The Bolsheviks under Christian Rakovsky (1873– 1941) imprisoned him there for a short period. Following his liberation, he was hired as one of the three secretaries of the Technical Advisory Board of the Justice Ministry in Chişinău, in Bessarabia, recently integrated into Romania. Following the dissolution of Austria-Hungary and after the Romanians took over local and regional power, he returned to Transylvania where he was appointed as First President of the Dumbrăveni / Erzsébetváros Court of Law and soon transferred to a similar position to the more important Court of Law in Brașov / Kronstadt.

On 15 April 1920, judge Meteș was dispatched by the Ruling Council to fill in the office of prefect for Alba de Jos County. Six months later, Petru Meteș was transferred by the Averescu government and appointed Cojocna (Cluj) County prefect. On 1 January 1921, he was appointed full prefect, which implicitly meant his political involvement within the governing party (the People’s Party), which lacked leaders and members in Transylvania. Through this position, which gave him greater public visibility and enabled him to create a support network, Petru Meteș seems to have tried to find an entryway into politics. He succeeded in keeping the rank of prefect under the brief government of Take Ionescu (December 1921–January 1922) and in the first year of Ion I.C. Brătianu Cabinet. In February 1923, he chose to run for the Chamber of Deputies in the constituency of Ighiu in Alba County as the governmental (National Liberal Party) candidate. The opposition press fiercely attacked his candidacy, mentioning his “anti-Romanian” deeds before 1914. With the help of the local authorities, Petru Meteș won the elections. He served as deputy between 1923 and 1926.

Regarding his personal life, the marriage with Iustina broke up in the mid-1920s. Petru Meteș’s second wife was Victoria Octavia Crișan (born in 1903), the sister of Eugenia, the wife of his brother Nistor. Petru had two children from his first marriage, Mircea Virgil (born in 1912) and Ofelia, nicknamed Lili (born in 1915), and two from his second one, Petre (born in 1927) and Doina (1929).

Although he did not hold any political offices at the national level after 1926, Petru Meteș remained a prominent figure of the Transylvanian Romanian elite due not only to his intense career as a lawyer, but also to his involvement in a Veterans movement and his work in the management committees of various forums of the Transylvanian Orthodox Church. He died in Cluj in January 1946.

Mircea Meteș followed his father’s example: holding a bachelor’s degree and a PhD in Law, he became a lawyer. In 1938, he married Olivia (1913–2001), the daughter of Adam Lula, an Orthodox priest, and the niece of Petru Groza (1884–1958), the Communist choice, in March 1945 for the role of Prime Minister. His relationship with Groza was the leading cause of his career after 1945. Mircea Meteș was hired as head of the Prime Minister’s Secretary Office in 1946. Furthermore, he was admitted to the Foreign Service and soon appointed member of the Romanian mission to Washington. Recalled to Bucharest in 1948, he chose not to return to his homeland and became an opponent of the Romanian government. As a result, his brother and sisters came to be in the cross hairs of the State Security and were under surveillance for a long time.

Bibliography:

The Archives of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives: files regarding Petru Meteș and his children (Mircea Meteș, Ofelia Zehan, Petru Meteș and Doina Păstrav), folders no.: FI 94683, FI 139103, I 558274, I 574868, SIE 0007226.

Ioan Ciupea, Virgiliu Țârău, Liberali clujeni. Destine în marea istorie, vol. 2. Medalioane, Mega, Cluj-Napoca, 2007, pp. 241-242.

Zoltán Györke, “Prefecții județului Cluj: analiză prosopografică”, in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie „George Barițiu” din Cluj-Napoca. Series Historica, LI, 2012, pp. 305–308. (https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=23237)

Paul Nistor, “Comrade Mircea Meteș: the first communist of the Romanian Legation in Washington (1946-1948)”, in Adrian Vițălaru, Ionuț Nistor, Adrian-Bogdan Ceobanu (eds.), Romanian Diplomacy in the 20th Century. Biographies, Institutional Pathways, International Challenges, Peter Lang, Berlin, 2021, pp. 330-341.

The Rauca-Răuceanu brothers: a mayor and a prefect in the Trei Scaune County in the 1920s

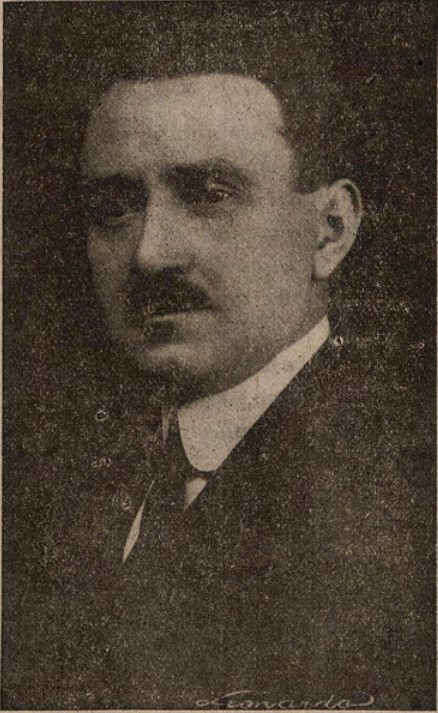

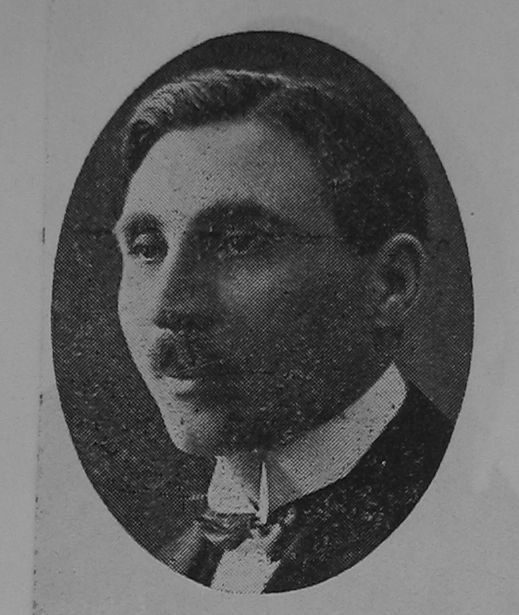

Isidor Rauca Rauceanu primar - Figuri Politice 1924

The surname Rauca/Róka-Răuceanu was easily recognized during the interwar period among the population of the Trei-Scaune (in Hungarian: Háromszék) County, in the so-called Székely Land, thanks to the brothers Vi(n)cențiu and Isidor (sometimes also spelled Izidor). They were members of the local Romanian-speaking political elite in a county with a majority Hungarian population. Their parents were Elie Răuceanu (?–1924), of Orthodox confession, and Rafira, born Iacob. Besides the two brothers, they had at least one daughter, Ana, who married Cucu.

