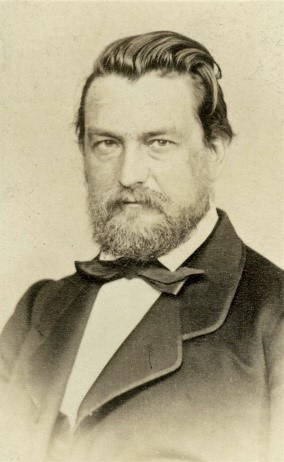

Maximilian Obentraut (1795–1883). A mysterious origin of a County President

In the modern society of the 19th century, illegitimate origin was still one of the most painful social stigmas that an individual could bring with him or her into life. The absence of a father, the precariousness of the family background, usually combined with a lack of financial resources and the difficulty securing the livelihood for the mother and child did not offer very good prospects for the individual’s social position, provided he or she lived to adulthood at all. In addition, there were various restrictions concerning studies, scholarships or admission to the civil service, which required the submission of a baptismal certificate and which immediately made it clear what background the applicant came from. In this respect, illegitimate children of the higher social classes represented a certain exception. Although illegitimacy in the milieu of the royal court and the aristocracy was no less undesirable from the point of view of the Church than it was for the general population, the range of possibilities for taking care of an illegitimate child was much wider. Moreover, conceiving and giving birth to a child out of wedlock was decriminalised by the Enlightenment reforms, and in this regard, demographers speak of the first sexual revolution, when baptismal registers began to be filled with children for whom the slot for the father’s name remained empty.

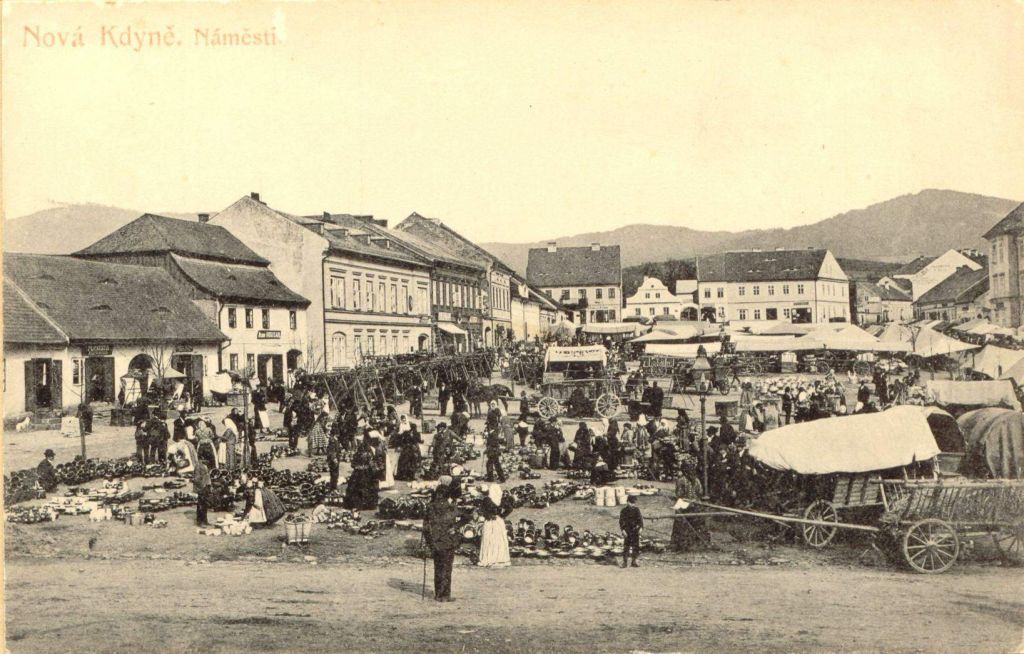

Maximilian Obentraut was born as an illegitimate child under dramatic circumstances on 12 October 1795, in a coaching inn on the square of the West Bohemian town of Kdyně/Neugedein. The baptismal register says very little on his birth, the father of the child is missing and the mother is given as a certain Anna, daughter of the chief estate administrator František Obentraut from Mnichovo Hradiště/Münchengrätz. However, this is obviously a fictitious name since no such official can be traced in the archival sources. The later brilliant career of Maximilian (named after his patron saint on the day of his birth) as a civil servant gave rise to a whole range of conjectures and speculations about his origin, and even became the subject of a fictional story by the local writer and Catholic priest Jindřich Šimon Baar (1869–1925). In his novel Lůzy, he vividly describes both the boy’s birth and his later upbringing and education.

We may assume that in his historical novels Baar reflected local narratives or stories which he may have heard from his fellow clergymen, and which, incidentally, can be supported by a large amount of circumstantial evidence and various strange circumstances connected with Obentraut’s origins and his civil-service career. His mother is identified by some other authors as Countess Marie Anna Stadion (1775-1841), the young wife of the former imperial ambassador Johann Philippe II Count Stadion (1763-1824), who resided at the Stadion estate in Kout/Kauth in Šumava, only a few kilometres from Kdyně. Her pregnancy during her husband’s long-term absence was obviously a serious problem that had to be kept as a secret, but during a trip to an undisclosed location – at least according to local tradition – the countess gave birth prematurely. She was forced to deliver the child unexpectedly in a country inn, but her maid insisted at least they have a private room to which only the local midwife and priest were allowed access. The next morning, the mother abandoned her child and the new-born boy was taken in by the midwife, whose son together with the inn’s waitress were his godparents at the baptism which took place at the inn still on the same day and was performed by the local priest, chaplain Martin Hufner. It was Hufner who took charge of the child afterwards, and according to Baar, the mother entrusted the child to him directly after he had confessed her and given her absolution after the birth.

The young Obentraut spent his childhood and youth in Hufner’s care and in 1798, at the age of three, he moved together with him to the nearby pilgrimage site of Tanaberk, where the Roman Catholic priest became parish priest at St. Anne’s church. Obentraut’s foster father probably also took charge of his education and subsequently supported him when Maximilian went to school in Domažlice and the Piarist grammar school in Pilsen. After graduating from the grammar school, Obentraut enrolled at the law faculty in Vienna. This seemed to be a rather unusual choice, given that he could have studied law at Prague university, where his foster father could have easily secured him a good reception among his clergy friends and from the circles of the first Czech Revivalist generation. Moving to Vienna was undoubtedly a more costly option in this respect.

Even as an illegitimate child, Maximilian Obentraut received a first-class education, thanks to his foster father’s effort to ensure that in future the orphan would find a suitable and successful employment in the society. In order not to impair the future career of the young student, it was also necessary to somehow obtain a false baptismal certificate, indicating fictitious parents: his father, Karl Obentraut, k. k. Rittmeister (captain) of the Cuirassier Regiment, and his mother, Anna, née Herold.

The freshly graduated lawyer must have probably used his fake baptismal certificate at the young age of 26 in order to enter the civil service when he became a trainee at the County Office (Kreisamt) in Mladá Boleslav/Jungbunzlau. This is where his career of a political administration official began. In February 1849, the then Interior Minister Franz Seraf Count of Stadion (1806–1853) – if we accepted the possibility that Obentraut was related to the Stadion family, Franz would have been his half-brother – nominated him for the position of county governor (Kreishauptmann) in Jičín/Gitschin. At that time, Stadion was already preparing a comprehensive reform of the public administration, which after the abolition of serfdom lost its traditional arrangement in the form of manors and magistrates of royal towns. Thus, although the former counties in their mid-18th-century form were to exist for only a few more months, by his appointment Obentraut had secured a favourable starting position in the new system. In it, he first occupied the position of one of the seven county presidents who according to Stadion’s idea of the monarchy’s organisation were to play an absolutely crucial role (even more important than the governors themselves).

