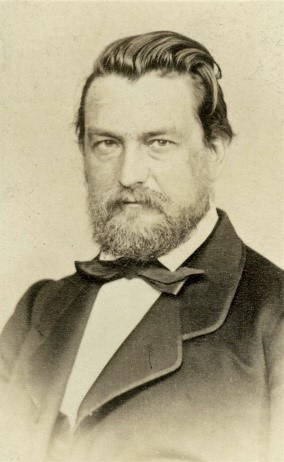

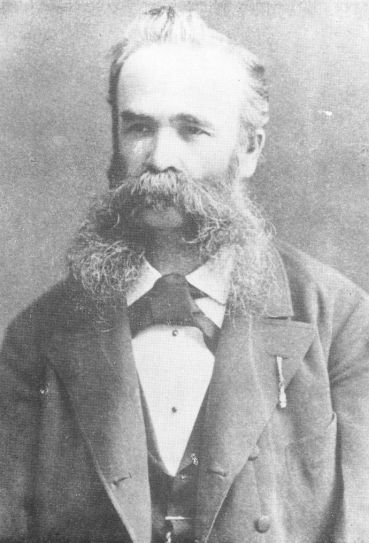

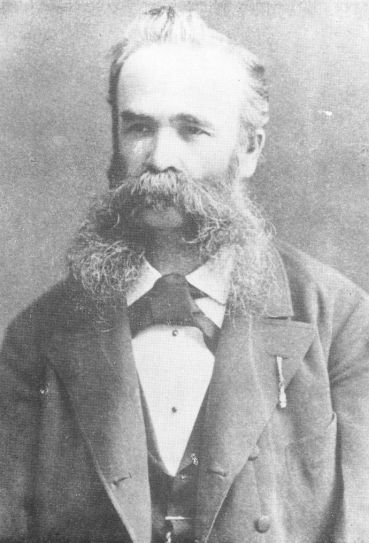

Count Manó (Emánuel) Péchy (1813–1889)

The Péchy family received the noble charter from Ferdinand I. at the beginning of the 16th century. The extended family held important positions in Sáros county, several of them were county commissioners (alispán), but later they also spread to other counties. The MP’s father József Péchy was a landowner in Abaúj-Torna county, and for his financial help in the Napoleonic Wars he was awarded the title of count in the early 19th century (1810). So when Emánuel / Manó Péchy was born in 1813 in the family castle in Boldogkőváralja, Abaúj county, the ink was barely dry on his father’s aristocratic rank.