For an extended period, Elie Răuceanu served as a teacher in Hăghig/Hídvég (Trei Scaune County), a village about approximately equidistant (24 km) from the county seat, Sfântu Gheorghe/Sepsiszentgyörgy, and the major city of Brașov/Kronstadt. In the early 20th century, he held a teaching position at a state school in Tömörkény (Csongrád County) in Hungary. During this tenure, he filed a lawsuit against the Ministry of Education because his name was changed from Răuceanu to Róka (meaning fox in Hungarian) without his consent. This legal action brought him public attention as he went unpaid for several months. Later, his sons Romanianized the Hungarian family name to Rauca, resulting in their surname becoming Rauca-Răuceanu.

Vicențiu was born in December 1889 in Hăghig, while Isidor in May 1891 in Măieruș/Nussbach (Brașov County), a village near Hăghig. Both brothers followed a similar educational trajectory. Vicențiu graduated from the Law Faculty in Budapest (1908–1912) and took his doctorate in January 1914. The younger brother commenced his law studies in Budapest (1911/1912) and continued them in Cluj/Kolozsvár, completing them in 1919. A decade later, Isidor defended his doctorate in Juridical Science at the University of Cluj.

The outbreak of World War I was challenging for the Răuceanu family. While the father was known as a Romanian nationalist, his sons appeared to integrate into Hungarian society. Elie Rauca was considered a Romanian sympathizer in 1916 and interned in a camp. Both brothers were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army. Though the circumstances remain unclear, in a 1972 letter to a local newspaper, Isidor mentioned his status as a war invalid. From this and other sources, it is known that he was appointed as an assessor to the Odorhei/Udvarhely Court of Law in 1915 and briefly served as a County Commissioner (alispán) of Odorhei County in 1916. Vicențiu’s military service details are not fully documented either. He was enlisted in 1914 or 1915, completing his training in Brasov, and was deployed to the front in autumn 1915, attaining the rank of lieutenant by the war’s end.

After the integration of Transylvania into Romania, new opportunities arose for the Răuceanu family. In early 1919, Vicențiu led the Romanian guards in Trei Scaune County. Shortly after that, he was appointed high sheriff (in Hungarian: főszolgabíró; in Romanian: prim-pretor) of the Sfântu Gheorghe District. In 1920, he assumed the role of jurisconsult of Trei Scaune County, only to return to his previous position as high sheriff in the following year (April–July 1921). Isidor also held significant public responsibilities at the local level, serving as a member of various county commissions related to land reform, among other matters. At least during 1919–1920, they aligned themselves with the Romanian National Party and advocated for provincial autonomy. By 1921, however, the brothers shifted their allegiance to the National Liberal Party, originally from the Old Kingdom, and took leadership roles in local party organizations.

Kossuth Lajos Street in Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, postcard

The rise of the Răuceanu family in popularity and local influence coincided with the formation of a Liberal government in January 1922 under the leadership of Ion I.C. Brătianu (1864–1927). Alexandru Iteanu (1869–1928), also from Hăghig, who had pursued studies in Pharmacy in Bucharest and established himself in the Old Kingdom, owning pharmacies and a highly esteemed laboratory named “Flora,” significantly contributed to their growing influence within the National Liberal Party. Despite residing mainly in Bucharest, Iteanu was tasked with establishing a robust liberal organization in Trei Scaune County. For this endeavour, he found reliable allies in the Răuceanu brothers, who possessed deeper connections within local networks. Iteanu assumed the position of prefect of Trei Scaune County in January 1922 but resigned after just two months to become a deputy.

Trei Scaune County Prefecture building (currently Covasna County Library), Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, postcard

Isidor was appointed mayor of Sfântu Gheorghe, the county seat, an office he held from April 1922 to April 1926 and again from June 1927 to June 1928. Two months later, on 22 June 1922, Vicențiu became prefect of Trei Scaune County. Today, local discussions often revolve around the accomplishments of Mayor “Isidor Rauca,” such as the installation of sewerage systems and asphalting of the streets, the modernization of the central park, where he erected a pavilion that stands to this day, and the restoration of several buildings. During his tenure, the prefect Răuceanu boasted various achievements, including constructing 40 schools and renovating dozens of others.

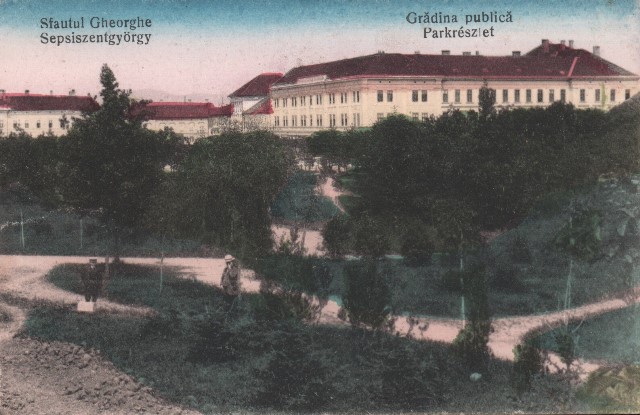

Elisabeth Park (“Central Park”) of Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, whose development began in 1880, but to which Mayor Isidor Răuceanu also contributed, postcard

The opposition press, in particular, levied numerous accusations of corruption and abuse of power against the two brothers. Vicențiu faced allegations of misappropriating funds from the illegal sale of 150 wagons of corn intended for distribution to the population, abuse of office for personal gain, and intimidation of magistrates. By the end of 1925, he had become the subject of several interpellations in the Romanian Assembly of Deputies, consistently defended by his political patron, Alexandru Iteanu. In April 1926, shortly after the Ion I.C. Brătianu government resigned, Isidor was suspended by a decision of the Sfântu Gheorghe municipal council. He faced accusations of forgery of public documents, embezzlement of public funds, and abuse of office, with this decision being confirmed by the Ministry of the Interior. Isidor Răuceanu received the right to be reinstated in June 1927, only to be suspended again a year later. Meanwhile, Vicențiu stood trial in 1927 for the sale of corn but was acquitted. In 1928, facing the threat of losing his parliamentary immunity, Vicențiu defended himself by accusing the People's Party government (March 1927 – June 1928) of framing him in nearly 20 criminal trials.