With the accession of Alexander Bach to the post of Interior Minister and the promulgation of the “organic governance” by the so-called New Year’s Eve Patents (Silvesterpatente), it was obvious that a further reorganization of the structure of public administration would follow. At the time, Obentraut was appointed to the post of head of the Releasing Commission. In this position, he was in charge of the complex system of settling the serfs’ obligations and debts to their former landlords, the burden and payment of which was partly assumed by the state and its administration. In the rank of ministerial councillor, Obentraut was among the highest-ranking officials of the country, who were in direct contact with the Governor and the Minister of the Interior. Especially the Governor held him in high esteem, and so in January 1853 Obentraut was again appointed to the position of county president, this time of the key Prague region, and subsequently also to a position on the so-called organisational commission preparing the new administrative arrangement. A year later, the Emperor rewarded him for these merits with the Knight's Cross of the Order of Leopold. This decoration gave Obentraut an automatic possibility of ennoblement, which he promptly took advantage of and was knighted in 1855. Again, the ennoblement documents contained no information about his real origin or his alleged ancestors.

From the position of an illegitimate child, Maximilian Oberntraut managed to place himself among the social elite of his time. His high position within the newly established state administration was also reflected in the career opportunities of his children. Of the four sons who survived to adulthood, three graduated from the law faculty in Prague and, like their father, entered the service in the political administration. Although Maximilian after several years of practice chose a career as a notary, the other two sons remained loyal to the service of the state and the Emperor and attained equally important positions as their – illegitimate – father.

Literature

Literatura

Gustav Hofmann, Ještě k původu a životě Maxmiliána Obentrauta, Sborník Muzea Chodska v Domažlicích, 1997, pp. 18–23.

Jan Prokop Holý, „Záhadná“ osobnost rytíře Maxmiliána z Obentrautu, Zpravodaj města Horšovský Týn 2005, No. 3, p. 16.