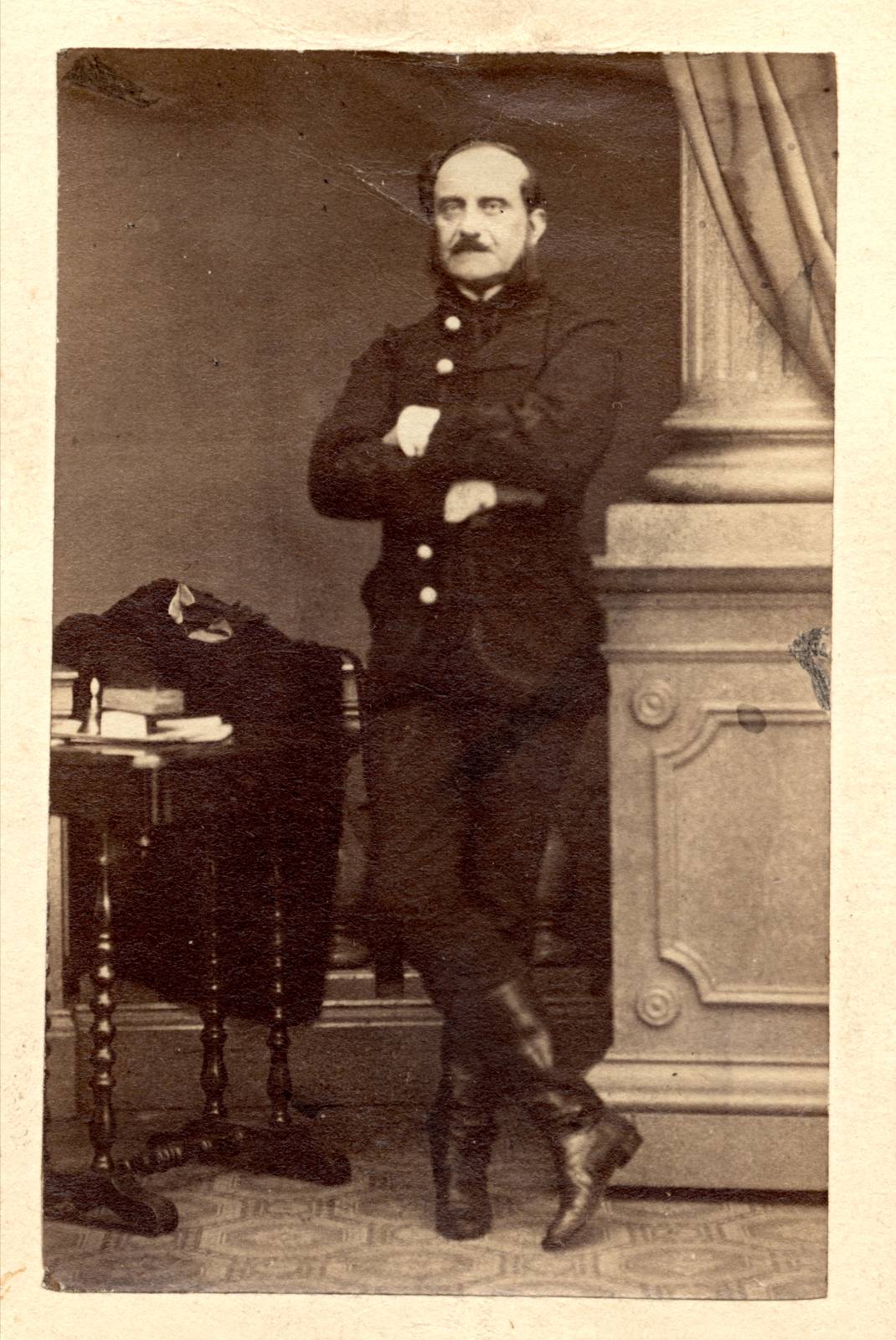

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Péchy passed the bar exam in 1834, after studying law at the Academy of Law in Košice (Kassa). In the 1839–40 Diet he became a representative of Abaúj county, after having been vice- and then chief county notary for a short time. His loyal attitude in the Diet probably contributed to the fact that at the end of 1841 Archduke Joseph (1776–1847), the Palatine of Hungary, appointed him as the administrator of the Zemplén county, which was adjacent to Abaúj. However, Péchy’s early career was interrupted by the revolution of 1848.

In 1844 he married Baroness Zenaida Meskó (1828–1861), the younger daughter of Baron Jakab Meskó and Count Anna Fáy. The Meskó sisters were considered a very good party, because in the absence of a male heir, they inherited the entire family fortune. It seems that the older sister, Irén, was intended for Péchy first. We do not know the reason why this marriage failed, but the fact is that in 1843 Irén married count Henrik Zichy (1812–1892), while Péchy married the younger sister Zenaida a year later. His only brother Konstantin (1821–1866), who was an officer in the army, was married to Count Irma Forgách (1822–1872), also from an aristocratic family in the area.

Although conservative, Péchy did not take office during the years of neo-absolutism; he retired to his estate to wait for better times. Following the October Diploma (1860), the Hungarian counties were restored. Péchy was appointed as the Lord-Lieutenant of Abaúj county and the city of Košice (Kassa). The following year, however, he resigned, as did most of the Lord-Lieutenants. The new Chancellor count Herman Zichy (1814–1892) was the brother of Péchy’s brother-in-law Henrik Zichy.

In 1865, as a prelude to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, new Lord-Lieutenants were partly appointed and parlty reinstated, including Péchy, as the head of Abaúj county and Košice. However, his career took a new direction after the Compromise. At that time, he was appointed Royal Commissioner for Transylvania, with the task of overseeing the integration of Transylvania, advising the Hungarian government and reducing ethnic tensions. His appointment was initiated by the Prime Minister, Gyula Andrássy (1823–1890), with whom they had known each other since Péchy was the county administrator of Zemplén County.

After the abolition of the royal commissioner’s office (1872), Péchy’s ties with Transylvania loosened, if not completely disappeared. From 1872 he was a member of the Parliament of Cluj (Kolozsvár) for three terms. Subsequently, in 1881, he was elected in Košice, where he began his political career. His name came up a few times in political combinations: as Minister of the Interior and, in 1879, as Minister of Finance. But no further political role awaited him. The elderly Péchy was a member of the upper house of parliament.

In his private life he suffered many adversities. Several of his children died in infancy and his only son was killed in an accident when he was ten. His wife never recovered from this loss, and died in 1861 after a long illness. He did not remarry after his wife’s death, although there are several hints of his gallant adventures. Perhaps the most controversial was his affair with a young actress in Košice, Lujza Nagy (1843–1911). His only daughter Jaqueline Péchy (1846–1915) was brought up by his brother-in-law Henrik Zichy in Moson County until she married Henrik’s younger brother Rudolf (1833–1893) – stepson of the famous Hungarian politician István Széchenyi (1791–1860) – in 1864. Jaqueline had seven children, but she was unable to see her younger children because she became blind at a young age.

Manó Péchy even lived to see one of his grandchildren, Eleonóra Zichy (1867–1945), marry the son of the former Prime Minister and later Foreign Minister of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Gyula Andrássy, Tivadar (1857–1905) (and after his death to his other son Gyula Andrássy Jr., 1860–1929). Katinka Andrássy (1892–1985), the great-granddaughter of Manó Péchy, one of the couple’s daughters, became famous as the “Red Countess”. She was the wife of Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955), the Prime Minister and later President of the Republic who came to power in 1918 after the so-called Aster Revolution.

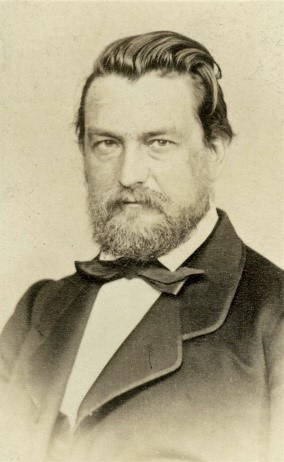

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Manó Péchy died in the summer of 1889 in Boldogkőváralján, in his family castle.

Boldogkőváralján residence Boldogkőváralján castle

Bibliography

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Aristokrat v službách štátu. Gróf Emanuel Péchy, Bratislava, Kalligram, 2006.

Judit Pál, Unió vagy „unificáltatás”? Erdély uniója és a királyi biztos működése (1867–1872) (Union or "unification"? The Union of Transylvania and the functioning of the Royal Commissioner). Kolozsvár, Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2010.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Emanuel Péchy ako župan Abova a Košíc. In: Historica Carpatica. Zborník Východoslovenského Múzea v Košíciach 35 (2004). Vydalo Východoslovenské múzeum v Košiciach, 2004, pp. 55–72.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Štyri stretnutia a dve kariéry (gróf Gyula Andrássy a gróf Emanuel Péchy). In: Acta Historica Historica Neosolensia, tomus 9, Banská Bystrica, Katedra histórie FHV Univerzity Mateja Bela, 2006, pp. 65–80.

Judit Pál, Péchy Manó – a „mintahivatalnok” (Manó Péchy the „model official”). Erdélyi Múzeum. LXIX. (2007) no. 1–2, pp. 33–61.

Judit Pál – Roman Holec, Gróf Emanuel Péchy ako kráľovský komisár Sedmohradska (1867–1872). In: Historické štúdie. roč. 45 (Bratislava, 2007), pp. 169–203.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Dvaja vysokí štátni úradníci – dva integračné pokusy – dve „imperiálne kariéry“? (knieža Karl Schwarzenberg a gróf Emanuel Péchy v Sedmohradsku). Historický časopis, vol. 62 (2014) nr. 3. pp. 447−470.

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

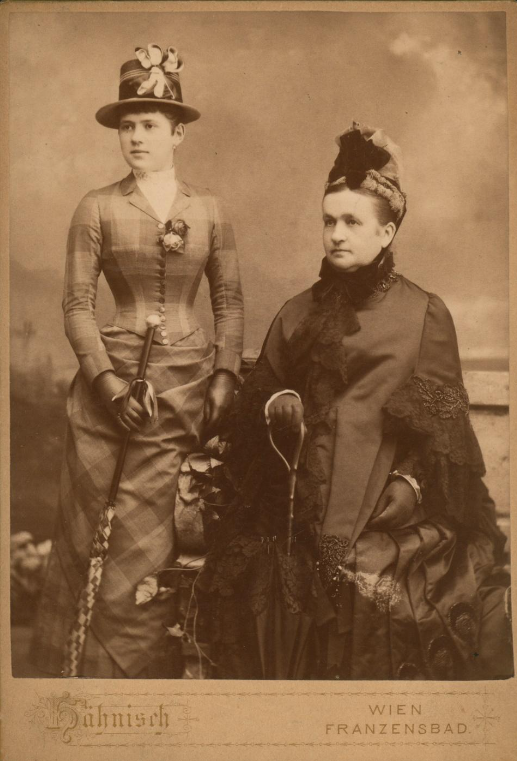

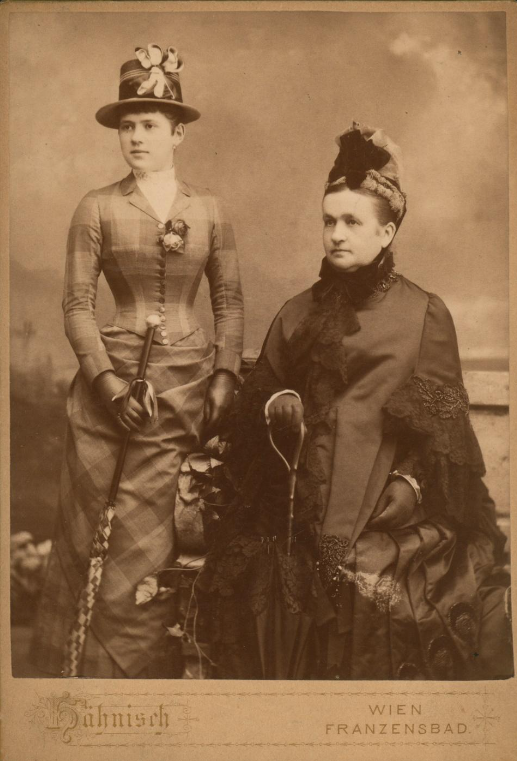

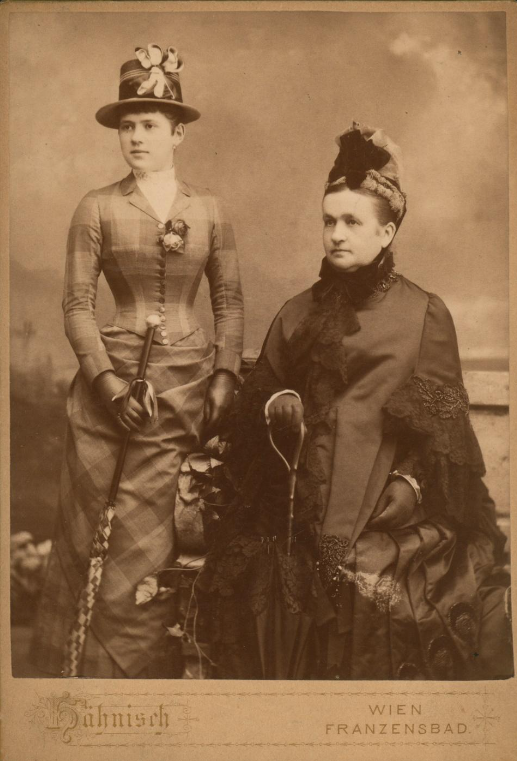

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

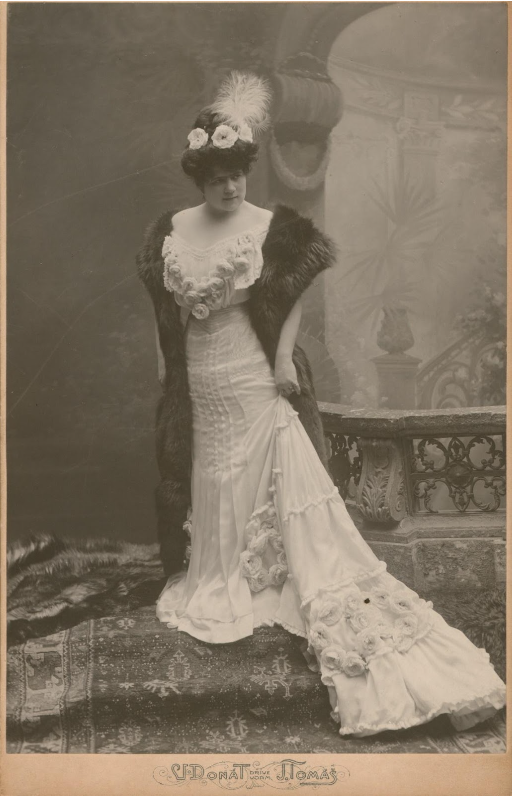

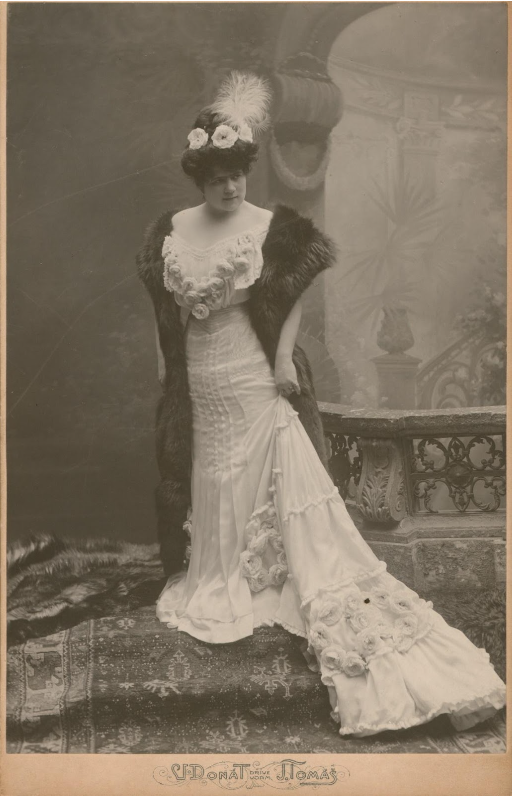

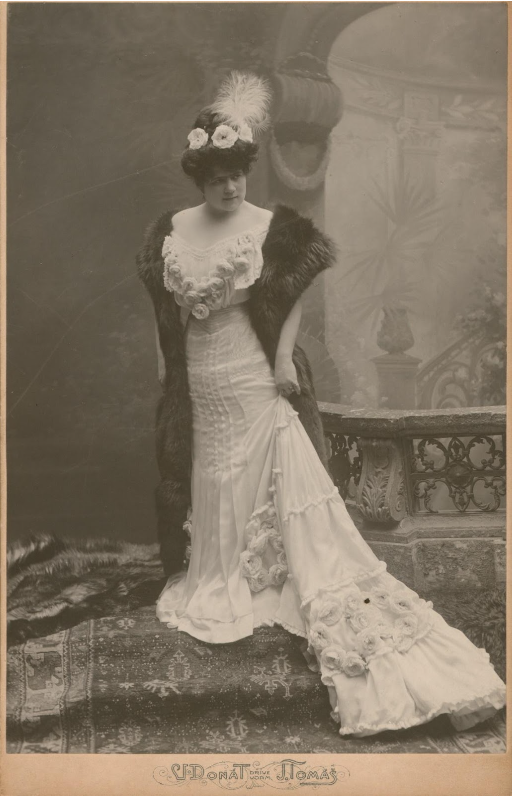

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

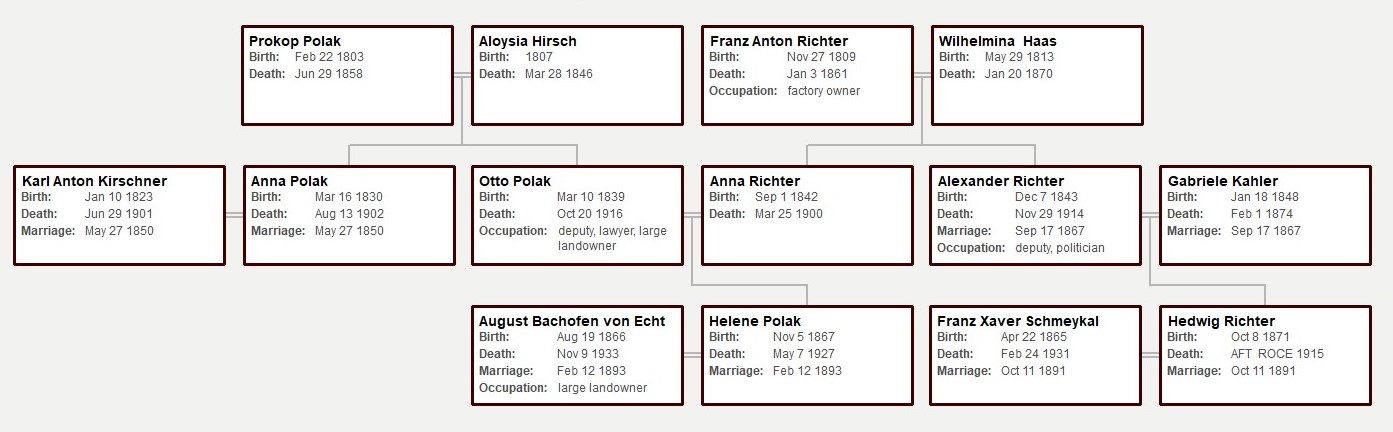

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

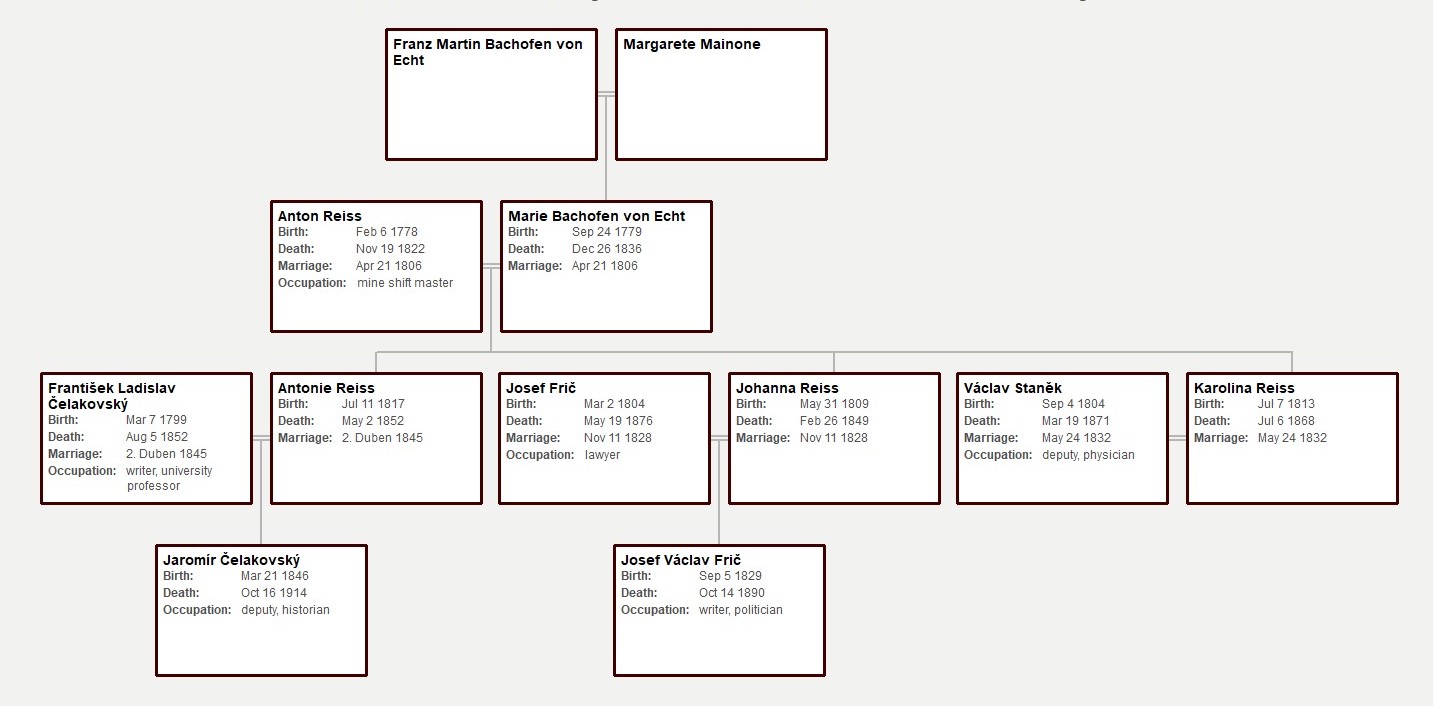

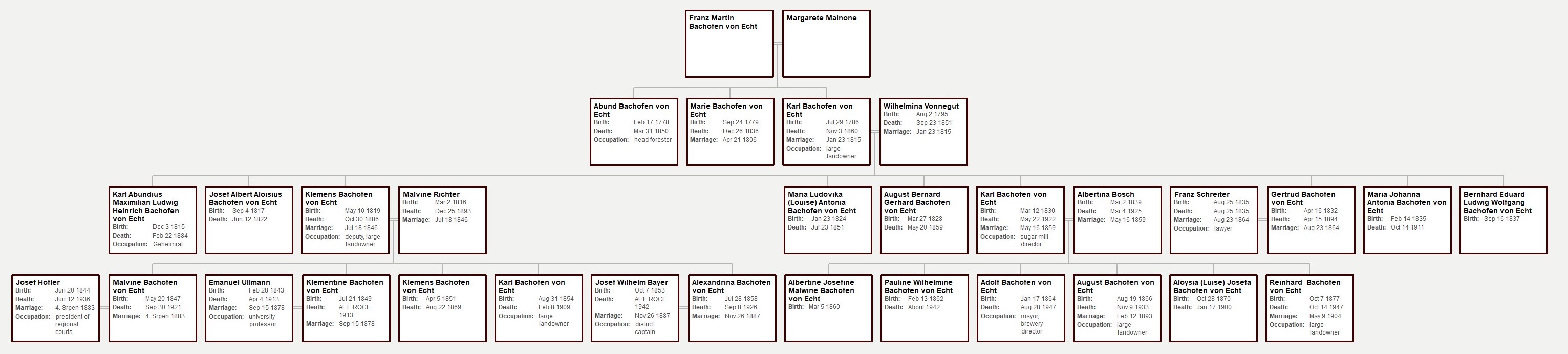

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

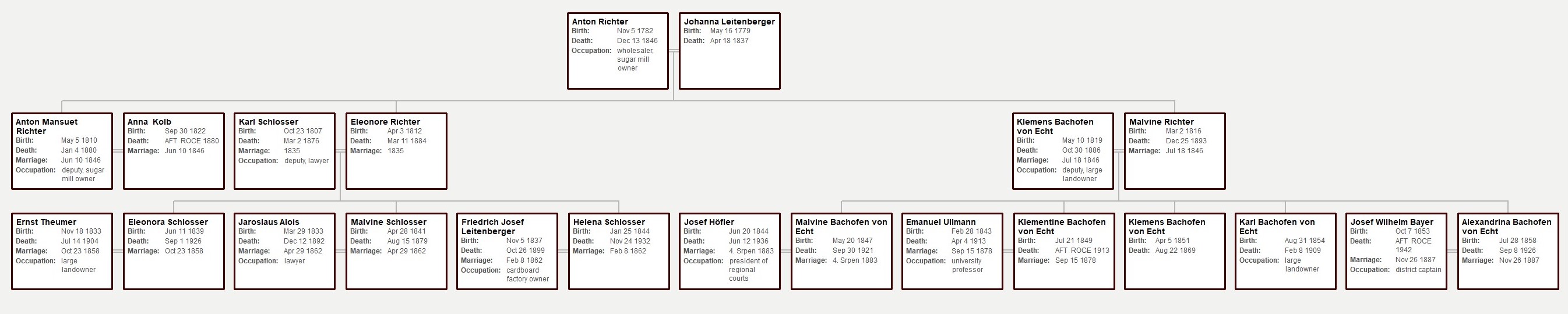

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

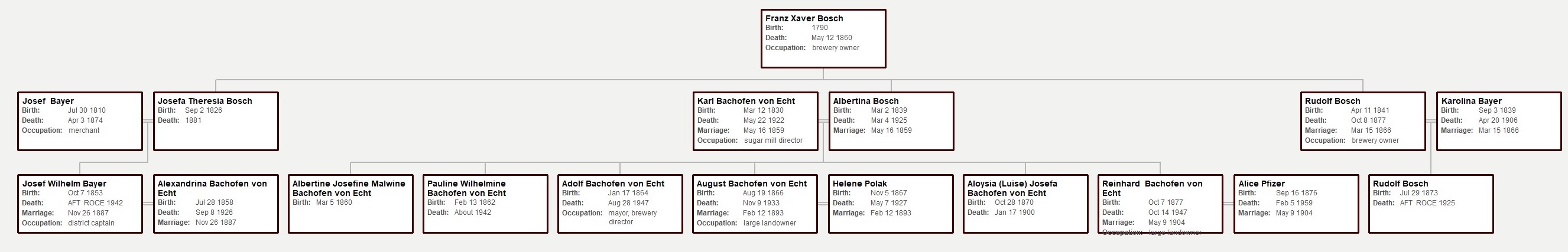

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

Vasile Ladislau Pop (1819–1875) came from a priestly family of noble origin, living in Berind (Berend, Kolozs County). He was the second of the ten children of priest Ananie Pop and his wife, Anastasia. He attended elementary, secondary, and high school classes at the Roman Catholic (Piarist) High School in Cluj, where he was among the most diligent pupils of his generation. During this formative period he received a middle name that is the translation from Romanian into Hungarian of his first name (Vasile, which became Ladislau), thus resulting in his full name Vasile Ladislau Pop. After graduating from high school in 1835, he enrolled at the Faculty of Law in Cluj, which he graduated three years later. In 1838, thanks to his father’s intervention with Ioan Lemeni (1780–1861), the Greek Catholic Bishop of Blaj, he obtained a scholarship to study at the Theological Faculty of the University of Vienna, as a student of the Saint Barbara Seminary. Four years of theological studies followed in the capital of the Austrian Empire, where young Vasile Ladislau Pop completed his formative profile with theoretical notions and the German language, which were to be particularly useful in his later career. The Viennese studies facilitated his insertion into an extremely complex formative environment, which allowed access to readings and ideological trends that proved to be particularly stimulating for his political and cultural horizon. It was during this period that Vasile Ladislau Pop came to study the works of Transylvanian Romanian illuminists, such as Petru Maior (1756–1821), Gheorghe Șincai (1754–1816), and Samuil Micu (1745–1806), who historically and linguistically affirmed and legitimized the Roman origin of the Romanians as an indisputable argument for recognizing the Romanians as a political nation with equal rights alongside the other political nations in Transylvania.

Image source: “Oameni de știință și cultură din Reghin și împrejurimi”, Album, 11, Petru Maior Municipal Library (Biblioteca Municipală Petru Maior), Reghin, http://www.bibliotecareghin.ro/index.php?Book=43.

After completing his studies in Vienna, Vasile Ladislau Pop returned to Transylvania, where he was appointed teacher of mathematics at the Theological Seminary in Blaj. Although he taught there for only three years, until 1845, his pupils and posterity remember him as the first teacher who taught mathematics in Romanian at the Seminary in Blaj. During the time he spent in Blaj, he also met a new generation of teachers, such as Ioan Rusu (1811–1843), Ioan Cristoceanu (1810–1844), and Demetriu Boieriu (1812–1871), with whom he became close. With some of them, he established a long-lasting friendships. We particularly refer to the teacher, historian, philosopher, and politician Simion Bărnuțiu (1808–1864), with whom he shared the same ideals and political-cultural projects aimed at the recognition of political rights for the Romanians in Transylvania.

His friendship with Bărnuțiu drew him into the Lemeni conflict in Blaj, during the period 1843–1846, between the new generation of teachers and the older one grouped around Bishop Ioan Lemeni, which led to his expulsion from Blaj.

The road to “Vienna, to the Emperor’s right hand”

For Vasile Ladislau Pop, the expulsion from Blaj (1845) was a major turning point in his professional career. Sent by his father to study theology to become a priest, but expelled by his bishop because of divergent opinions, Vasile L. Pop decided to abandon his clerical career for good to pursue a legal career. That was the moment in which he promised his father that he would only return home when he “arrived at the right hand of the Emperor”. Consequently, in the same year 1845, he enrolled in law studies at the Royal Board (Court of Appeal) in Târgu Mureș, which he graduated in 1848, obtaining a lawyer’s diploma. He began his career in Reghin, where he had met the young Elena Olteanu in 1846, and married her in the autumn of 1848. From the very beginning of his legal career, he benefited from the support of the Olteanu family and their relatives, which made it easier for young Vasile L. Pop to enter the intellectual circles of Transylvania. Vasile L. Pop’s in-laws, a family of merchants, enjoyed a good reputation in the area, and Elena’s maternal uncle, also a merchant, openly assumed his support for the two.

In 1849, Vasile L. Pop was appointed district commissioner in Reteag (Bistrița County), and shortly afterward, legal advisor at Bistrița Justice Court. It was the beginning of an ascending administrative-political career, which took him, in the next two decades, to the highest positions and dignities held by a Transylvanian Romanian until then. After working as a legal advisor in Bistrița (1852) and as a legal advisor at the Supreme Court in Sibiu (1854), he was promoted to a legal advisor at the Ministry of Justice in Vienna (1859). The peak of his career came in the years of the “liberal thaw” at the beginning of the seventh decade of the nineteenth century, when he was named vice-president of the Transylvanian Government and president of the Transylvanian Supreme Court. In 1863, he was appointed private councilor of the Emperor. He was only 45 years old at the time and had managed, thanks to the superior education he had benefited from and to the support of his parents-in-law’s family, to take up some of the highest state positions held by a Romanian up to that point. He also participated as a deputy in the proceedings of the Transylvanian Diet in Sibiu, in 1863 and 1864. In that capacity, he helped to draft laws meant to establish rights for the Romanians, which were going to be equal with those of the other nations inhabiting Transylvania.

With the signing of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Vasile L. Pop was designated vice-president of the Court of Cassation in Budapest, a position he held until the end of his life. Moreover, in recognition of his merits in the service of the Romanians of Transylvania, in 1868, he was elected chairman of the Astra Association (Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People). He died on February 17, 1875, in Budapest, and was buried in Reghin, in the Olteanu family crypt.

The case of Vasile L. Pop is a good example of the social mobility of an individual who, coming from a priestly family, left this socio-professional category and pursued a legal career, which propelled him to the top of the political pyramid of Transylvania in the years of Austrian neoliberalism. Pop’s marriage to Elena Olteanu, her family’s support, and the kinship networks created around this family contributed to his social ascent.

Bibliography:

Federațiunea, 11–12, MDCCCLXXV, 9/21 February 1875, 33.

Transilvania. Foia Asociațiunii transilvane pentru literatura și cultura poporului român, 5, VIII, 1 March 1875, 49–51.

Nicolae Comșa, Dascălii Blajului. Seria lor cronologică cu date bio-bibliografice (Blaj: Tipografia Seminarului, 1940).

Elie Dăian, Al doilea președinte al Asociațiunii: Vasile L. bar. Pop 1819–1875 (Sibiu: Editura “Asociațiunii”, 1925).

Solomon Haliță (1859–1926)

Image source: here.

Maxim Haliță (1826–1893) came from a border guards family in Sângeorz Băi (Sângeorzul Român, Oláhszentgyörgy). He started as a village teacher during the 1840s, then served in the 17th (2nd Romanian) Border Guards Regiment during the Revolution of 1848–1849. After the military border system in the area was decommissioned he started a career in local administration: village notary (1851–1872), clerk to the district sheriff’s office (1873–1873), district sheriff (1873–1875), royal head-postman (1875–1889). In 1852 he married Ileana Ciocan (adopted by the family Isipoaie), and fathered four children: Elisabeta (1853–1915), Axente (1856–1865), Solomon (1859–1926) and Alexandru (1862–1933). (more, here)

His children were part of the first generation of young people who benefited from financial support for their studies, provided by the Border Guards’ Funds, an institution created following the decommission of the military border.

Elisabeta studied at the girls’ school in Năsăud (Naszód), then in Bistrița (Bistritz, Beszterce) and married Grigore Marica, a priest from Coșna – a nearby village. In 1879, her husband died after being accidentally wounded by her brother, Solomon Haliță (20 years old at the time), while returning from a hunting trip. As a consequence, Solomon vowed not to marry and have children, but to raise his three orphaned nephews, which he did, supporting them throughout their life. (more, here)

The youngest son, Alexander, studied Greek-Catholic Theology at Gherla (Szamosújvár) (1884–1888) and Letters at the Francis Joseph University in Cluj (Kolozsvár) (1888–1893). He was a teacher at the Highschool in Năsăud (1891–1911, 1920–1928), as well as parish priest of Năsăud and curate of Rodna (1911–1920). (more, here)

The best-known member of the family, however, was to become Solomon Haliță. He studied at the Highschool in Năsăud, where he distinguished himself and was also actively involved in the school’s literary societies (both the authorized and the secret ones). These societies were at the time a hotbed of Romanian nationalism and some of Haliță’s colleagues (Ioan Macavei (1859–1894), Corneliu Pop Păcurariu (1858–1904)) would later become journalists of the radical nationalist political newspaper “Tribuna”, and would spend time in prison for their articles. Haliță went on to study History and Philosophy, and Pedagogy at the University in Vienna, where he joined the Romanian Students’ Society “România Jună”, but also a smaller literary club called “Arborele” (The Tree), of only 17 members. The main objective of this club was to spread the cultural ideas from the Old Kingdom of Romania (in particular those of the “Junimea” Society) among the Romanians in Transylvania. (more, here) It is worth noting that more than half of its members later became public figures in the Romanian cultural and political milieu, and at least one of them (Septimiu Albini) linked up with Haliță’s former high school mates in the editorial office of “Tribuna”, and later also served time for press offences. (more, here)

After completing his studies in 1883, Haliță had difficulties finding a tenured teaching position back home, although, truth be told, he did not seem to have the patience to wait for an opening, as he emigrated very soon to Romania. In 1890 he renounced his Hungarian citizenship and became a citizen of the Kingdom of Romania. Between 1883 and 1919 he worked as a secondary school teacher in various towns, while at the same time building a bureaucratic career in the field of Public Education: 1889–1891, member of the General [i.e., National] Council of Instruction; 1896–1899, 1901–1904, 1907–1911, and 1914–1919 General Inspector of Schools. Much of his success was owed to the good relationship he developed with Spiru Haret, an important liberal reformer of education in early 20th century Romania. (more, here)

During the First World War, and especially during the retreat of the Romanian political authorities to Iași (1916–1918) Haliță developed even closer ties with representatives of the National Liberal Party, and in particular with Prime Minister, Ion I.C. Brătianu. Thus, he slowly shifted from being just an efficient and well-regarded bureaucrat in the field of Education to handling more sensitive political issues. In October 1918, he played the role of intercessor between the Romanian delegates from Transylvania and the Romanian government. He was then sent back to Transylvania to accompany Brătianu’s messages of political and military support and took part, in this capacity, at the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918. (more, here) This privileged position explains his temporary appointment as prefect of Iași in 1919. (more, here)

Between 1920 and 1922 Haliță returned to Transylvania as General (i.e., Regional) Inspector of Schools. In 1922 he was appointed prefect of his home county, Năsăud (Bistrița-Năsăud after 1925), an office he held until the fall of the Liberal government in April 1926. It was the peak of his career, something nobody would have envisioned forty years earlier, when he had left the same county as an émigré due to not finding a tenured teaching position. He died a few months later, on 1 December 1926.

Solomon Haliță’s career highlights the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the financial support for education in the former Austrian military border area, due to the transformation of regimental funds into educational and scholarship funds. It also illustrates the constant migration of Romanian university graduates from Austria-Hungary to Romania, which populated the civil service of the latter with highly qualified personnel, at all levels and in all branches of activity. Last but not least, it shows how the combination between professionalism and personal relationships (also built along professional lines), helped maintain a high bureaucratic position despite the changes in government, and how political support helped the leap from the ministerial bureaucracy to the administrative and political elite.

Literature

Septimiu Albini, Direcția nouă în Ardeal. Constatări și amintiri, in vol. Lui Ion Bianu amintire. Din partea foștilor și actualilor funcționari ai Academiei Române la împlinirea a șasezeci de ani, București, 1916. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban, Maxim Haliță – locuitor de frunte din Sângeorgiul Român, în „Arhiva Someșană”, XV, 2017. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban (ed.), Solomon Haliță, om al epocii sale, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2015. (here)

Ironim Marţian, Figuri de dascăli năsăudeni şi bistriţeni, Editura Napoca Star, Cluj–Napoca, 2002.

Adrian Onofreiu, Ana Maria Băndean, Prefecții județului Bistrița–Năsăud (1919–1950; 1990–2014). Ipostaze, imagini, mărturii, Bistrița, Charmides, 2014.

Grigore Pletosu, Moarte prin puşcă, în „Telegraful Român”, XXVII, 1879, nr. 91, 7 august, p. 359. (here)

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

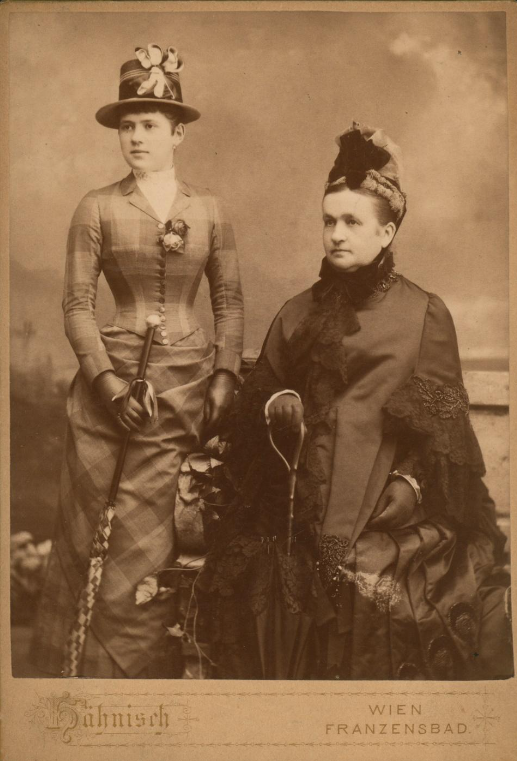

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

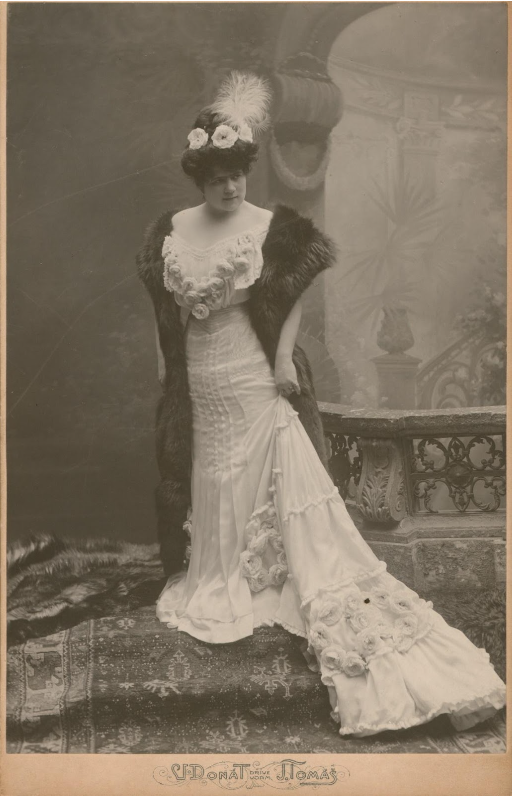

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14