The brothers suffered a significant setback when their friendship with Alexandru Iteanu soured. “Curentul,” a Bucharest newspaper, attributed the rift to Mayor Răuceanu's refusal to marry Iteanu’s sister-in-law. In June 1928, despite Vicențiu being an MP, both brothers were expelled from the county organization of the National Liberal Party. Although Alexandru Iteanu passed away in October 1928, the brothers joined a small liberal party ruled by Gheorghe Brătianu (1898–1953), the son of Ion I.C. Brătianu. Since June 1931, with the exception of the 1932 elections, Vicențiu, who also served as the head of the county organization, continuously ran for Parliament on the list of the National Liberal Party – Gheorghe Brătianu, in Trei Scaune County but failed to secure election. On the other hand, Isidor was a parliamentary candidate only in the 1932 elections, representing this party and replacing his brother.

Vicențiu (from 1926) and Isidor (after 1929) pursued careers in law. During the 1920s, Vicențiu was the director of the Sfântu Gheorghe branch of the General Bank of Romania and sat on the member of the Board of Directors of the Credit Bank – Sfântu Gheorghe. Later, from 1936 onward, he assumed the directorship of this institution. He also headed the county's ASTRA branch and was actively involved in the Orthodox Church activities. Both brothers made donations to the church in Hăghig, their hometown. They jointly established the first local political periodical in Trei Scaune County, titled “La Noi,” which was published weekly between 1932 and 1934.

Despite presenting themselves to higher authorities in Bucharest as nationalists, the Răuceanu brothers maintained cordial relations with the Hungarian elites. Furthermore, though it might have been perceived as a flaw for a member of the leadership of a Romanian party, Vicențiu was married to Erzsébet/Elisabeta Sütő, an ethnic Hungarian woman. However, after 1948, despite no evidence to support it, a Securitate (Romanian Secret Police under the communist regime) report labelled Vicențiu, still married to Erzsébet, as a chauvinist. Almost all their real estate was nationalized by the communist regime.

Vicențiu died on 2 April 1954 in Sfântu Gheorghe, and Isidor died in Săcele (Brașov County) on 27 October 1975. Neither of the brothers had children.

At the beginning of 1972, the newspaper “Cuvântul Nou,” published by the county organization of the Romanian Communist Party, featured an article discussing the city of Sfântu Gheorghe in the 1920s, focusing particularly on the alleged wrongdoings of Mayor “Isidor Rauca.” With nothing left to lose and considering the less severe repression against former enemies of the Communist Romania, Isidor Rauca-Rauceanu sent a letter to the newspaper. This text, published in the newspaper, contains subtle irony and a desire to convey to both the public and future generations the administrative achievements of the Răuceanu brothers, along with other benevolent actions such as providing financial support for four pupils (two Romanians and two Hungarians) to pursue high school education, and the establishment of the newspaper “La Noi”:

“...I chose to respond directly to the newspaper without considering it as a polemic with your young reporter regarding the morality of the years 1924–1926, a time that your reporter so of people, today, in an age that your young reporter did not experience, nor did they know those involved. As evidence, in the article «The Trial that Never Happened», I was portrayed as a fair-haired person, although I have always had brown hair. Building upon this, I wish to emphasize that my letter is not a rebuttal to information gathered by the reporter from various citizens, possibly influenced by ill will but instead aims to present the unadulterated truth of the circumstances in 1924.

...

However, in this letter, I will refrain from delving into the moral or immoral actions of individuals who lived 40–50 years ago. Instead, I will endeavour to demonstrate the clear conscience of these honourable individuals, the Răuceni, who, during their tenure as officials and leaders of Trei Scaune County, conducted themselves with honesty and integrity without accepting illicit funds or bribes. Furthermore, these men, the Răuceanu brothers, not only abstained from receiving such funds but, on the contrary, rejected sums that the law prohibited them from accepting...”

Bibliography:

The Archives of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (ANCSSA), I 0845259 (Vicențiu Rauca-Răuceanu information file), vol. 1 and 2.

- Dan, “Procesul care n-a mai avut loc”, first article of the section: “Memoria arhivei” / “The Memory of the Archive”. Isidor Răuceanu’s response was published in the article: “Pe urmele materialelor publicate : « Procesul care n-a mai avut loc ». See: Cuvântul Nou, Sfântu Gheorghe, V, no. 550, 30 January 1972, p. 2 și no. 580, 5 March 1972, p. 2. https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/CuvantulNou_1972_03.

“Douăzeci și nouă de procese pentru numai o cumnată”, Curentul, I, no. 153, 18 June 1928, p. 4, https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/Curentul_1928_06.

Ioan Lăcătușu, “Isidor Rauca‐Răuceanu, un vrednic primar al orașului Sfântu Gheorghe din perioada interbelică”, https://mesageruldecovasna.ro/isidor-rauca-rauceanu-un-vrednic-primar-al-orasului-sfantu-gheorghe-din-perioada-interbelica/.

Ioan Lăcătușu, “Dr. Vicenţiu Rauca-Răuceanu, prefectul judeţului Trei Scaune (1922–1927), in Cuvântul Nou, new series, Sfântu Gheorghe, IV, no. 976, 29 October 1993, p. 5. https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/CuvantulNou_1993_10.

Petcan, “Scandal politic la Sft. Gheorghe”, in Adevărul, XLI, p. 3, 7 June 1928, no. 13637, https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/Adeverul_1928_06.

Andrei Florin Sora, Servir l’État roumain. Le corps préfectoral, 1866–1940, Bucharest, Bucharest University Press, 2011.

Images:

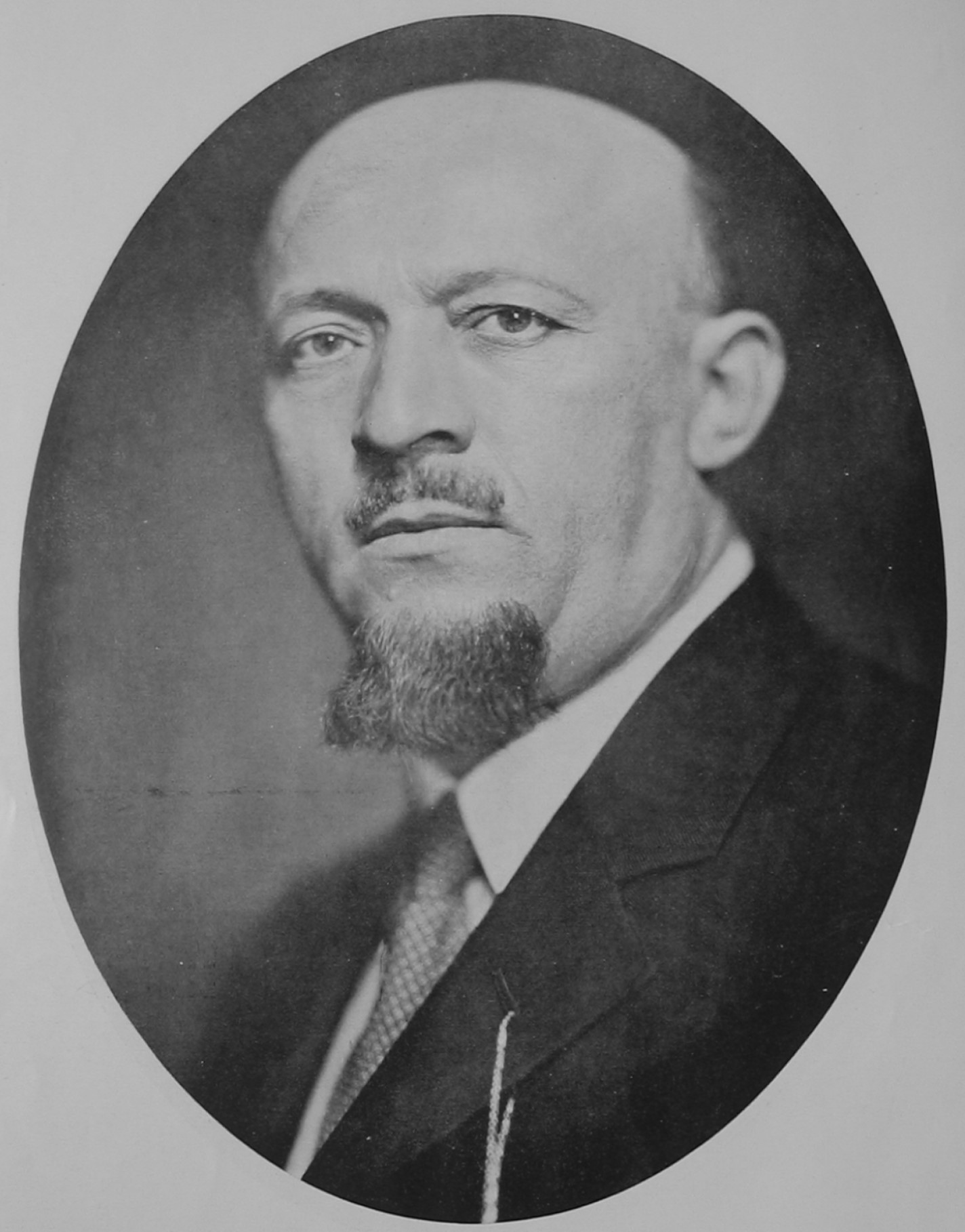

Vicențiu Rauca-Răuceanu, Figuri politice şi administrative din epoca consolidării, Bucharest, 1924, p. 115.

Isidor Rauca-Răuceanu, Figuri politice şi administrative din epoca consolidării, Bucharest, 1924, p. 145.

The Rauca-Răuceanu brothers: a mayor and a prefect in the Trei Scaune County in the 1920s

Isidor Rauca Rauceanu primar - Figuri Politice 1924

The surname Rauca/Róka-Răuceanu was easily recognized during the interwar period among the population of the Trei-Scaune (in Hungarian: Háromszék) County, in the so-called Székely Land, thanks to the brothers Vi(n)cențiu and Isidor (sometimes also spelled Izidor). They were members of the local Romanian-speaking political elite in a county with a majority Hungarian population. Their parents were Elie Răuceanu (?–1924), of Orthodox confession, and Rafira, born Iacob. Besides the two brothers, they had at least one daughter, Ana, who married Cucu.

For an extended period, Elie Răuceanu served as a teacher in Hăghig/Hídvég (Trei Scaune County), a village about approximately equidistant (24 km) from the county seat, Sfântu Gheorghe/Sepsiszentgyörgy, and the major city of Brașov/Kronstadt. In the early 20th century, he held a teaching position at a state school in Tömörkény (Csongrád County) in Hungary. During this tenure, he filed a lawsuit against the Ministry of Education because his name was changed from Răuceanu to Róka (meaning fox in Hungarian) without his consent. This legal action brought him public attention as he went unpaid for several months. Later, his sons Romanianized the Hungarian family name to Rauca, resulting in their surname becoming Rauca-Răuceanu.

Vicențiu was born in December 1889 in Hăghig, while Isidor in May 1891 in Măieruș/Nussbach (Brașov County), a village near Hăghig. Both brothers followed a similar educational trajectory. Vicențiu graduated from the Law Faculty in Budapest (1908–1912) and took his doctorate in January 1914. The younger brother commenced his law studies in Budapest (1911/1912) and continued them in Cluj/Kolozsvár, completing them in 1919. A decade later, Isidor defended his doctorate in Juridical Science at the University of Cluj.

The outbreak of World War I was challenging for the Răuceanu family. While the father was known as a Romanian nationalist, his sons appeared to integrate into Hungarian society. Elie Rauca was considered a Romanian sympathizer in 1916 and interned in a camp. Both brothers were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army. Though the circumstances remain unclear, in a 1972 letter to a local newspaper, Isidor mentioned his status as a war invalid. From this and other sources, it is known that he was appointed as an assessor to the Odorhei/Udvarhely Court of Law in 1915 and briefly served as a County Commissioner (alispán) of Odorhei County in 1916. Vicențiu’s military service details are not fully documented either. He was enlisted in 1914 or 1915, completing his training in Brasov, and was deployed to the front in autumn 1915, attaining the rank of lieutenant by the war’s end.

After the integration of Transylvania into Romania, new opportunities arose for the Răuceanu family. In early 1919, Vicențiu led the Romanian guards in Trei Scaune County. Shortly after that, he was appointed high sheriff (in Hungarian: főszolgabíró; in Romanian: prim-pretor) of the Sfântu Gheorghe District. In 1920, he assumed the role of jurisconsult of Trei Scaune County, only to return to his previous position as high sheriff in the following year (April–July 1921). Isidor also held significant public responsibilities at the local level, serving as a member of various county commissions related to land reform, among other matters. At least during 1919–1920, they aligned themselves with the Romanian National Party and advocated for provincial autonomy. By 1921, however, the brothers shifted their allegiance to the National Liberal Party, originally from the Old Kingdom, and took leadership roles in local party organizations.

Kossuth Lajos Street in Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, postcard

The rise of the Răuceanu family in popularity and local influence coincided with the formation of a Liberal government in January 1922 under the leadership of Ion I.C. Brătianu (1864–1927). Alexandru Iteanu (1869–1928), also from Hăghig, who had pursued studies in Pharmacy in Bucharest and established himself in the Old Kingdom, owning pharmacies and a highly esteemed laboratory named “Flora,” significantly contributed to their growing influence within the National Liberal Party. Despite residing mainly in Bucharest, Iteanu was tasked with establishing a robust liberal organization in Trei Scaune County. For this endeavour, he found reliable allies in the Răuceanu brothers, who possessed deeper connections within local networks. Iteanu assumed the position of prefect of Trei Scaune County in January 1922 but resigned after just two months to become a deputy.

Trei Scaune County Prefecture building (currently Covasna County Library), Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, postcard

Isidor was appointed mayor of Sfântu Gheorghe, the county seat, an office he held from April 1922 to April 1926 and again from June 1927 to June 1928. Two months later, on 22 June 1922, Vicențiu became prefect of Trei Scaune County. Today, local discussions often revolve around the accomplishments of Mayor “Isidor Rauca,” such as the installation of sewerage systems and asphalting of the streets, the modernization of the central park, where he erected a pavilion that stands to this day, and the restoration of several buildings. During his tenure, the prefect Răuceanu boasted various achievements, including constructing 40 schools and renovating dozens of others.

Elisabeth Park (“Central Park”) of Sfântu Gheorghe / Sepsiszentgyörgy, whose development began in 1880, but to which Mayor Isidor Răuceanu also contributed, postcard

The opposition press, in particular, levied numerous accusations of corruption and abuse of power against the two brothers. Vicențiu faced allegations of misappropriating funds from the illegal sale of 150 wagons of corn intended for distribution to the population, abuse of office for personal gain, and intimidation of magistrates. By the end of 1925, he had become the subject of several interpellations in the Romanian Assembly of Deputies, consistently defended by his political patron, Alexandru Iteanu. In April 1926, shortly after the Ion I.C. Brătianu government resigned, Isidor was suspended by a decision of the Sfântu Gheorghe municipal council. He faced accusations of forgery of public documents, embezzlement of public funds, and abuse of office, with this decision being confirmed by the Ministry of the Interior. Isidor Răuceanu received the right to be reinstated in June 1927, only to be suspended again a year later. Meanwhile, Vicențiu stood trial in 1927 for the sale of corn but was acquitted. In 1928, facing the threat of losing his parliamentary immunity, Vicențiu defended himself by accusing the People's Party government (March 1927 – June 1928) of framing him in nearly 20 criminal trials.

The brothers suffered a significant setback when their friendship with Alexandru Iteanu soured. “Curentul,” a Bucharest newspaper, attributed the rift to Mayor Răuceanu's refusal to marry Iteanu’s sister-in-law. In June 1928, despite Vicențiu being an MP, both brothers were expelled from the county organization of the National Liberal Party. Although Alexandru Iteanu passed away in October 1928, the brothers joined a small liberal party ruled by Gheorghe Brătianu (1898–1953), the son of Ion I.C. Brătianu. Since June 1931, with the exception of the 1932 elections, Vicențiu, who also served as the head of the county organization, continuously ran for Parliament on the list of the National Liberal Party – Gheorghe Brătianu, in Trei Scaune County but failed to secure election. On the other hand, Isidor was a parliamentary candidate only in the 1932 elections, representing this party and replacing his brother.

Vicențiu (from 1926) and Isidor (after 1929) pursued careers in law. During the 1920s, Vicențiu was the director of the Sfântu Gheorghe branch of the General Bank of Romania and sat on the member of the Board of Directors of the Credit Bank – Sfântu Gheorghe. Later, from 1936 onward, he assumed the directorship of this institution. He also headed the county's ASTRA branch and was actively involved in the Orthodox Church activities. Both brothers made donations to the church in Hăghig, their hometown. They jointly established the first local political periodical in Trei Scaune County, titled “La Noi,” which was published weekly between 1932 and 1934.

Despite presenting themselves to higher authorities in Bucharest as nationalists, the Răuceanu brothers maintained cordial relations with the Hungarian elites. Furthermore, though it might have been perceived as a flaw for a member of the leadership of a Romanian party, Vicențiu was married to Erzsébet/Elisabeta Sütő, an ethnic Hungarian woman. However, after 1948, despite no evidence to support it, a Securitate (Romanian Secret Police under the communist regime) report labelled Vicențiu, still married to Erzsébet, as a chauvinist. Almost all their real estate was nationalized by the communist regime.

Vicențiu died on 2 April 1954 in Sfântu Gheorghe, and Isidor died in Săcele (Brașov County) on 27 October 1975. Neither of the brothers had children.

At the beginning of 1972, the newspaper “Cuvântul Nou,” published by the county organization of the Romanian Communist Party, featured an article discussing the city of Sfântu Gheorghe in the 1920s, focusing particularly on the alleged wrongdoings of Mayor “Isidor Rauca.” With nothing left to lose and considering the less severe repression against former enemies of the Communist Romania, Isidor Rauca-Rauceanu sent a letter to the newspaper. This text, published in the newspaper, contains subtle irony and a desire to convey to both the public and future generations the administrative achievements of the Răuceanu brothers, along with other benevolent actions such as providing financial support for four pupils (two Romanians and two Hungarians) to pursue high school education, and the establishment of the newspaper “La Noi”:

“...I chose to respond directly to the newspaper without considering it as a polemic with your young reporter regarding the morality of the years 1924–1926, a time that your reporter so of people, today, in an age that your young reporter did not experience, nor did they know those involved. As evidence, in the article «The Trial that Never Happened», I was portrayed as a fair-haired person, although I have always had brown hair. Building upon this, I wish to emphasize that my letter is not a rebuttal to information gathered by the reporter from various citizens, possibly influenced by ill will but instead aims to present the unadulterated truth of the circumstances in 1924.

...

However, in this letter, I will refrain from delving into the moral or immoral actions of individuals who lived 40–50 years ago. Instead, I will endeavour to demonstrate the clear conscience of these honourable individuals, the Răuceni, who, during their tenure as officials and leaders of Trei Scaune County, conducted themselves with honesty and integrity without accepting illicit funds or bribes. Furthermore, these men, the Răuceanu brothers, not only abstained from receiving such funds but, on the contrary, rejected sums that the law prohibited them from accepting...”

Bibliography:

The Archives of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (ANCSSA), I 0845259 (Vicențiu Rauca-Răuceanu information file), vol. 1 and 2.

- Dan, “Procesul care n-a mai avut loc”, first article of the section: “Memoria arhivei” / “The Memory of the Archive”. Isidor Răuceanu’s response was published in the article: “Pe urmele materialelor publicate : « Procesul care n-a mai avut loc ». See: Cuvântul Nou, Sfântu Gheorghe, V, no. 550, 30 January 1972, p. 2 și no. 580, 5 March 1972, p. 2. https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/CuvantulNou_1972_03.

“Douăzeci și nouă de procese pentru numai o cumnată”, Curentul, I, no. 153, 18 June 1928, p. 4, https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/Curentul_1928_06.

Ioan Lăcătușu, “Isidor Rauca‐Răuceanu, un vrednic primar al orașului Sfântu Gheorghe din perioada interbelică”, https://mesageruldecovasna.ro/isidor-rauca-rauceanu-un-vrednic-primar-al-orasului-sfantu-gheorghe-din-perioada-interbelica/.

Ioan Lăcătușu, “Dr. Vicenţiu Rauca-Răuceanu, prefectul judeţului Trei Scaune (1922–1927), in Cuvântul Nou, new series, Sfântu Gheorghe, IV, no. 976, 29 October 1993, p. 5. https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/CuvantulNou_1993_10.

Petcan, “Scandal politic la Sft. Gheorghe”, in Adevărul, XLI, p. 3, 7 June 1928, no. 13637, https://adt.arcanum.com/ro/view/Adeverul_1928_06.

Andrei Florin Sora, Servir l’État roumain. Le corps préfectoral, 1866–1940, Bucharest, Bucharest University Press, 2011.

Images:

Vicențiu Rauca-Răuceanu, Figuri politice şi administrative din epoca consolidării, Bucharest, 1924, p. 115.

Isidor Rauca-Răuceanu, Figuri politice şi administrative din epoca consolidării, Bucharest, 1924, p. 145.

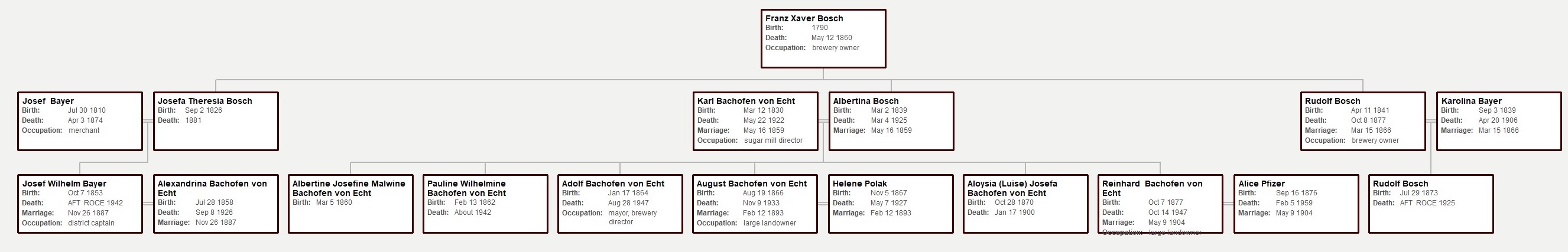

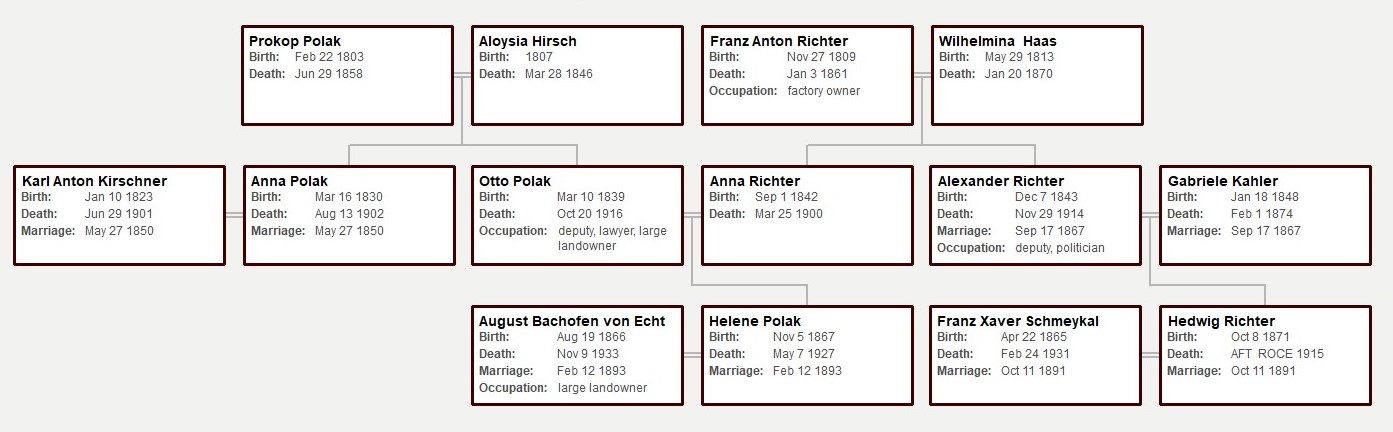

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

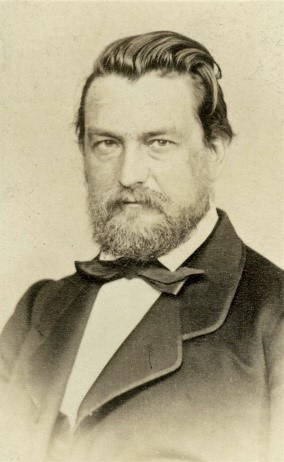

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

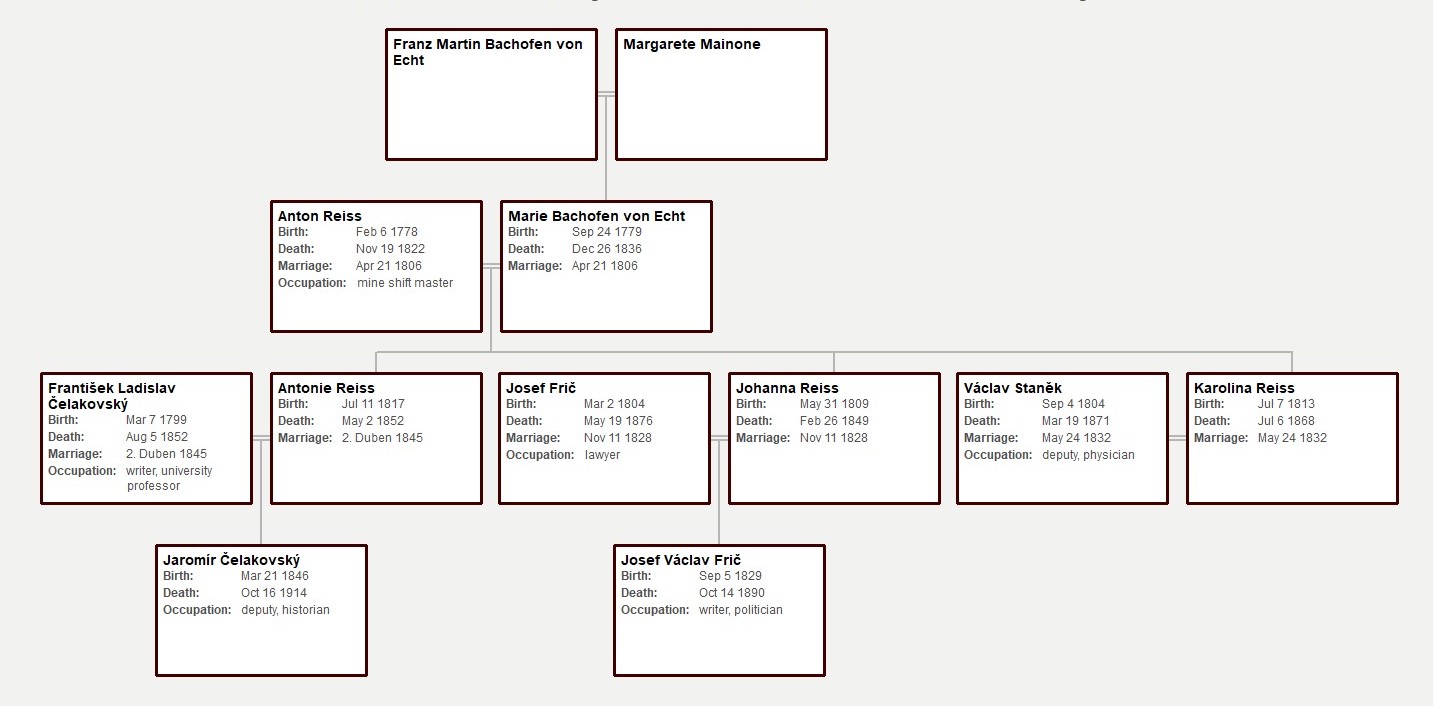

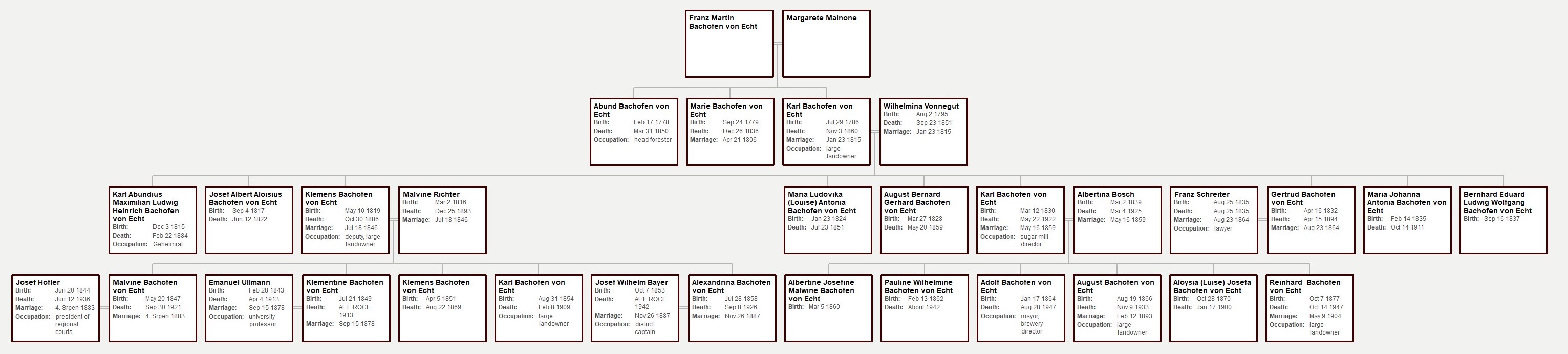

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

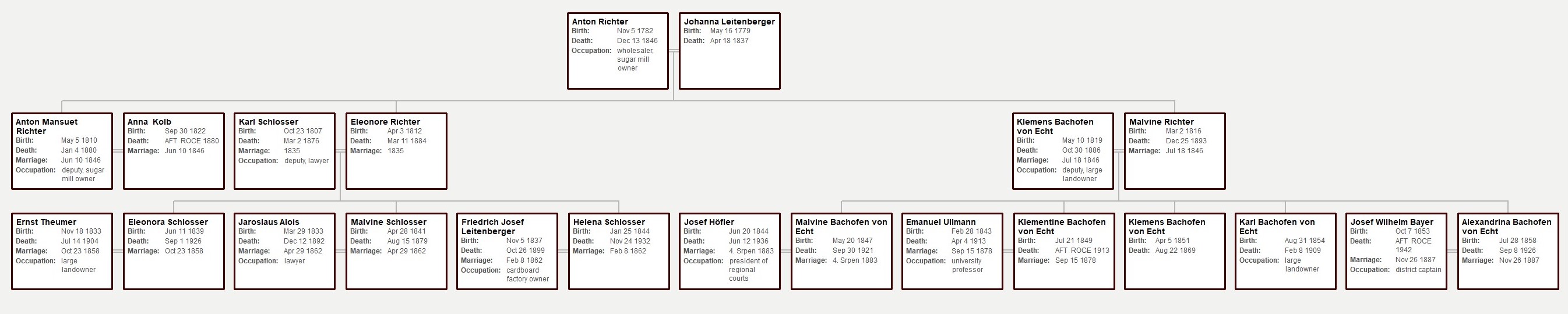

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

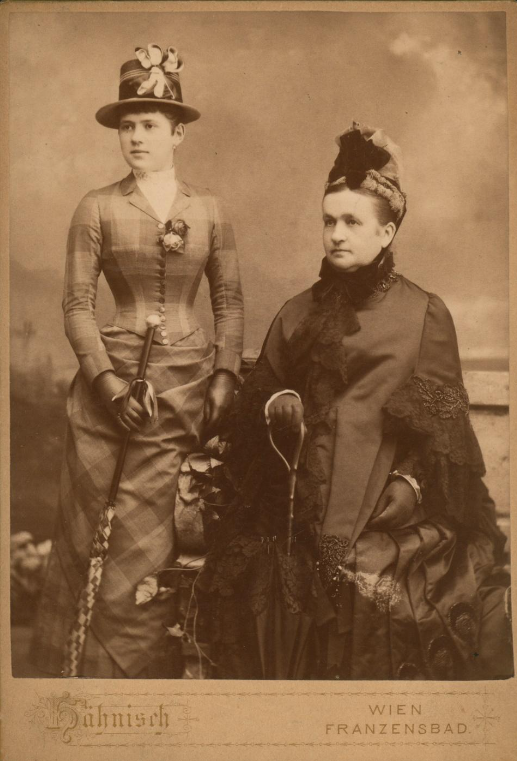

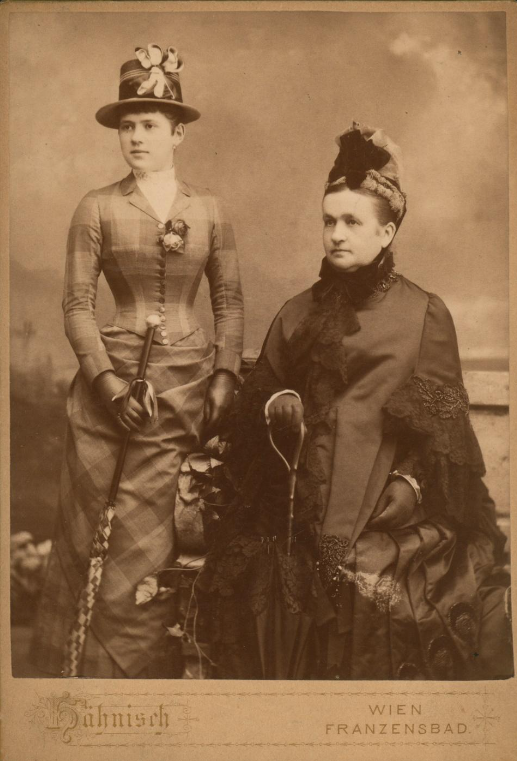

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

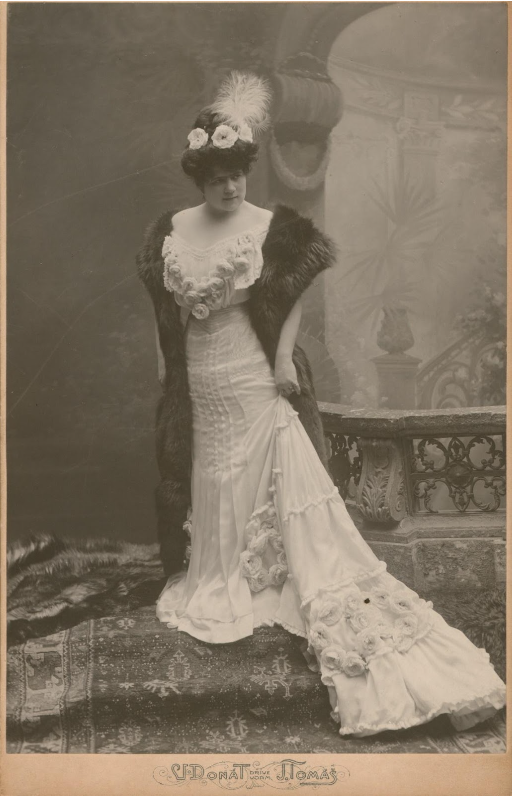

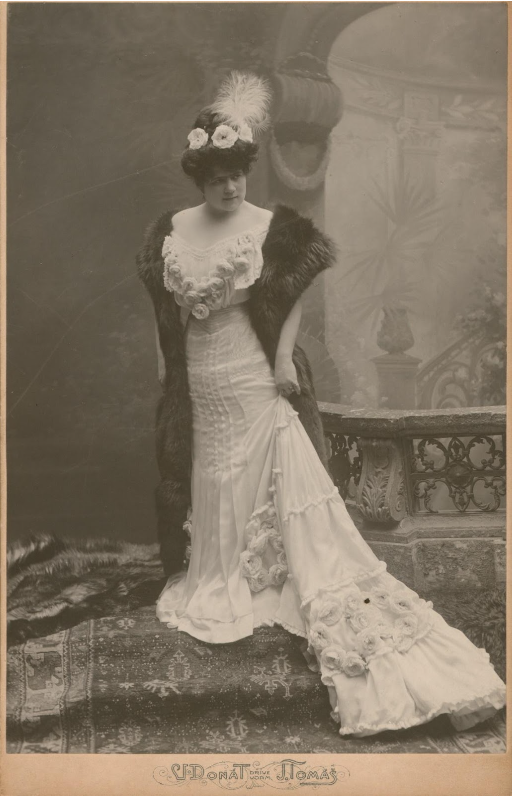

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.