Rudolf Šlajer, Tajemný příběh rytíře Maxmiliána, Kdyňsko 5 (2009), No. 1, p. 8

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

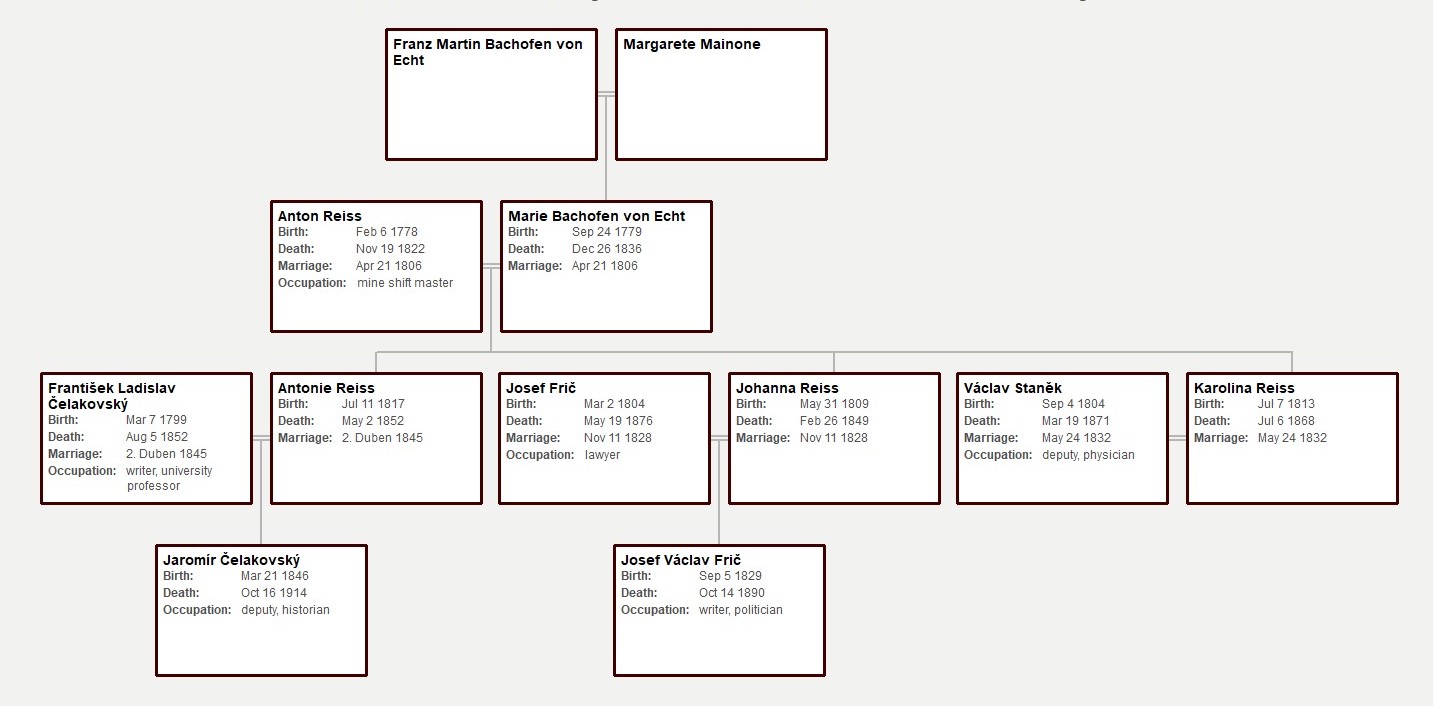

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

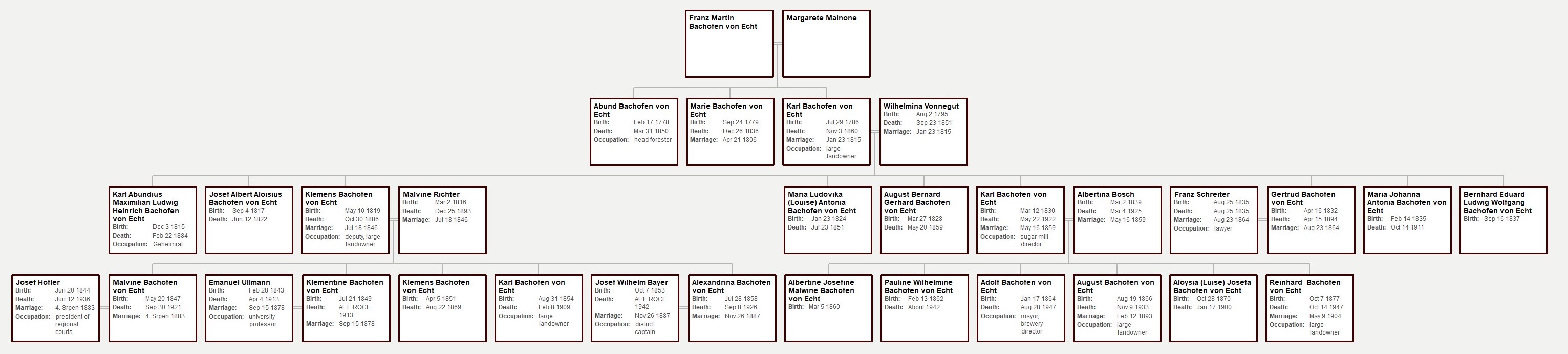

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

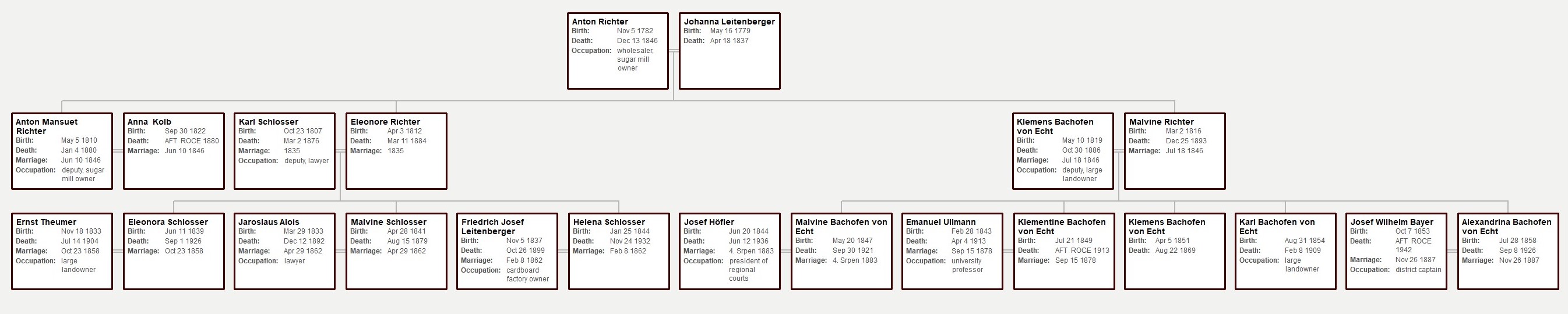

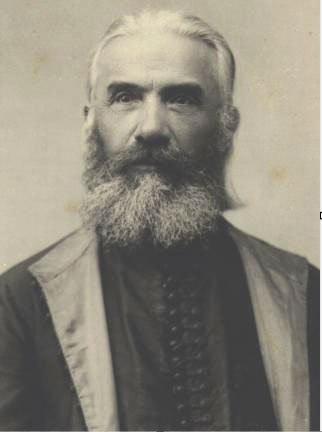

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

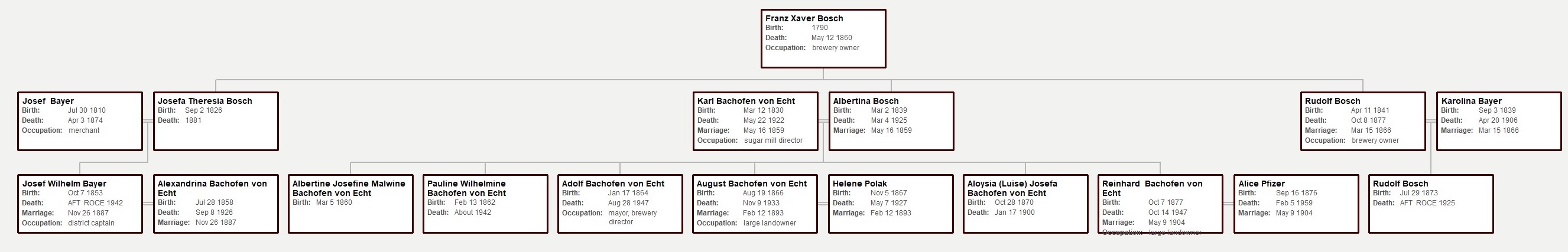

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

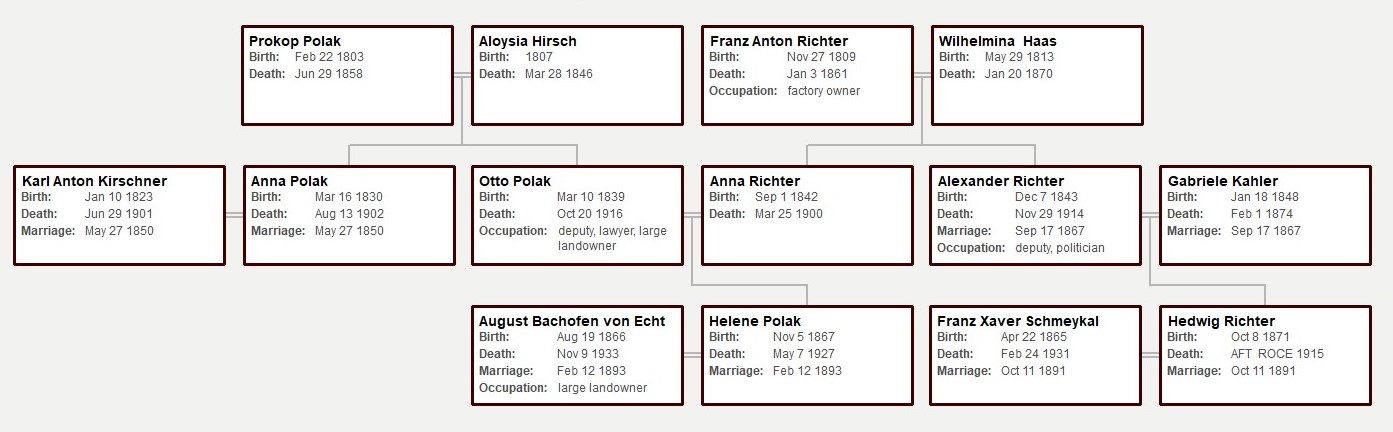

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

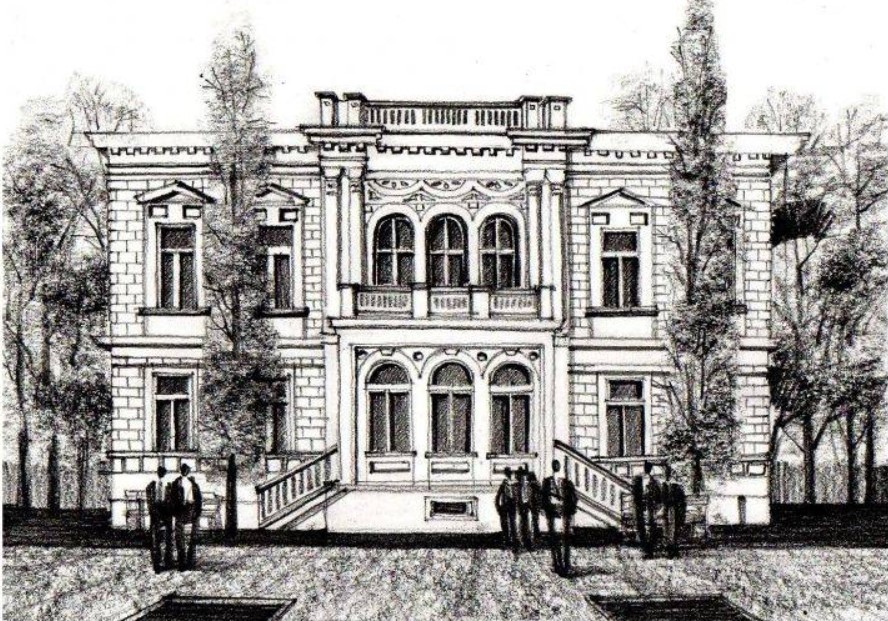

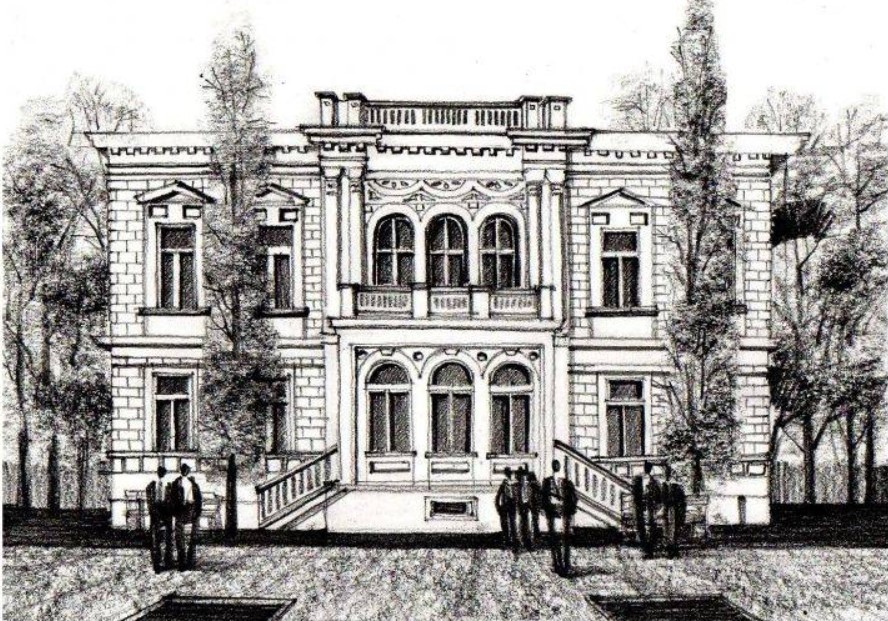

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

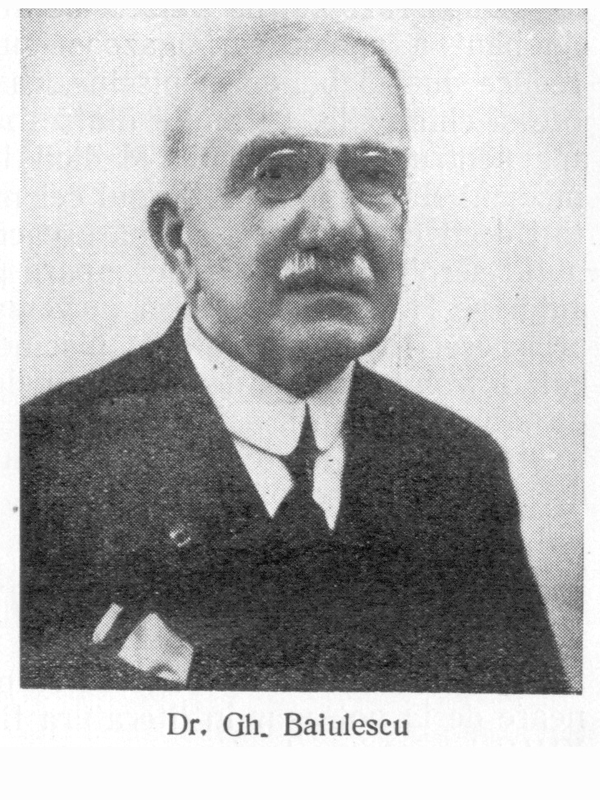

Gheorghe (George) Baiulescu was born in 1855, most likely in Brașov/ Kronstadt. He was the second child of priest Bartolomeu Baiul or Baiulescu (1831–1909) and Elena Gheorghiu (1834–1920), the daughter of a Romanian merchant from Wallachia. In 1855, Bartolomeu was the parish priest of the Orthodox Church of Zărnești, which is located 30 km away from Brașov, an important town in Transylvania with a significant German, Hungarian, and Romanian population. However, two years later, he became a priest at the Saint Nicholas Church in Brașov, where his son Gheorghe was baptized. The Baiulescu family had four children: Ioan (1852–1911), Gheorghe, Maria (1860–1941), and Romulus (1863–1941). The mother's origin from the south of the Carpathians contributed to the family's close ties with Romania, especially since Brașov was near the border between the Habsburg Empire and Romania. None of the three boys pursued a priestly career like their father. Ioan, a graduate of the Vienna University of Technology (1872–1877), settled in Romania and became a reputable railway and bridge construction specialist. He was a general inspector in the Ministry of Public Works and served as a professor at the School of Bridges and Roads. His brother Romulus also moved to Romania, where he became an engineer in the Ministry of Public Works and later headed railway management. The daughter, Maria Baiulescu, was a prominent figure in Transylvania, known for her extensive philanthropic activities, including assisting orphans and supporting women's emancipation.

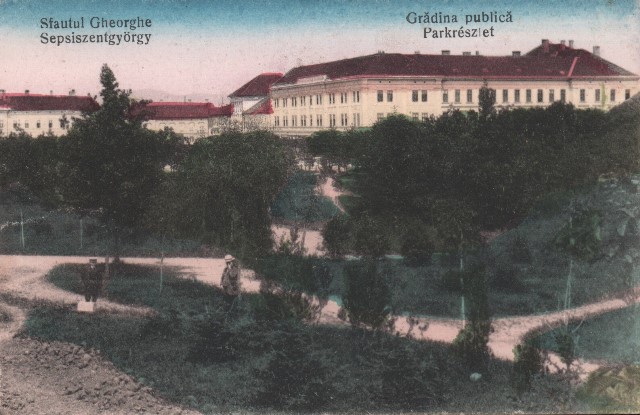

Gheorghe studied at the Romanian gymnasium and high school in Brașov, where he graduated first in his class in 1872. He chose to pursue his medical studies not in Bucharest or Budapest but in Vienna. There, he specialized in balneology under the guidance of Dr. Wilhelm Winternitz (1835–1917). In addition to his medical pursuits, Gheorghe was a gifted violinist and attended the Vienna Conservatory. Furthermore, he was a passionate classical musician and published articles on this subject. Upon returning to Transylvania in 1880, he was appointed as the physician for the Romanian schools in Brașov, and he also served there as a professor of hygiene. He played a crucial role in improving the education of Romanian pupils and enhancing the general health of the people of Brașov. He achieved this by establishing the Baths of the Administration of Romanian Schools, which included medical baths open to all, gaining him recognition in Transylvania and Romania. In 1893, he was appointed as the district physician. His reputation grew significantly, especially after his book Medical Hydrotherapy was published in Bucharest in 1904.

The Council Square in Brașov in the 1920s, România Ilustrată, April 1929

In 1885, he married Maria (?–1929), the daughter of Manole Diamandi, a wealthy merchant, president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, a philanthropist, and a politician closely aligned with the Romanian National Party of Transylvania. Manole Diamandi had a strong connection with Romania, not solely due to commercial interests but also because of his generous contributions supporting the War of Independence (1877–1878). It is worth noting that the Baiulescu and Diamandi families were acquainted well before this marriage. Maria, Gheorghe's wife, had a philanthropic role as well. However, it may be challenging to distinguish her activities in the press, as they could easily be confused with those of her sister-in-law, Maria B. Baiulescu.

Baiulescu House, a wedding gift from Manole Diamandi, https://www.metropola.ro/ro/ghid/brasov/descopera/turism/muzee/casa-baiulescu-/1637/

An advocate for the national rights of the Romanian minority in Hungary, in August 1916, G. Baiulescu unequivocally supported Romania's entry into World War I against Austria-Hungary. He had connections within the Romanian political elite, particularly with the Liberals, including engineer Ionel I.C. Brătianu (1864–1927), who served as Prime Minister from 1914 to 1918 (and held the office in later terms from 1922 to 1926 and 1927). Ionel Brătianu had been a colleague of Gheorghe's brothers at the Ministry of Public Works. In August 1916, under the Romanian military administration, Gheorghe Baiulescu was appointed as the mayor of Brașov. However, this appointment required him to follow the Romanian troops in retreat a month later. In May 1917, in Moldavia, along with Octavian Goga and Sever Bocu, he co-founded the National Committee of Romanians in Austro-Hungary and served as its president. His political activity aimed to support the Romanians in Transylvania and persuade them to abandon their allegiance to the Habsburg monarchy in favor of the Romanian state. In addition to his political involvement, he had a busy medical career, working in hospitals in Iași, Odessa, and Chișinău/Kishinev (Bessarabia). Due to his medical service, he was promoted to the rank of doctor Lieutenant Colonel.

The former mayor of Brașov became one of the prominent figures of the Transylvania emigrees during World War I and was a political partner of Brătianu. He served as the first prefect of Brașov County, appointed by the Transylvanian Ruling Council in January 1919. He held this position until December 1920, when he was promoted in Bucharest as a general administrative inspector of the Ministry of the Interior. This high-ranking public role was typically occupied by individuals who had demonstrated their organizational capabilities. They retained their office even after changes in the government. As a general administrative inspector, Baiulescu conducted inspections throughout the country, oversaw the prefectures, and advised the minister and the secretary-general of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. On certain occasions, as with Baiulescu, these high-ranking public officials were appointed as acting prefects for counties until a permanent prefect could be assigned, and this interim period could extend for several months. Consequently, Gheorghe Baiulescu served as the acting prefect of Brașov County on three separate occasions (December 1921 – January 1922, February 1923, and July 1923 – January 1924). His close ties to members of the National Liberal Party of the Old Kingdom predate 1916. Still, they became more pronounced after 1922, even though Baiulescu was a tenured prefect under various governments. In fact, in Brașov County, as well as in other Transylvanian counties after 1919, Baiulescu leveraged his influence to influence the appointment of prefects and other dignitaries, often to the benefit of his pre-war or refugee acquaintances.

Baiulescu's social and political involvement in the development of Brașov County was further complemented by his economic interests and various financial investments. He was a member of numerous boards of directors both before and after 1918. Several buildings in Brașov serve as reminders of his legacy: the Baiulescu House, gifted to Gheorghe and Maria by Manole Diamandi (on the present-day Eroilor Boulevard, no. 33) and later donated by the Baiulescu spouses to the city of Brașov, another house that would eventually become one of the headquarters of the local Communist Party (Nicolae Iorga Street, no. 2), and a villa constructed for his family in the 1920s (Nicolae Iorga Street, no. 26). Dr. Baiulescu also played a vital role as the founder and administrator of the Zărnești Cellulose Factory in the 1920s.

Maria and Gheorghe had two sons. Emil (1886–1967) pursued law studies, earning a doctorate in Law and becoming a judge in Brașov. Their second son, Aurel, was likely a law graduate. He served as a reserve cavalry captain. Tragically, his passion for gambling is believed to have led to his suicide via a morphine injection in a hotel room in Brașov in 1932. At the time of his suicide, his brother Emil held the position of president at the Brașov Court of Law.

Gheorghe Baiulescu passed away in 1935. He was interred, alongside other family members, in the cemetery of the Church of Saint Parascheva in Brasov, a church originally founded by his father.

The tomb of the Baiulescu family, the Church of Saint Parascheva cemetery in Brașov, Doctor Gheorghe Baiulescu Street, no. 16, https://scheiibrasovului.wordpress.com/tag/gheorghe-baiulescu/

Bibliography:

Stéphanie Danneberg, “Der Kronstädter Händler Diamandi Manole (1833–1899)”, in Historia Urbana, XXII, 2014, p. 341–353.

“De la înmormântarea inginerului Ioan Baiulescu”, in Gazeta Transilvaniei, LXXII, no. 7, 12 January 1911, p. 3.

Adrian-Horia Enescu, Gabriel-Ion Necula, Prefecți ai județului Brașov de odinioară, 1919-1939, Libris Editorial, Brasov, 2019.

L.N., “O sărbătorire românească la Brașov”, in Adevărul, XLIII, no. 14388, 20 November 1930, p. 2.

“Dr. Med. Gheorghe Baiulescu”, in Gazeta Transilvaniei, an XCIII, no. 120, 16 November, 1930, p. 1–2.

“Sinuciderea tânărului Baiulescu din Brașov”, in Universul, an XLIX, no. 303, 3 November 1932, p. 5.

Petcan, “Dramatica sinucidere a d-rului Baiulescu”, in Dimineața, XXVIII, no. 9288, 3 November 1932, p. 8.

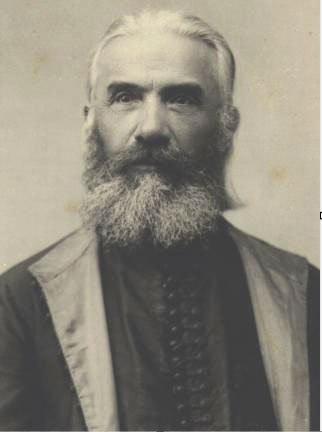

Leon Scridon sr. (1863–1942) was born on 27 November 1863 in the commune of Feldru, district of Năsăud, formerly (until 1851) part of the Austrian military frontier in Transylvania. His life and career illustrate both the social mobility within the political and social framework of the Dual Monarchy, in a family with a tradition in local administration, and the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the change of regime in 1919.

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

His grandfather on his father’s side, Simion Scridon, was a non–commissioned officer in the 17th Border Regiment and mayor of the commune. His father, Teodor Scridon (1834–1920) served eight years in the Habsburg army (1854–1862), rising to the rank of standard bearer. On his return he became mayor of the commune (1865), holding this office almost continuously, sometimes as communal cashier, for 34 years. In 1873 he was one of the founders of the “Feldru Loan and Safekeeping Association”, the first popular bank in the region. In 1863 he married Nastasia Pop, with whom he had five children (three boys and two girls).

Leon Scridon sr. (b. 1863), the eldest of the brothers, attended primary and secondary school in Năsăud, where he graduated from the local gymnasium in 1883. He went on to study law at the University of Cluj/Kolozsvár and obtained his bachelor degree in 1887 and his doctorate in state (administrative) sciences in 1889. During his studies he received a scholarship of 200 Gulden from the “Border Guards’ Funds” (the scholarship funds established from the assets of the former Border Regiment, which were only available to the Grenzer descendants).

In 1893 he married Maria Jarda (1875–1950), with whom he had three children: Ion (b. 1894), Elena (b. 1896) and Leon jr. (b. 1897). Between 1887 and 1922 Leon Scridon sr. pursued an administrative career, first as an official of Bistrița-Năsăud County in the Kingdom of Hungary, then as a county official and prefect in the Kingdom of Romania. In the Kingdom of Hungary, his career followed the linear course of most civil servants of the time. After two years as an administrative trainee (1887–1889), he was appointed notary of the orphanage see (1889–1890), then sheriff (Stuhlrichter/Szolgabíró) (1890–1891), county notary (1892–1906), and chief county notary (1906–1919). Among other things, he was well known locally at the time because his working day started at 5 A.M. In the Kingdom of Romania, opportunities for professional and social advancement increased. Between 1919 and 1921 he was appointed vice-prefect of Bistrița-Năsăud County, and on 29 December 1921 he was appointed prefect of Ciuc County, a position from which he retired a month later, in January 1922, when he reached the age limit required by law (35 years of service).

But this upward path was not without its challenges, especially in the early years after 1918. Immediately after the war, former pre-war Romanian officials retained their positions and many advanced in office (such as L. Scridon sr.), amid the resignation or refuge of Hungarian officials. However, they were not looked upon favourably by the nationalist radicals, who wanted to remove from administrative positions all those who had held office in the former political regime. Even if it did not go that far, the former officials were regarded with distrust. Not only political opponents, but also the armed forces were initially wary of the former officials. A report of the Romanian Volunteer Corps in December 1918 contains a list of public persons of Romanian origin in Transylvania who could be trusted to support the military operations of the Romanian Army in its advance westwards. This list does not include the name of Leon Scridon sr., but it does feature that of his son, Leon Scridon jr., at the time a law student.

Last but not least, the precarious economic conditions in the post-war years made it prone to abuse of office and speculation, with accusations also reaching senior officials. In mid-1919, rumours began to spread about an embezzlement supported by senior officials of Bistrita-Năsăud County, headed by the prefect and vice-prefect, who had allowed the sale, through third party traders of products from the warehouses of the former Habsburg army and had illegally issued export permits for such goods (export meaning that they had been sold outside Transylvania, in Bukovina). The investigation lasted almost half a year and ended with the acquittal of L. Scridon sr., who was reinstated in December 1919. A few months later, on 23 May 1920, amidst the tensions that had built up during the preparations for land reform, a group of 200 or 300 peasants forcibly removed the vice-prefect from office. As 28 of them were arrested, the next day more than 2000 peasants took to the streets in front of the prefect’s office.

The last step in his career, the one towards the position of prefect of Ciuc County, took place in December 1921, right at the end of the Averescu II government (13 March 1920 – 16 December 1921), of which the radical wing of the Romanian National Party, led by O. Goga, was part of. It is possible that his son Leon jr.’s relations with this political grouping contributed to the appointment, and the short period he held the office (just one month) indicates that it was a provisional, almost honorary, position before his retirement.

His relations with the public administration continued after retirement: in 1923 he was president of the county section of the Transylvanian Civil Servants Association, and from 1927 president of the county section of the Pensioners Association.

At the same time, he was also an official of civilian institutions, mostly related to the institutional legacy of the former Border Guards Regiment. He was a member of the General Assembly of the Forestry Funds (1889–1942), a member of the Administrative Commission of the same funds (1896–1923) and an assessor of the commission for the administration of the border guards’ forestry funds. He was also cashier and member of the church committee of the Greek-Catholic parish of Bistrița. Between 1912 and 1913 he took the necessary steps to establish the Romanian Women’s Association in Bistrița, drafted the statutes and was secretary of the Association between 1913 and 1919. His involvement in numerous other associations and charity initiatives was complemented by a similar degree of involvement in the local banking institutions. Between 1904 and 1942 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Aurora” bank in Năsăud, and from 1923 until his death in 1942 he was the manager of the Bistrița branch of the same bank. During 1901–1920 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Bistrițiana” bank (vice-president 1911–1915), and during 1926–1930 a member of the board of directors of “Regna”, a logging company operating in the forests of the border guards communes. He was also a member of the board of directors of the “Hebe” company, which managed the thermal baths in Sângeorz Băi. In short, he had a seat and a say in almost every (if not all) institution that mattered at county level, in all branches of public life, for more than forty years.

When Leon Scridon sr. died in Năsăud, in 1942, part of his family, one of the most respected and well-placed in the former military frontier, was in refuge in Romania after the takeover of Northern Transylvania to Hungary. His son Ion Scridon pursued a medical career. His daughter Elena was married to General Grigore Bălan (1896–1944), who died in 1944 in the battles for the liberation of Transylvania. Leon jr. studied law and at a young age became close to the political group led by Octavian Goga (1881–1938). He was a member of the Romanian Parliament (1937, on the lists of the National Christian Party), secretary of state, then secretary for the Someș land (Ținutul Someș) on behalf of the National Revival Front (1940) and general commissioner for Romanian refugees in Northern Transylvania (1940–1944). After the establishment of communism, he was sentenced twice: once in 1949 by the People’s Tribunal in Năsăud, and a second time in 1955 by the Bucharest Territorial Military Tribunal. He was pardoned and released from prison on 12 September 1955.

The four generations of the Scridon family that succeeded each other between the early 19th and the mid-20th centuries illustrate different patterns of social mobility, at different levels and in different chronological periods and political contexts: the role of tradition and administrative position in what might be called the “rural elite” (Simion and Teodor Scridon); the importance of education for the processes of social mobility taking place from the second half of the 19th century onwards (Leon Scridon sr.); the impact of changes in the political regime on members of the elite (upward in 1919 for Leon Scridon sr., then for his son Leon jr., and downward after 1948 for the latter).

Bibliography

Cornel Grad, Contribuția armatei române la preluarea puterii politico–administrative în Transilvania. Primele măsuri (noiembrie 1918–aprilie 1919), „Revista de Administrație Publică și Politici Sociale”, II, 2010, nr. 4 (5), p. 52–79 (55–56).

Vasile Ilovan, Aspecte ale mișcării revoluționare și democratice în județul Bistrița–Năsăud, „File de Istorie”, II, 1972, p. 167–182 (173–174).

Ironim Marţian, Onisim Filipoiu, Leon Scridon senior (1863–1942), „Buletinul Cercului Științific Plaiuri Năsăudene Bistrița”, IV, 1983, p. 36–59.

Adrian Onofreiu, La cumpăna veacurilor şi a vremurilor. Leon Scridon Sen. în apărarea averilor şi a Liceului Grăniceresc din Năsăud, „Arhiva Someșană”, seria III, 14, 2015, p. 67–85.

Teodor Tanco, Leon Scridon schiţase o istorie nescrisă nici pînă azi, in Teodor Tanco, Virtus Romana Rediviva, vol. 5, Bistrița, 1984, p. 282–286.

Iosif Uilăcan, Leon Scridon, in Adrian Onofreiu, Dan Lucian Vaida (eds.), Convergenţe etnoculturale. In Honorem Mircea Prahase, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2012, p. 291–308.

Press

Patria, I, 1919, 5, 7/20 February, p. 1.

România, III, 1940, 573–583, 8 January, p. 2.

Țara, IV, 1944, 910, June 18, p. 3.

Vasile Ladislau Pop (1819–1875) came from a priestly family of noble origin, living in Berind (Berend, Kolozs County). He was the second of the ten children of priest Ananie Pop and his wife, Anastasia. He attended elementary, secondary, and high school classes at the Roman Catholic (Piarist) High School in Cluj, where he was among the most diligent pupils of his generation. During this formative period he received a middle name that is the translation from Romanian into Hungarian of his first name (Vasile, which became Ladislau), thus resulting in his full name Vasile Ladislau Pop. After graduating from high school in 1835, he enrolled at the Faculty of Law in Cluj, which he graduated three years later. In 1838, thanks to his father’s intervention with Ioan Lemeni (1780–1861), the Greek Catholic Bishop of Blaj, he obtained a scholarship to study at the Theological Faculty of the University of Vienna, as a student of the Saint Barbara Seminary. Four years of theological studies followed in the capital of the Austrian Empire, where young Vasile Ladislau Pop completed his formative profile with theoretical notions and the German language, which were to be particularly useful in his later career. The Viennese studies facilitated his insertion into an extremely complex formative environment, which allowed access to readings and ideological trends that proved to be particularly stimulating for his political and cultural horizon. It was during this period that Vasile Ladislau Pop came to study the works of Transylvanian Romanian illuminists, such as Petru Maior (1756–1821), Gheorghe Șincai (1754–1816), and Samuil Micu (1745–1806), who historically and linguistically affirmed and legitimized the Roman origin of the Romanians as an indisputable argument for recognizing the Romanians as a political nation with equal rights alongside the other political nations in Transylvania.

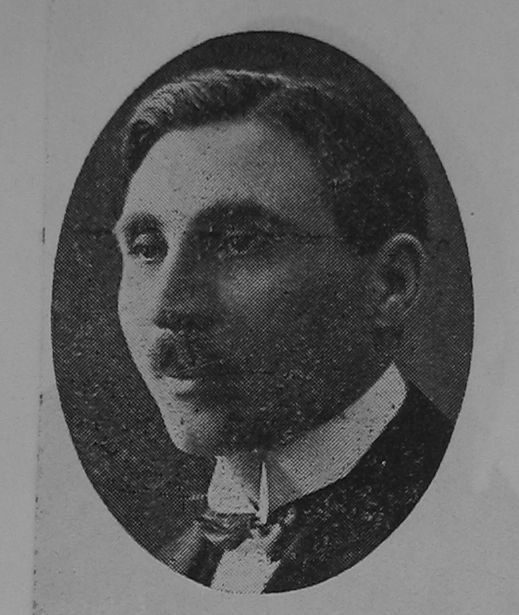

Image source: “Oameni de știință și cultură din Reghin și împrejurimi”, Album, 11, Petru Maior Municipal Library (Biblioteca Municipală Petru Maior), Reghin, http://www.bibliotecareghin.ro/index.php?Book=43.

After completing his studies in Vienna, Vasile Ladislau Pop returned to Transylvania, where he was appointed teacher of mathematics at the Theological Seminary in Blaj. Although he taught there for only three years, until 1845, his pupils and posterity remember him as the first teacher who taught mathematics in Romanian at the Seminary in Blaj. During the time he spent in Blaj, he also met a new generation of teachers, such as Ioan Rusu (1811–1843), Ioan Cristoceanu (1810–1844), and Demetriu Boieriu (1812–1871), with whom he became close. With some of them, he established a long-lasting friendships. We particularly refer to the teacher, historian, philosopher, and politician Simion Bărnuțiu (1808–1864), with whom he shared the same ideals and political-cultural projects aimed at the recognition of political rights for the Romanians in Transylvania.

His friendship with Bărnuțiu drew him into the Lemeni conflict in Blaj, during the period 1843–1846, between the new generation of teachers and the older one grouped around Bishop Ioan Lemeni, which led to his expulsion from Blaj.

The road to “Vienna, to the Emperor’s right hand”

For Vasile Ladislau Pop, the expulsion from Blaj (1845) was a major turning point in his professional career. Sent by his father to study theology to become a priest, but expelled by his bishop because of divergent opinions, Vasile L. Pop decided to abandon his clerical career for good to pursue a legal career. That was the moment in which he promised his father that he would only return home when he “arrived at the right hand of the Emperor”. Consequently, in the same year 1845, he enrolled in law studies at the Royal Board (Court of Appeal) in Târgu Mureș, which he graduated in 1848, obtaining a lawyer’s diploma. He began his career in Reghin, where he had met the young Elena Olteanu in 1846, and married her in the autumn of 1848. From the very beginning of his legal career, he benefited from the support of the Olteanu family and their relatives, which made it easier for young Vasile L. Pop to enter the intellectual circles of Transylvania. Vasile L. Pop’s in-laws, a family of merchants, enjoyed a good reputation in the area, and Elena’s maternal uncle, also a merchant, openly assumed his support for the two.

In 1849, Vasile L. Pop was appointed district commissioner in Reteag (Bistrița County), and shortly afterward, legal advisor at Bistrița Justice Court. It was the beginning of an ascending administrative-political career, which took him, in the next two decades, to the highest positions and dignities held by a Transylvanian Romanian until then. After working as a legal advisor in Bistrița (1852) and as a legal advisor at the Supreme Court in Sibiu (1854), he was promoted to a legal advisor at the Ministry of Justice in Vienna (1859). The peak of his career came in the years of the “liberal thaw” at the beginning of the seventh decade of the nineteenth century, when he was named vice-president of the Transylvanian Government and president of the Transylvanian Supreme Court. In 1863, he was appointed private councilor of the Emperor. He was only 45 years old at the time and had managed, thanks to the superior education he had benefited from and to the support of his parents-in-law’s family, to take up some of the highest state positions held by a Romanian up to that point. He also participated as a deputy in the proceedings of the Transylvanian Diet in Sibiu, in 1863 and 1864. In that capacity, he helped to draft laws meant to establish rights for the Romanians, which were going to be equal with those of the other nations inhabiting Transylvania.

With the signing of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Vasile L. Pop was designated vice-president of the Court of Cassation in Budapest, a position he held until the end of his life. Moreover, in recognition of his merits in the service of the Romanians of Transylvania, in 1868, he was elected chairman of the Astra Association (Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People). He died on February 17, 1875, in Budapest, and was buried in Reghin, in the Olteanu family crypt.

The case of Vasile L. Pop is a good example of the social mobility of an individual who, coming from a priestly family, left this socio-professional category and pursued a legal career, which propelled him to the top of the political pyramid of Transylvania in the years of Austrian neoliberalism. Pop’s marriage to Elena Olteanu, her family’s support, and the kinship networks created around this family contributed to his social ascent.

Bibliography:

Federațiunea, 11–12, MDCCCLXXV, 9/21 February 1875, 33.

Transilvania. Foia Asociațiunii transilvane pentru literatura și cultura poporului român, 5, VIII, 1 March 1875, 49–51.

Nicolae Comșa, Dascălii Blajului. Seria lor cronologică cu date bio-bibliografice (Blaj: Tipografia Seminarului, 1940).

Elie Dăian, Al doilea președinte al Asociațiunii: Vasile L. bar. Pop 1819–1875 (Sibiu: Editura “Asociațiunii”, 1925).

Destiny has taken Christian Baselli-Suessenberg far away from his homeland – he moved to Australia, where became a post officer.

His full name was Ferdinand Wilhelm Christian Baselli von Süssenberg and he was born, apparently the day before Christmas Eve of 1909, to Helena (*1884) and Julius (*1873). Christian´s father was a major in the Austro-Hungarian army and his uncle Karel held the office of district captain. We do not know much about his youth beside the fact that he grew up in the Czech capital and in 1920 moved with his parents to Enns in the newly created Austria.

A turning point in Christian's life came in 1957, when he became a naturalized Australian citizen with a permanent residence in a suburb of Sydney. In the same year, he trained as a post officer and two years later successfully passed his examinations and became a full-fledged mail officer. By 1962 he worked in the accounts department, responsible for tax stamp distribution. In the end, Sydney became Christian's new home and he died 30 years later at the ripe old age of 82.

Available sources do not tell us whether Christian started a family in Australia and whether his possible descendants might be living there today. Still, thanks to the digitalized materials which the National Library of Australia makes available free of charge the story of his life could be at least partially unveiled.

Destiny has taken Christian Baselli-Suessenberg far away from his homeland – he moved to Australia, where became a post officer.

His full name was Ferdinand Wilhelm Christian Baselli von Süssenberg and he was born, apparently the day before Christmas Eve of 1909, to Helena (*1884) and Julius (*1873). Christian´s father was a major in the Austro-Hungarian army and his uncle Karel held the office of district captain. We do not know much about his youth beside the fact that he grew up in the Czech capital and in 1920 moved with his parents to Enns in the newly created Austria.

A turning point in Christian's life came in 1957, when he became a naturalized Australian citizen with a permanent residence in a suburb of Sydney. In the same year, he trained as a post officer and two years later successfully passed his examinations and became a full-fledged mail officer. By 1962 he worked in the accounts department, responsible for tax stamp distribution. In the end, Sydney became Christian's new home and he died 30 years later at the ripe old age of 82.

Available sources do not tell us whether Christian started a family in Australia and whether his possible descendants might be living there today. Still, thanks to the digitalized materials which the National Library of Australia makes available free of charge the story of his life could be at least partially unveiled.

Traian Moșoiu (1868–1932), officer, deputy and senator

Traian Moșoiu was a Romanian career officer and politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Romania. Traian Moșoiu was born on 2 July 1868 in Tohanul Nou, a village in Brașov County, Transylvania, which at that time was part of Hungary. His father, Moise Moșoiu (1830–1905), was a wealthy and ambitious peasant. He gained prosperity primarily from sheep farming but also became involved in local politics, serving as the mayor of Tohanul Nou and as a county councillor in Brașov. Traian Moșoiu’s mother, Ana née Răduțoiu (1845–1896), also hailed from a prosperous peasant family in Tohanul Nou.

Traian Moșoiu had six siblings: Ioan (1862–1945), Aron (1866–1889), Aurelian (1872–1946), Maria (1878–??), Aneta (1881–1900), and Paulina (1886–??). All the Moșoiu children received a quality education and entered into advantageous marriages. The sons that survived to adulthood, Ioan, Traian, and Aurelian, pursued notable careers, including serving as members of Parliament. In 1897 Traian Moșoiu married teacher Maria Fortunescu, who came from a wealthy family in southern Romania. Her brother, lawyer Constantin Fortunescu, served multiple terms in the Romanian Parliament and held the position of prefect before the Great Union of 1918. Traian and Maria Moșoiu had two children: Tiberiu (1898–1953) and Mariana (1903–??).

Traian Moșoiu began his education in his native village and continued at the Romanian Gymnasium in Brasov. Subsequently, he attended military studies in Budapest at the Royal Hungarian Ludovica Defense Academy and in Vienna at the Theresian Military Academy, graduating in 1890. After graduation, he was assigned to a military unit in Sibiu. However, due to his nationalist views advocating for the rights of Romanians in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, he faced conflicts with his superiors and was even sentenced to prison. Realising that he had no future in the imperial army, he secured his release from prison on bail with his father’s help and clandestinely crossed the border into Romania. In 1893, he enlisted in the Romanian army as a second lieutenant, marking the start of a military career that would see him rise to the rank of major general.

Traian Moșoiu gained widespread fame and admiration during the First World War for his leadership and victories on the battlefield, commanding infantry divisions. Consequently, he was elevated to the rank of general and was decorated with numerous awards, the most distinguished being the French Legion of Honor, conferred upon him by general Henri Berthelot (1861–1931). In 1919, General Moșoiu spearheaded the Romanian army offensive in Transylvania, driving out the Hungarian Red Army from the north-west of the territory. His triumphant entry into Oradea (Bihor County), a pivotal city in the region, strengthened his status as a national hero. Under his leadership, the army advanced to Budapest, where General Moșoiu was appointed Commander of the Budapest Military Garrison and Military Governor of the Hungarian territories west of the Tisa River.

Traian Moșoiu during the First World War

At the end of 1919, Traian Moșoiu gave up his military career, entering the reserves, to embark on a prolific political career with the National Liberal Party. Several factors influenced this shift. On the one hand, general Moșoiu’s reputation was intrinsically linked to his wartime triumphs; the subsequent peace post-1919 curtailed avenues for similar military distinctions. On the other hand, in the evolving landscape of Romania, shaped by the seminal Great Union of 1918, the political arena presented a dynamic and promising domain for an individual of Moșoiu’s aspirations and prominence. The general had the advantage of a solid image capital, being popular not only among the elite but also among the masses, because in the public consciousness he was considered the hero who liberated Transylvania from Hungarian domination. Moșoiu was regarded as a man of simple origins who had risen in his career through his own efforts, who had not forgotten the social class to which he belonged by birth; apparently humble and approachable, he was revered as a leader who endured the tribulations of military campaigns alongside his troops. There were even several poems in circulation at the time praising the general’s heroism.

Traian Moșoiu and Queen Mary of Romania, wife of Ferdinand I of Romania

Traian Moșoiu and Queen Mary of Romania, wife of Ferdinand I of Romania

In his political tenure, Traian Moșoiu served as a member of parliament, both as a deputy and later as a senator, between 1922 and 1927. He held ministerial roles in Liberal governments led by Ion I. C. Brătianu (1864–1927), specifically as Minister of Communications (1922–1923) and Minister of Public Works (1923–1926). For almost a decade, he led the Bihor County organization of the National Liberal Party. However, his political journey was not without controversies. Accusations of nepotism frequently arose as his brothers and brothers-in-law ascended to prominent roles – deputies, senators, and prefects – and collaborated closely with Moșoiu on various legislative and economic initiatives. His son succeeded him as the leader of the Bihor Liberal county organization and also became a deputy in Parliament.

Traian Moșoiu passed away on 30 July 1932 in Bucharest. To this day, he remains one of the most revered figures instrumental in the formation of Greater Romania.

References:

Cristina Liana Pușcaș, General Traian Moșoiu, Muzeul Orașului Oradea, Oradea, 2019.

Marius Boromiz (ed.), Versuri uitate din Marele Război. Cântece și doine cătănești, Ed. Armanis, Sibiu, 2020.

Gheorghe Calcan, Generalul Traian Moșoiu în epocă și în posteritate, Editura Universității “Petrol–Gaze”, Ploiești, 2006.

Sandu Popii, “Cântecul lui Moșoiu”, Unirea poporului, no. 29, 1919, p. 1.

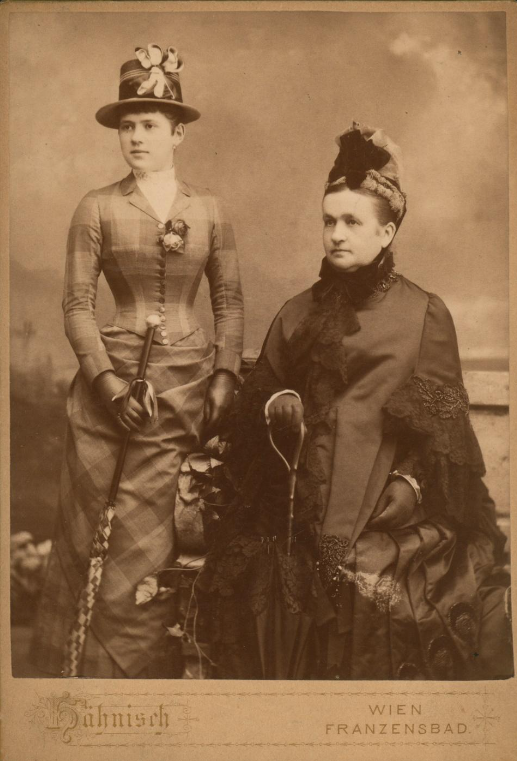

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

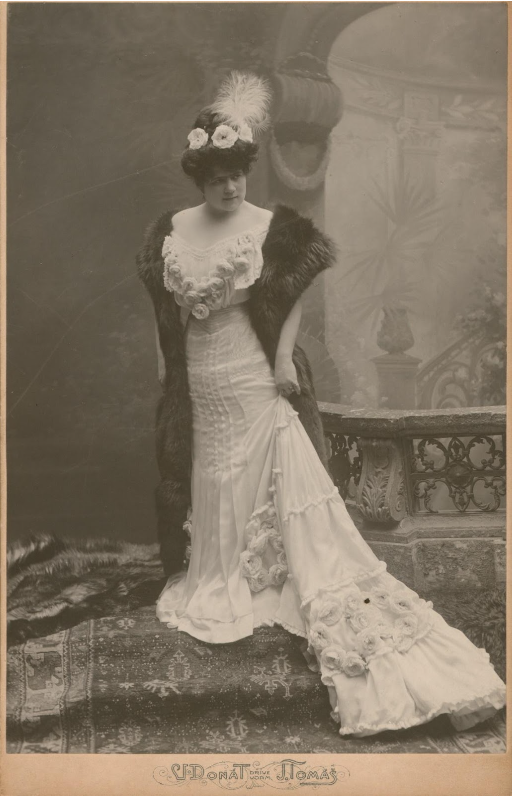

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.