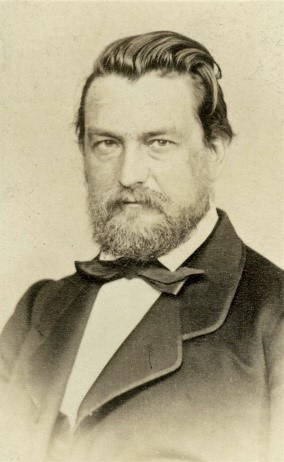

Solomon Haliță (1859–1926)

Image source: here.

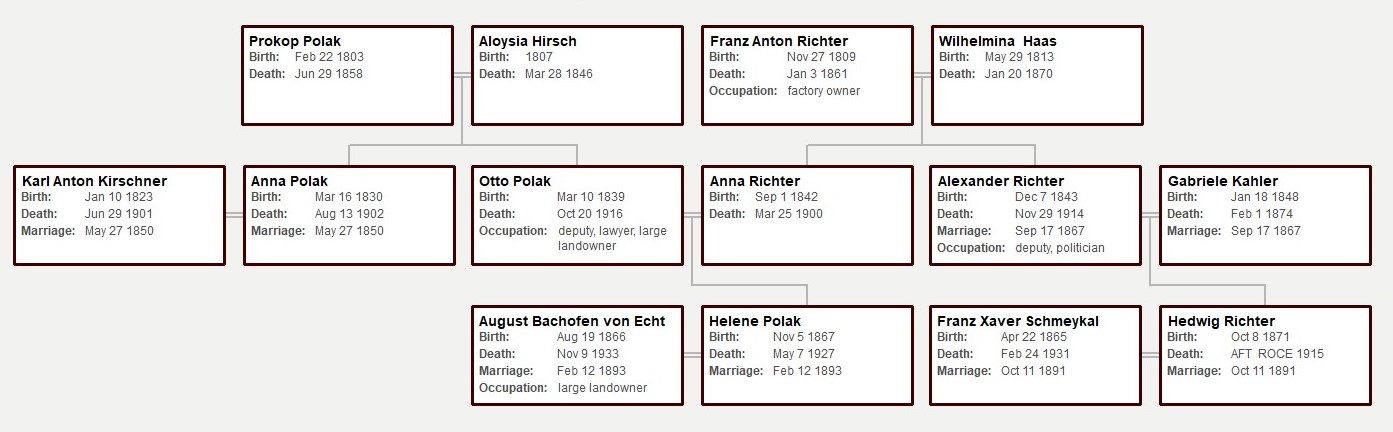

Maxim Haliță (1826–1893) came from a border guards family in Sângeorz Băi (Sângeorzul Român, Oláhszentgyörgy). He started as a village teacher during the 1840s, then served in the 17th (2nd Romanian) Border Guards Regiment during the Revolution of 1848–1849. After the military border system in the area was decommissioned he started a career in local administration: village notary (1851–1872), clerk to the district sheriff’s office (1873–1873), district sheriff (1873–1875), royal head-postman (1875–1889). In 1852 he married Ileana Ciocan (adopted by the family Isipoaie), and fathered four children: Elisabeta (1853–1915), Axente (1856–1865), Solomon (1859–1926) and Alexandru (1862–1933). (more, here)

His children were part of the first generation of young people who benefited from financial support for their studies, provided by the Border Guards’ Funds, an institution created following the decommission of the military border.

Elisabeta studied at the girls’ school in Năsăud (Naszód), then in Bistrița (Bistritz, Beszterce) and married Grigore Marica, a priest from Coșna – a nearby village. In 1879, her husband died after being accidentally wounded by her brother, Solomon Haliță (20 years old at the time), while returning from a hunting trip. As a consequence, Solomon vowed not to marry and have children, but to raise his three orphaned nephews, which he did, supporting them throughout their life. (more, here)

The youngest son, Alexander, studied Greek-Catholic Theology at Gherla (Szamosújvár) (1884–1888) and Letters at the Francis Joseph University in Cluj (Kolozsvár) (1888–1893). He was a teacher at the Highschool in Năsăud (1891–1911, 1920–1928), as well as parish priest of Năsăud and curate of Rodna (1911–1920). (more, here)

The best-known member of the family, however, was to become Solomon Haliță. He studied at the Highschool in Năsăud, where he distinguished himself and was also actively involved in the school’s literary societies (both the authorized and the secret ones). These societies were at the time a hotbed of Romanian nationalism and some of Haliță’s colleagues (Ioan Macavei (1859–1894), Corneliu Pop Păcurariu (1858–1904)) would later become journalists of the radical nationalist political newspaper “Tribuna”, and would spend time in prison for their articles. Haliță went on to study History and Philosophy, and Pedagogy at the University in Vienna, where he joined the Romanian Students’ Society “România Jună”, but also a smaller literary club called “Arborele” (The Tree), of only 17 members. The main objective of this club was to spread the cultural ideas from the Old Kingdom of Romania (in particular those of the “Junimea” Society) among the Romanians in Transylvania. (more, here) It is worth noting that more than half of its members later became public figures in the Romanian cultural and political milieu, and at least one of them (Septimiu Albini) linked up with Haliță’s former high school mates in the editorial office of “Tribuna”, and later also served time for press offences. (more, here)

After completing his studies in 1883, Haliță had difficulties finding a tenured teaching position back home, although, truth be told, he did not seem to have the patience to wait for an opening, as he emigrated very soon to Romania. In 1890 he renounced his Hungarian citizenship and became a citizen of the Kingdom of Romania. Between 1883 and 1919 he worked as a secondary school teacher in various towns, while at the same time building a bureaucratic career in the field of Public Education: 1889–1891, member of the General [i.e., National] Council of Instruction; 1896–1899, 1901–1904, 1907–1911, and 1914–1919 General Inspector of Schools. Much of his success was owed to the good relationship he developed with Spiru Haret, an important liberal reformer of education in early 20th century Romania. (more, here)

During the First World War, and especially during the retreat of the Romanian political authorities to Iași (1916–1918) Haliță developed even closer ties with representatives of the National Liberal Party, and in particular with Prime Minister, Ion I.C. Brătianu. Thus, he slowly shifted from being just an efficient and well-regarded bureaucrat in the field of Education to handling more sensitive political issues. In October 1918, he played the role of intercessor between the Romanian delegates from Transylvania and the Romanian government. He was then sent back to Transylvania to accompany Brătianu’s messages of political and military support and took part, in this capacity, at the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918. (more, here) This privileged position explains his temporary appointment as prefect of Iași in 1919. (more, here)

Between 1920 and 1922 Haliță returned to Transylvania as General (i.e., Regional) Inspector of Schools. In 1922 he was appointed prefect of his home county, Năsăud (Bistrița-Năsăud after 1925), an office he held until the fall of the Liberal government in April 1926. It was the peak of his career, something nobody would have envisioned forty years earlier, when he had left the same county as an émigré due to not finding a tenured teaching position. He died a few months later, on 1 December 1926.

Solomon Haliță’s career highlights the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the financial support for education in the former Austrian military border area, due to the transformation of regimental funds into educational and scholarship funds. It also illustrates the constant migration of Romanian university graduates from Austria-Hungary to Romania, which populated the civil service of the latter with highly qualified personnel, at all levels and in all branches of activity. Last but not least, it shows how the combination between professionalism and personal relationships (also built along professional lines), helped maintain a high bureaucratic position despite the changes in government, and how political support helped the leap from the ministerial bureaucracy to the administrative and political elite.

Literature

Septimiu Albini, Direcția nouă în Ardeal. Constatări și amintiri, in vol. Lui Ion Bianu amintire. