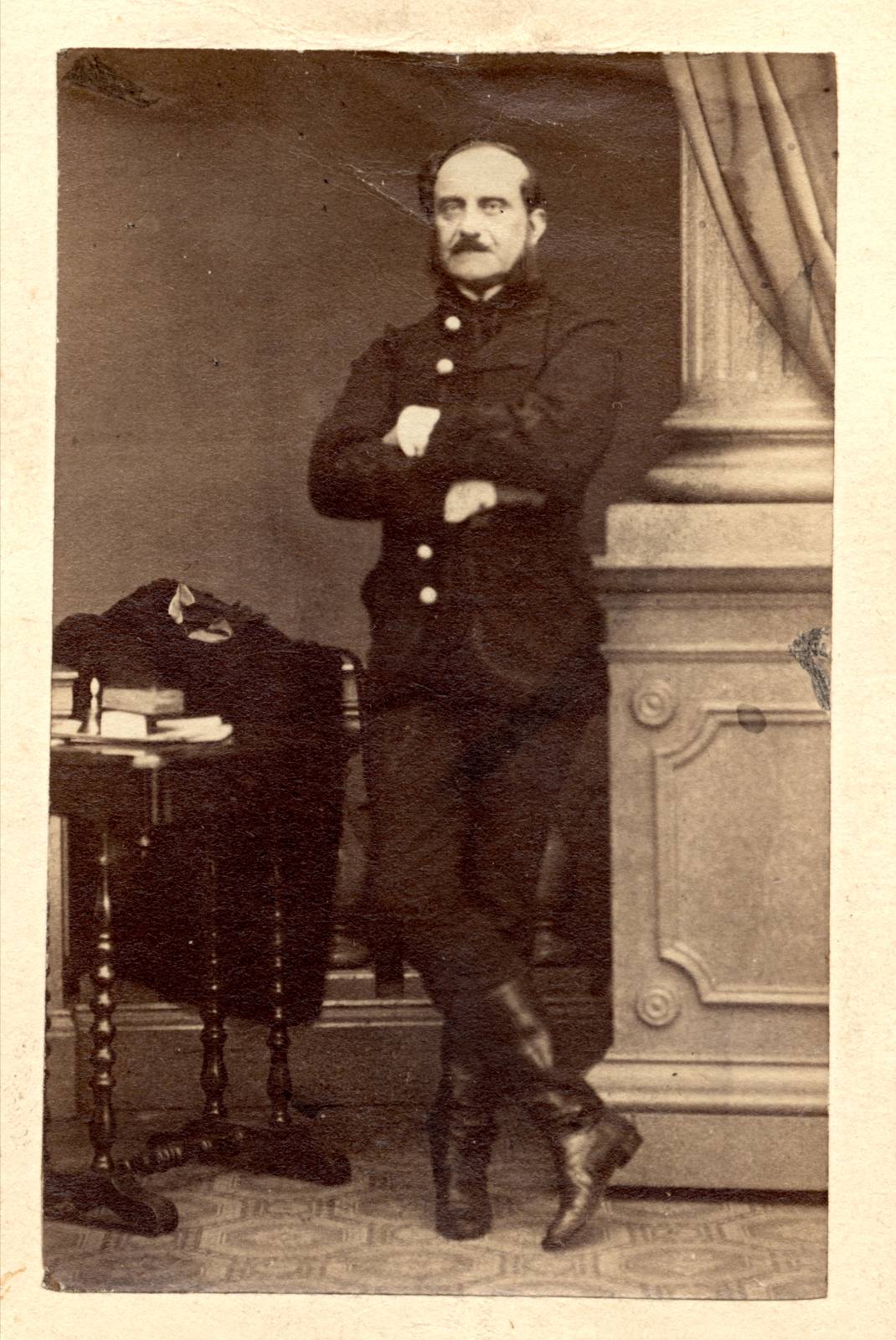

Mara Lőrinc of Felsőszálláspatak/Sălașu de Sus was born in 1823 in Székelyföldvár/ Războieni-Cetate (by then in the Székely seat of Aranyos/Arieș, Transylvania).

His grandfather, bearing the same name, was assessor at the Royal Judicial Court of Transylvania. An uncle bearing the same name was officer during the Napoleonic Wars. His father, József, was provincial commissioner and later on royal judge of the respective seat, but the family also held land properties in Hunyad/Hunedoara county. He had seven children: six boys (Miklós, Lőrinc, Károly, Gábor, Sándor and György) and one girl (Ágnes, married to baron Kemény István).

Mara Lőrinc followed a military career, he graduated from the Imperial and Royal Technical Military Academy (k.u.k. Technische Militärakademie, further reading here) and served as Junior Lieutenant in the Székely Border Guards Regiment from Csíkszereda/Miercurea Ciuc. During the 1848–1849 Revolution he served as captain in the Hungarian Honvéd Army, together with other members of the extended family (e.g., here), for which he was initially sentenced to death, but later pardoned after four years of imprisonment at Olomouc/Olmütz. In the 1860s he entered political life, as district sheriff (szolgabíró) and county commissioner (alispán). As a follower of Tisza Kálmán’s (1830–1902) party, and after two unsuccessful candidacies he finally managed to obtain a parliamentary seat in 1875, in the constituency of Hátszeg/Hațeg (in which the family estates were situated), after his party’s coming to power. He represented the constituency between 1875 and 1886 (see here), and died in 1893.

Mara Lőrinc was an epitome of Tisza Kálmán’s “mamelukes” – as the supporters of the Hungarian Liberal Party were called at the time – and the literary works of Mikszáth Kálmán (1847–1910) shed some light on the intricacies of his relationship with the voters, most of them Romanian villagers. Mikszáth recounts that, when one of the opposition’s candidates Kaas Ivor (1842–1910) and his supporters (some local Armenian merchants and the family of the ex-Prime Minister Lónyay Menyhért (1822–1884) tried to bribe the voters by means of bank checks instead of the usual cash in hand, Mara’s electoral agents redeemed to the villagers the bank checks’ value in cash and with this, he won the elections by making use mostly of his opponent’s money and supported by the supposedly nationally entrenched Romanians. At the time (1881), the story made its way in the regional and central newspapers, which might be the original source of Mikszáth’s story. Three years later, on the eve of a new election, a delegation of Romanian voters came to see their representative. He greeted them and asked about their wishes and requests for the upcoming elections, only to find out that they were humbly asking him to provide… a counter-candidate. When the mesmerized deputy asked for the purpose of such a request, the villagers’ leader replied: “…well, to have some joy in the district.” The trope of the voters asking for a counter-candidate mainly for the purpose of raising the stake of the electoral bribe is rather frequent in the time’s literature and press, here however it was used for underlining the connection between a local patron and his pool of voters. In Mikszáth’s story, Mara granted them this wish too. Historical sources show that Mara went on for another mandate, with the counter-candidate (Kemény Miklós) only getting seven votes.

As all literary sources, Mikszáth’s story was probably built around a grain of truth, despite the author’s inevitable fictional contribution. The story sheds some light not only on the voting practices of the time, but also on the voters’ expectations (i.e. the electoral campaign as a moment of feast and joy) and on the paternalistic relations enhanced by political needs.

One of his sons, also bearing the name Lőrinc, was an architect. He was married to Berta Zalandak.

Another son, László Mara, was Lord Lieutenant of Hunyad County during the First World War. In this capacity, he intervened for the liberation of a Romanian lawyer and reserve officer named Gheorghe Dubleșiu, who was imprisoned due to his nationalist rhetoric. A few years later, under the Romanian rule, Gheorghe Dubleșiu would become Prefect (i.e., Lord Lieutenant) of the Hunyad County in 1920 and between 1922–1926.

Sources:

Press

“A Hon”, XIX, 1881, 6 July, no. 184.

“Magyar Polgár”, XV, 1881, 5 July, no. 150, p. 1;

Literature

Mikszáth Kálmán, “Összes műve. Cikkek és karcolatok (51–86. kötet). 1883 Parlamenti karcolatok (68. kötet). A t. házból [márc. 9.]. IV. A Mara Lőrinc emberei”, electronic edition on https://www.arcanum.hu;

Lajos Kelemen, A felsőszálláspataki Marák családi krónikája, Genealógiai Füzetek, 1912, pp. 97-10;

József Szinnyei, “Magyar írók élete és munkái”, electronic edition on https://www.arcanum.hu.

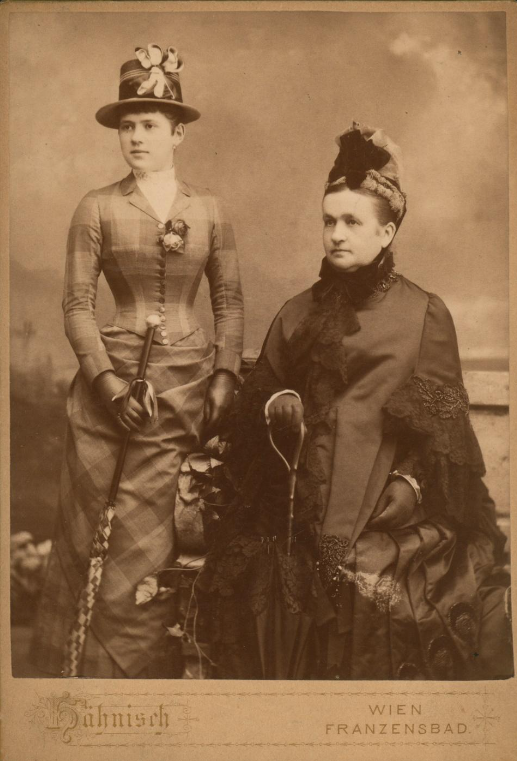

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.

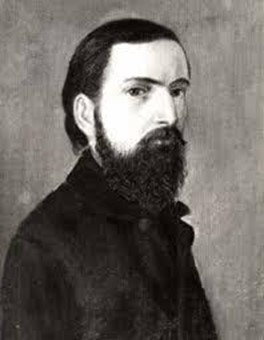

Count Manó (Emánuel) Péchy (1813–1889)

The Péchy family received the noble charter from Ferdinand I. at the beginning of the 16th century. The extended family held important positions in Sáros county, several of them were county commissioners (alispán), but later they also spread to other counties. The MP’s father József Péchy was a landowner in Abaúj-Torna county, and for his financial help in the Napoleonic Wars he was awarded the title of count in the early 19th century (1810). So when Emánuel / Manó Péchy was born in 1813 in the family castle in Boldogkőváralja, Abaúj county, the ink was barely dry on his father’s aristocratic rank.

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Emánuel (Manó) Péchy

Péchy passed the bar exam in 1834, after studying law at the Academy of Law in Košice (Kassa). In the 1839–40 Diet he became a representative of Abaúj county, after having been vice- and then chief county notary for a short time. His loyal attitude in the Diet probably contributed to the fact that at the end of 1841 Archduke Joseph (1776–1847), the Palatine of Hungary, appointed him as the administrator of the Zemplén county, which was adjacent to Abaúj. However, Péchy’s early career was interrupted by the revolution of 1848.

In 1844 he married Baroness Zenaida Meskó (1828–1861), the younger daughter of Baron Jakab Meskó and Count Anna Fáy. The Meskó sisters were considered a very good party, because in the absence of a male heir, they inherited the entire family fortune. It seems that the older sister, Irén, was intended for Péchy first. We do not know the reason why this marriage failed, but the fact is that in 1843 Irén married count Henrik Zichy (1812–1892), while Péchy married the younger sister Zenaida a year later. His only brother Konstantin (1821–1866), who was an officer in the army, was married to Count Irma Forgách (1822–1872), also from an aristocratic family in the area.

Although conservative, Péchy did not take office during the years of neo-absolutism; he retired to his estate to wait for better times. Following the October Diploma (1860), the Hungarian counties were restored. Péchy was appointed as the Lord-Lieutenant of Abaúj county and the city of Košice (Kassa). The following year, however, he resigned, as did most of the Lord-Lieutenants. The new Chancellor count Herman Zichy (1814–1892) was the brother of Péchy’s brother-in-law Henrik Zichy.

In 1865, as a prelude to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, new Lord-Lieutenants were partly appointed and parlty reinstated, including Péchy, as the head of Abaúj county and Košice. However, his career took a new direction after the Compromise. At that time, he was appointed Royal Commissioner for Transylvania, with the task of overseeing the integration of Transylvania, advising the Hungarian government and reducing ethnic tensions. His appointment was initiated by the Prime Minister, Gyula Andrássy (1823–1890), with whom they had known each other since Péchy was the county administrator of Zemplén County.

After the abolition of the royal commissioner’s office (1872), Péchy’s ties with Transylvania loosened, if not completely disappeared. From 1872 he was a member of the Parliament of Cluj (Kolozsvár) for three terms. Subsequently, in 1881, he was elected in Košice, where he began his political career. His name came up a few times in political combinations: as Minister of the Interior and, in 1879, as Minister of Finance. But no further political role awaited him. The elderly Péchy was a member of the upper house of parliament.

In his private life he suffered many adversities. Several of his children died in infancy and his only son was killed in an accident when he was ten. His wife never recovered from this loss, and died in 1861 after a long illness. He did not remarry after his wife’s death, although there are several hints of his gallant adventures. Perhaps the most controversial was his affair with a young actress in Košice, Lujza Nagy (1843–1911). His only daughter Jaqueline Péchy (1846–1915) was brought up by his brother-in-law Henrik Zichy in Moson County until she married Henrik’s younger brother Rudolf (1833–1893) – stepson of the famous Hungarian politician István Széchenyi (1791–1860) – in 1864. Jaqueline had seven children, but she was unable to see her younger children because she became blind at a young age.

Manó Péchy even lived to see one of his grandchildren, Eleonóra Zichy (1867–1945), marry the son of the former Prime Minister and later Foreign Minister of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Gyula Andrássy, Tivadar (1857–1905) (and after his death to his other son Gyula Andrássy Jr., 1860–1929). Katinka Andrássy (1892–1985), the great-granddaughter of Manó Péchy, one of the couple’s daughters, became famous as the “Red Countess”. She was the wife of Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955), the Prime Minister and later President of the Republic who came to power in 1918 after the so-called Aster Revolution.

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Eleónora Andrássy (1867–1945)

Manó Péchy died in the summer of 1889 in Boldogkőváralján, in his family castle.

Boldogkőváralján residence Boldogkőváralján castle

Bibliography

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Aristokrat v službách štátu. Gróf Emanuel Péchy, Bratislava, Kalligram, 2006.

Judit Pál, Unió vagy „unificáltatás”? Erdély uniója és a királyi biztos működése (1867–1872) (Union or "unification"? The Union of Transylvania and the functioning of the Royal Commissioner). Kolozsvár, Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2010.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Emanuel Péchy ako župan Abova a Košíc. In: Historica Carpatica. Zborník Východoslovenského Múzea v Košíciach 35 (2004). Vydalo Východoslovenské múzeum v Košiciach, 2004, pp. 55–72.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Štyri stretnutia a dve kariéry (gróf Gyula Andrássy a gróf Emanuel Péchy). In: Acta Historica Historica Neosolensia, tomus 9, Banská Bystrica, Katedra histórie FHV Univerzity Mateja Bela, 2006, pp. 65–80.

Judit Pál, Péchy Manó – a „mintahivatalnok” (Manó Péchy the „model official”). Erdélyi Múzeum. LXIX. (2007) no. 1–2, pp. 33–61.

Judit Pál – Roman Holec, Gróf Emanuel Péchy ako kráľovský komisár Sedmohradska (1867–1872). In: Historické štúdie. roč. 45 (Bratislava, 2007), pp. 169–203.

Roman Holec – Judit Pál, Dvaja vysokí štátni úradníci – dva integračné pokusy – dve „imperiálne kariéry“? (knieža Karl Schwarzenberg a gróf Emanuel Péchy v Sedmohradsku). Historický časopis, vol. 62 (2014) nr. 3. pp. 447−470.

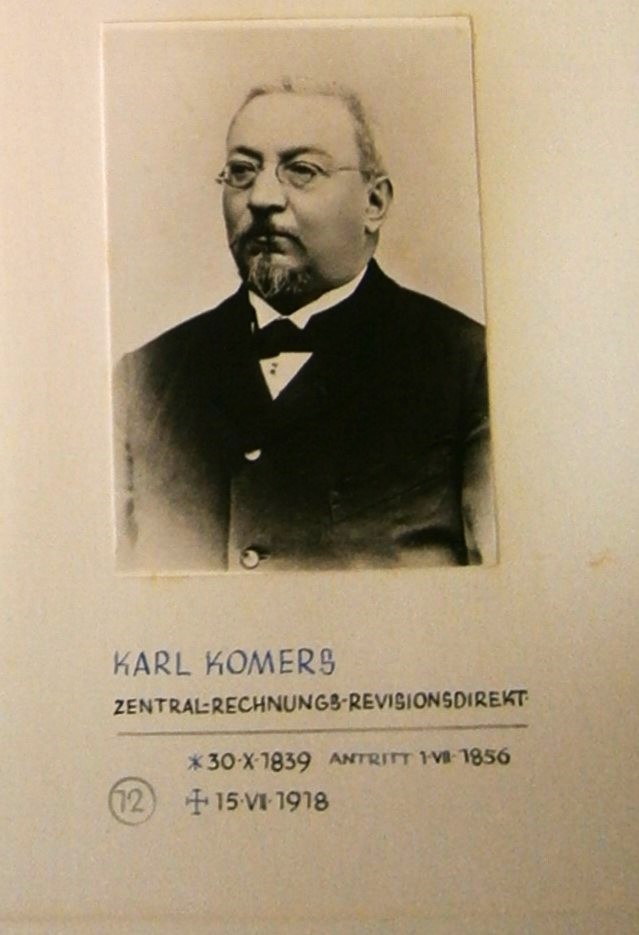

Brothers Aleš (17 July 1852 – 9 September 1909) and Karel Komers (30 October 1839 – 15 July 1918) – career of a state and a private official

The new structure of public administration in the middle of the 19th century introduced administrative dualism: firstly, there were the state political authorities, with their competences, and secondly, the newly established local government bodies. In Bohemia (as well as in Moravia and Silesia), political districts were gradually established, administered by district captainships headed by a district captain. In parallel, in Bohemia there was the local self-governing administration consisting of district authorities led by a district mayor. As concerns patrimonial administration, it was partly taken over by the local authorities. What remained was private administration of large estates. The extensive public agenda needed qualified staff and offered employment in a number of clerical and office jobs. Work in the public administration offered a regular salary, and after a certain time also the guarantee of a pay rise as well as the opportunity to climb the career ladder and achieve social prestige. Private administration of large estates adapted the principles of state administration to suit its own needs, but the internal administrative setup always depended on the owner of the estate. Nevertheless, even private officials could rely on receiving a regular salary, sometimes also accompanied by numerous benefits, and the chance of career advancement linked to social prestige and titles. On the other hand, both public and private service required frequent moving for work.

For many graduates of secondary schools, gymnasiums and universities, a career in the civil service meant leaving their hometown and family tradition. Not all siblings in a family were always able to study. Some completed only the basic education needed to take over a farm or a trade. Those parents who let their children study, very often, alongside church or military careers, sent them to study to become teachers or doctors, or the children found employment in public or private administration. In several of the families studied in this project, one of the brothers was employed in the civil service and one in the private sector, thus giving us the possibility to compare their life stories: their careers, their salaries and the highest position attained, as well as their family background (entry into marriage, number of children).

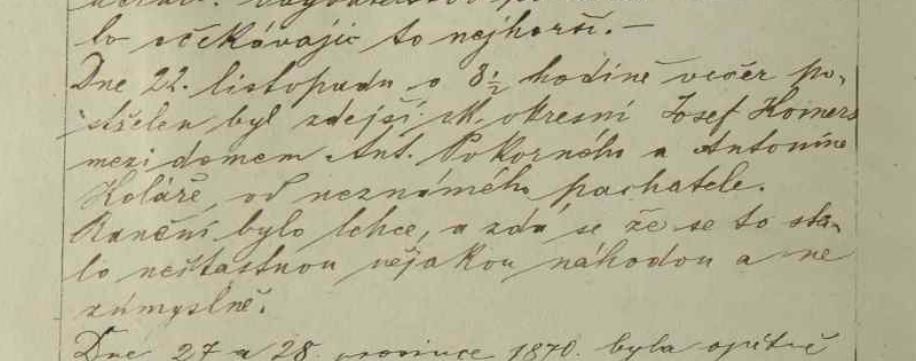

Josef Komers (1809–1876), father of the brothers Aleš and Karel, came from a large family of craftsmen from Humpolec. He was raised together with his seventeen siblings (both his full and half-siblings) in a family of butchers. Of his siblings, only one (half) brother survived to adulthood; he stayed in Humpolec and worked as a confectioner and gingerbread baker. Five of Josef’s sisters married woollen cloth makers and dyers. Josef was the only one who at the age of 16 abandoned the tradition of crafts and went into traineeship on an estate, where he later became a financial and administrative clerk. He left the patrimonial service in 1838, when he obtained the position as a clerk at the municipal office in Mšeno, Central Bohemia. Josef Komers then spent the rest of his professional career working in various offices of the political administration. In 1870, while working as a district commissioner in Milevsko, a terrible thing happened to him: he was shot. Reports detailing his injury immediately appeared in the press, but the wound was not serious after all. The chronicle of Milevsko notes the following about the incident: “(...) he suffered just a minor injury, and the shooting seems to have been accidental and not intentional.” Josef Komers remained in the position of district captain in Milevsko until 1875, when he retired. He died a few months later in Smíchov. The press reported on his death, recalling that he “enjoyed universal esteem everywhere and won the hearts of people.” Josef Komers was the first member of his family to work in administrative offices, and his sons followed in his footsteps.

Report of the shooting from the Milevsko Chronicle

Josef Komers married Johanna Kozlíková (1820–1893), the daughter of a furrier from Mšeno in Central Bohemia. The couple had a total of nine children, of whom four daughters and two sons lived to adulthood. Both sons received an education and held office positions, the elder Karel in the private princely economic administration of a large estate, the younger Aleš in the state political administration.

Karel (whose full name was Karel Boromeus Marcel) was born on 30 October 1839 in Mšeno as the first-born son of the municipal clerk Josef Komers. He graduated from a Prague grammar school and then took up a traineeship at the district office in Hlinsko, where his father Josef was an assistant clerk at the time. The trainees usually performed their traineeship at their own expense and very often worked as assistants to their fathers or other relatives. However, Karel Komers soon decided to leave the political administration and in November 1857 he was hired as a trainee in the economic administration at the estate of Nasavrky, belonging to the princely Auersperg family. He then spent the next 56 years in the service of the Princes of Auersperg.

Karel’s traineeship period, i.e. his training and becoming familiar with everyday office work, ended in August 1862, when he became an economic assistant clerk of the second class and was transferred to the administrative office of the Auersperg estate of Nieder Fladnitz in Lower Austria. In May 1871 he was promoted to the position of economic controller. Further career advancement soon followed. In 1874, he returned to Bohemia and became an assistant at the Auersperg Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1879, i.e. more than sixteen years after entering the service, he became an accounting auditor. In the civil administration, such a position would have been equivalent to the rank IX and to the position of, for example, district commissioner. By a decree of 28 December 1878, Karel Komers also obtained a rise in salary, his annual monetary remuneration amounting to 1 600 guldens, which would have corresponded to the rank VIII in the civil service.

Aleš (whose full name was Aleš Josef) was born on 17 July 1852 in Hlinsko. At the time, his father was a local district commissioner of the second class. Unlike his father and brother, Aleš graduated from the Faculty of Law at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. Legal education was a prerequisite for a career in political administration. Aleš Komers started in 1874 as a trainee official at the Bohemian Governor’s Office and three years later became a junior governor’s office official. As early as 1879, Aleš Komers was appointed a district commissioner. He thus reached the same position as his brother after about two years (not counting the time as a trainee).

Karel Komers continued his career at the Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1885 he was appointed chief auditor and remained in this position for more than twenty-eight years. From January 1914 he held the post of Director of the Central Audit Office with an annual salary of 6 000 crowns and in-kind benefits. The same princely decree granted the same amount of salary also to Vincenz Kern, the central treasurer in Vienna, to Josef Valenta, the director of the mining office and a chemical factory, to Martin Höcher, the director of a sugar mill in Slatiňany, and to Wenzl Hruška, the director of a Slatiňany estate. These positions would have corresponded to approximately rank VIII–VII in the civil service. In terms of financial remuneration, the aforementioned salary of 6 000 crowns would have corresponded to the salary of a district captain according to Act No. 34/1907. Karel Komers remained in the position of Director of the Central Audit Office until his death in July 1918.

Aleš Komers reached the peak of his career in 1890, when he became a district captain in the rank VII. He remained in this position until his death in 1909. In 1899 he was given the title of junior governor’s office councillor, which corresponded to the rank VI. At that time his salary could range from 6 400 crowns upwards.

When comparing the careers of both brothers, it is remarkable to observe the point at which their careers intersected in 1879. In that year, both had attained roughly the same position, corresponding to the rank IX: Karel was promoted to accounting auditor while Aleš was appointed district commissioner. It is also worth mentioning that it was in the position of district commissioner that their father Josef died in 1876. What differs substantially, however, is the time that it took the two brothers to reach their respective positions. Karel spent more than sixteen years (and four and a half years of traineeship) in the princely service, while his younger brother Aleš, who had a law degree, reached his position after only two years (and three years of traineeship). University education played a crucial role in this respect, but it is also evident that a long and loyal service, in itself a condition for attaining higher positions, was appreciated in the private sphere.

The families of the two brothers were also quite similar. For both of them, the wives they chose were a confirmation of the social status they had attained. In May 1871, Karel Komers married Terezie (1845–1922), the daughter of the late Albert Pudivitr, former princely administrator of the Nieder Fladnitz estate. The couple had three children, two sons and a daughter. In 1874 their son Aleš (Alexius) was born, who later became district captain and ministerial councillor ad personam. In 1883, Karel’s brother Aleš Komers married Marie (1861–1920), the daughter of the provincial lawyer and notary Eduard Brzorád. Aleš and his wife also had three children, two sons and a daughter, but both sons died; Eduard a few months after his birth, and Aleš, a medical student, shot himself at the age of nineteen. Both Komers brothers started their families at the ages of 30 (31), and both had three children, the last being born when they were 39 years old.

Archival sources:

Archival Department of Zámrsk, Nasavrky Estate: Knihy výnosů a nařízení 1900–1923, Personalstand 1840–1897.

State Regional Archive of Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the East Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Hlinsko

State Regional Archive of Prague, Collection of registers of the Central Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Mšeno

State District Archive of Písek, Archive of the town of Milevsko, Memorabilienbuch der Stadt Mühlhausen.

Selected literature:

HLEDÍKOVÁ, Zdeňka, JANÁK, Jan a DOBEŠ, Jan. Dějiny správy v českých zemích: od počátků státu po současnost. Praha: NLN, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, 2005.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin. Poslušný vládce okresu: okresní hejtman a proměny státní moci v Čechách v letech 1868-1938. Praha: NLN, 2021.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin a kol. Slovník představitelů politické správy v Čechách v letech 1849-1918. Praha: Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR, v.v.i., 2020.

VYSKOČIL, Aleš. C. k. úředník ve zlatém věku jistoty. Praha: Historický ústav, 2009.

Ottův slovník naučný. Sedmý díl. Praha: J. Otto, 1893, p. 501–502.

Newspaper articles:

Pražský denník, 1876 (15 March)

Pokrok, 1870 (25 November)

Brothers Aleš (17 July 1852 – 9 September 1909) and Karel Komers (30 October 1839 – 15 July 1918) – career of a state and a private official

The new structure of public administration in the middle of the 19th century introduced administrative dualism: firstly, there were the state political authorities, with their competences, and secondly, the newly established local government bodies. In Bohemia (as well as in Moravia and Silesia), political districts were gradually established, administered by district captainships headed by a district captain. In parallel, in Bohemia there was the local self-governing administration consisting of district authorities led by a district mayor. As concerns patrimonial administration, it was partly taken over by the local authorities. What remained was private administration of large estates. The extensive public agenda needed qualified staff and offered employment in a number of clerical and office jobs. Work in the public administration offered a regular salary, and after a certain time also the guarantee of a pay rise as well as the opportunity to climb the career ladder and achieve social prestige. Private administration of large estates adapted the principles of state administration to suit its own needs, but the internal administrative setup always depended on the owner of the estate. Nevertheless, even private officials could rely on receiving a regular salary, sometimes also accompanied by numerous benefits, and the chance of career advancement linked to social prestige and titles. On the other hand, both public and private service required frequent moving for work.

For many graduates of secondary schools, gymnasiums and universities, a career in the civil service meant leaving their hometown and family tradition. Not all siblings in a family were always able to study. Some completed only the basic education needed to take over a farm or a trade. Those parents who let their children study, very often, alongside church or military careers, sent them to study to become teachers or doctors, or the children found employment in public or private administration. In several of the families studied in this project, one of the brothers was employed in the civil service and one in the private sector, thus giving us the possibility to compare their life stories: their careers, their salaries and the highest position attained, as well as their family background (entry into marriage, number of children).

Josef Komers (1809–1876), father of the brothers Aleš and Karel, came from a large family of craftsmen from Humpolec. He was raised together with his seventeen siblings (both his full and half-siblings) in a family of butchers. Of his siblings, only one (half) brother survived to adulthood; he stayed in Humpolec and worked as a confectioner and gingerbread baker. Five of Josef’s sisters married woollen cloth makers and dyers. Josef was the only one who at the age of 16 abandoned the tradition of crafts and went into traineeship on an estate, where he later became a financial and administrative clerk. He left the patrimonial service in 1838, when he obtained the position as a clerk at the municipal office in Mšeno, Central Bohemia. Josef Komers then spent the rest of his professional career working in various offices of the political administration. In 1870, while working as a district commissioner in Milevsko, a terrible thing happened to him: he was shot. Reports detailing his injury immediately appeared in the press, but the wound was not serious after all. The chronicle of Milevsko notes the following about the incident: “(...) he suffered just a minor injury, and the shooting seems to have been accidental and not intentional.” Josef Komers remained in the position of district captain in Milevsko until 1875, when he retired. He died a few months later in Smíchov. The press reported on his death, recalling that he “enjoyed universal esteem everywhere and won the hearts of people.” Josef Komers was the first member of his family to work in administrative offices, and his sons followed in his footsteps.

Report of the shooting from the Milevsko Chronicle

Josef Komers married Johanna Kozlíková (1820–1893), the daughter of a furrier from Mšeno in Central Bohemia. The couple had a total of nine children, of whom four daughters and two sons lived to adulthood. Both sons received an education and held office positions, the elder Karel in the private princely economic administration of a large estate, the younger Aleš in the state political administration.

Karel (whose full name was Karel Boromeus Marcel) was born on 30 October 1839 in Mšeno as the first-born son of the municipal clerk Josef Komers. He graduated from a Prague grammar school and then took up a traineeship at the district office in Hlinsko, where his father Josef was an assistant clerk at the time. The trainees usually performed their traineeship at their own expense and very often worked as assistants to their fathers or other relatives. However, Karel Komers soon decided to leave the political administration and in November 1857 he was hired as a trainee in the economic administration at the estate of Nasavrky, belonging to the princely Auersperg family. He then spent the next 56 years in the service of the Princes of Auersperg.

Karel’s traineeship period, i.e. his training and becoming familiar with everyday office work, ended in August 1862, when he became an economic assistant clerk of the second class and was transferred to the administrative office of the Auersperg estate of Nieder Fladnitz in Lower Austria. In May 1871 he was promoted to the position of economic controller. Further career advancement soon followed. In 1874, he returned to Bohemia and became an assistant at the Auersperg Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1879, i.e. more than sixteen years after entering the service, he became an accounting auditor. In the civil administration, such a position would have been equivalent to the rank IX and to the position of, for example, district commissioner. By a decree of 28 December 1878, Karel Komers also obtained a rise in salary, his annual monetary remuneration amounting to 1 600 guldens, which would have corresponded to the rank VIII in the civil service.

Aleš (whose full name was Aleš Josef) was born on 17 July 1852 in Hlinsko. At the time, his father was a local district commissioner of the second class. Unlike his father and brother, Aleš graduated from the Faculty of Law at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. Legal education was a prerequisite for a career in political administration. Aleš Komers started in 1874 as a trainee official at the Bohemian Governor’s Office and three years later became a junior governor’s office official. As early as 1879, Aleš Komers was appointed a district commissioner. He thus reached the same position as his brother after about two years (not counting the time as a trainee).

Karel Komers continued his career at the Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1885 he was appointed chief auditor and remained in this position for more than twenty-eight years. From January 1914 he held the post of Director of the Central Audit Office with an annual salary of 6 000 crowns and in-kind benefits. The same princely decree granted the same amount of salary also to Vincenz Kern, the central treasurer in Vienna, to Josef Valenta, the director of the mining office and a chemical factory, to Martin Höcher, the director of a sugar mill in Slatiňany, and to Wenzl Hruška, the director of a Slatiňany estate. These positions would have corresponded to approximately rank VIII–VII in the civil service. In terms of financial remuneration, the aforementioned salary of 6 000 crowns would have corresponded to the salary of a district captain according to Act No. 34/1907. Karel Komers remained in the position of Director of the Central Audit Office until his death in July 1918.

Aleš Komers reached the peak of his career in 1890, when he became a district captain in the rank VII. He remained in this position until his death in 1909. In 1899 he was given the title of junior governor’s office councillor, which corresponded to the rank VI. At that time his salary could range from 6 400 crowns upwards.

When comparing the careers of both brothers, it is remarkable to observe the point at which their careers intersected in 1879. In that year, both had attained roughly the same position, corresponding to the rank IX: Karel was promoted to accounting auditor while Aleš was appointed district commissioner. It is also worth mentioning that it was in the position of district commissioner that their father Josef died in 1876. What differs substantially, however, is the time that it took the two brothers to reach their respective positions. Karel spent more than sixteen years (and four and a half years of traineeship) in the princely service, while his younger brother Aleš, who had a law degree, reached his position after only two years (and three years of traineeship). University education played a crucial role in this respect, but it is also evident that a long and loyal service, in itself a condition for attaining higher positions, was appreciated in the private sphere.

The families of the two brothers were also quite similar. For both of them, the wives they chose were a confirmation of the social status they had attained. In May 1871, Karel Komers married Terezie (1845–1922), the daughter of the late Albert Pudivitr, former princely administrator of the Nieder Fladnitz estate. The couple had three children, two sons and a daughter. In 1874 their son Aleš (Alexius) was born, who later became district captain and ministerial councillor ad personam. In 1883, Karel’s brother Aleš Komers married Marie (1861–1920), the daughter of the provincial lawyer and notary Eduard Brzorád. Aleš and his wife also had three children, two sons and a daughter, but both sons died; Eduard a few months after his birth, and Aleš, a medical student, shot himself at the age of nineteen. Both Komers brothers started their families at the ages of 30 (31), and both had three children, the last being born when they were 39 years old.

Archival sources:

Archival Department of Zámrsk, Nasavrky Estate: Knihy výnosů a nařízení 1900–1923, Personalstand 1840–1897.

State Regional Archive of Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the East Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Hlinsko

State Regional Archive of Prague, Collection of registers of the Central Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Mšeno

State District Archive of Písek, Archive of the town of Milevsko, Memorabilienbuch der Stadt Mühlhausen.

Selected literature:

HLEDÍKOVÁ, Zdeňka, JANÁK, Jan a DOBEŠ, Jan. Dějiny správy v českých zemích: od počátků státu po současnost. Praha: NLN, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, 2005.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin. Poslušný vládce okresu: okresní hejtman a proměny státní moci v Čechách v letech 1868-1938. Praha: NLN, 2021.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin a kol. Slovník představitelů politické správy v Čechách v letech 1849-1918. Praha: Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR, v.v.i., 2020.

VYSKOČIL, Aleš. C. k. úředník ve zlatém věku jistoty. Praha: Historický ústav, 2009.

Ottův slovník naučný. Sedmý díl. Praha: J. Otto, 1893, p. 501–502.

Newspaper articles:

Pražský denník, 1876 (15 March)

Pokrok, 1870 (25 November)

Brothers Aleš (17 July 1852 – 9 September 1909) and Karel Komers (30 October 1839 – 15 July 1918) – career of a state and a private official

The new structure of public administration in the middle of the 19th century introduced administrative dualism: firstly, there were the state political authorities, with their competences, and secondly, the newly established local government bodies. In Bohemia (as well as in Moravia and Silesia), political districts were gradually established, administered by district captainships headed by a district captain. In parallel, in Bohemia there was the local self-governing administration consisting of district authorities led by a district mayor. As concerns patrimonial administration, it was partly taken over by the local authorities. What remained was private administration of large estates. The extensive public agenda needed qualified staff and offered employment in a number of clerical and office jobs. Work in the public administration offered a regular salary, and after a certain time also the guarantee of a pay rise as well as the opportunity to climb the career ladder and achieve social prestige. Private administration of large estates adapted the principles of state administration to suit its own needs, but the internal administrative setup always depended on the owner of the estate. Nevertheless, even private officials could rely on receiving a regular salary, sometimes also accompanied by numerous benefits, and the chance of career advancement linked to social prestige and titles. On the other hand, both public and private service required frequent moving for work.

For many graduates of secondary schools, gymnasiums and universities, a career in the civil service meant leaving their hometown and family tradition. Not all siblings in a family were always able to study. Some completed only the basic education needed to take over a farm or a trade. Those parents who let their children study, very often, alongside church or military careers, sent them to study to become teachers or doctors, or the children found employment in public or private administration. In several of the families studied in this project, one of the brothers was employed in the civil service and one in the private sector, thus giving us the possibility to compare their life stories: their careers, their salaries and the highest position attained, as well as their family background (entry into marriage, number of children).

Josef Komers (1809–1876), father of the brothers Aleš and Karel, came from a large family of craftsmen from Humpolec. He was raised together with his seventeen siblings (both his full and half-siblings) in a family of butchers. Of his siblings, only one (half) brother survived to adulthood; he stayed in Humpolec and worked as a confectioner and gingerbread baker. Five of Josef’s sisters married woollen cloth makers and dyers. Josef was the only one who at the age of 16 abandoned the tradition of crafts and went into traineeship on an estate, where he later became a financial and administrative clerk. He left the patrimonial service in 1838, when he obtained the position as a clerk at the municipal office in Mšeno, Central Bohemia. Josef Komers then spent the rest of his professional career working in various offices of the political administration. In 1870, while working as a district commissioner in Milevsko, a terrible thing happened to him: he was shot. Reports detailing his injury immediately appeared in the press, but the wound was not serious after all. The chronicle of Milevsko notes the following about the incident: “(...) he suffered just a minor injury, and the shooting seems to have been accidental and not intentional.” Josef Komers remained in the position of district captain in Milevsko until 1875, when he retired. He died a few months later in Smíchov. The press reported on his death, recalling that he “enjoyed universal esteem everywhere and won the hearts of people.” Josef Komers was the first member of his family to work in administrative offices, and his sons followed in his footsteps.

Report of the shooting from the Milevsko Chronicle

Josef Komers married Johanna Kozlíková (1820–1893), the daughter of a furrier from Mšeno in Central Bohemia. The couple had a total of nine children, of whom four daughters and two sons lived to adulthood. Both sons received an education and held office positions, the elder Karel in the private princely economic administration of a large estate, the younger Aleš in the state political administration.

Karel (whose full name was Karel Boromeus Marcel) was born on 30 October 1839 in Mšeno as the first-born son of the municipal clerk Josef Komers. He graduated from a Prague grammar school and then took up a traineeship at the district office in Hlinsko, where his father Josef was an assistant clerk at the time. The trainees usually performed their traineeship at their own expense and very often worked as assistants to their fathers or other relatives. However, Karel Komers soon decided to leave the political administration and in November 1857 he was hired as a trainee in the economic administration at the estate of Nasavrky, belonging to the princely Auersperg family. He then spent the next 56 years in the service of the Princes of Auersperg.

Karel’s traineeship period, i.e. his training and becoming familiar with everyday office work, ended in August 1862, when he became an economic assistant clerk of the second class and was transferred to the administrative office of the Auersperg estate of Nieder Fladnitz in Lower Austria. In May 1871 he was promoted to the position of economic controller. Further career advancement soon followed. In 1874, he returned to Bohemia and became an assistant at the Auersperg Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1879, i.e. more than sixteen years after entering the service, he became an accounting auditor. In the civil administration, such a position would have been equivalent to the rank IX and to the position of, for example, district commissioner. By a decree of 28 December 1878, Karel Komers also obtained a rise in salary, his annual monetary remuneration amounting to 1 600 guldens, which would have corresponded to the rank VIII in the civil service.

Aleš (whose full name was Aleš Josef) was born on 17 July 1852 in Hlinsko. At the time, his father was a local district commissioner of the second class. Unlike his father and brother, Aleš graduated from the Faculty of Law at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. Legal education was a prerequisite for a career in political administration. Aleš Komers started in 1874 as a trainee official at the Bohemian Governor’s Office and three years later became a junior governor’s office official. As early as 1879, Aleš Komers was appointed a district commissioner. He thus reached the same position as his brother after about two years (not counting the time as a trainee).

Karel Komers continued his career at the Central Audit Office in Tupadly. In 1885 he was appointed chief auditor and remained in this position for more than twenty-eight years. From January 1914 he held the post of Director of the Central Audit Office with an annual salary of 6 000 crowns and in-kind benefits. The same princely decree granted the same amount of salary also to Vincenz Kern, the central treasurer in Vienna, to Josef Valenta, the director of the mining office and a chemical factory, to Martin Höcher, the director of a sugar mill in Slatiňany, and to Wenzl Hruška, the director of a Slatiňany estate. These positions would have corresponded to approximately rank VIII–VII in the civil service. In terms of financial remuneration, the aforementioned salary of 6 000 crowns would have corresponded to the salary of a district captain according to Act No. 34/1907. Karel Komers remained in the position of Director of the Central Audit Office until his death in July 1918.

Aleš Komers reached the peak of his career in 1890, when he became a district captain in the rank VII. He remained in this position until his death in 1909. In 1899 he was given the title of junior governor’s office councillor, which corresponded to the rank VI. At that time his salary could range from 6 400 crowns upwards.

When comparing the careers of both brothers, it is remarkable to observe the point at which their careers intersected in 1879. In that year, both had attained roughly the same position, corresponding to the rank IX: Karel was promoted to accounting auditor while Aleš was appointed district commissioner. It is also worth mentioning that it was in the position of district commissioner that their father Josef died in 1876. What differs substantially, however, is the time that it took the two brothers to reach their respective positions. Karel spent more than sixteen years (and four and a half years of traineeship) in the princely service, while his younger brother Aleš, who had a law degree, reached his position after only two years (and three years of traineeship). University education played a crucial role in this respect, but it is also evident that a long and loyal service, in itself a condition for attaining higher positions, was appreciated in the private sphere.

The families of the two brothers were also quite similar. For both of them, the wives they chose were a confirmation of the social status they had attained. In May 1871, Karel Komers married Terezie (1845–1922), the daughter of the late Albert Pudivitr, former princely administrator of the Nieder Fladnitz estate. The couple had three children, two sons and a daughter. In 1874 their son Aleš (Alexius) was born, who later became district captain and ministerial councillor ad personam. In 1883, Karel’s brother Aleš Komers married Marie (1861–1920), the daughter of the provincial lawyer and notary Eduard Brzorád. Aleš and his wife also had three children, two sons and a daughter, but both sons died; Eduard a few months after his birth, and Aleš, a medical student, shot himself at the age of nineteen. Both Komers brothers started their families at the ages of 30 (31), and both had three children, the last being born when they were 39 years old.

Archival sources:

Archival Department of Zámrsk, Nasavrky Estate: Knihy výnosů a nařízení 1900–1923, Personalstand 1840–1897.

State Regional Archive of Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the East Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Hlinsko

State Regional Archive of Prague, Collection of registers of the Central Bohemian region, Parish office of the Roman Catholic Church in Mšeno

State District Archive of Písek, Archive of the town of Milevsko, Memorabilienbuch der Stadt Mühlhausen.

Selected literature:

HLEDÍKOVÁ, Zdeňka, JANÁK, Jan a DOBEŠ, Jan. Dějiny správy v českých zemích: od počátků státu po současnost. Praha: NLN, Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, 2005.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin. Poslušný vládce okresu: okresní hejtman a proměny státní moci v Čechách v letech 1868-1938. Praha: NLN, 2021.

KLEČACKÝ, Martin a kol. Slovník představitelů politické správy v Čechách v letech 1849-1918. Praha: Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR, v.v.i., 2020.

VYSKOČIL, Aleš. C. k. úředník ve zlatém věku jistoty. Praha: Historický ústav, 2009.

Ottův slovník naučný. Sedmý díl. Praha: J. Otto, 1893, p. 501–502.

Newspaper articles:

Pražský denník, 1876 (15 March)

Pokrok, 1870 (25 November)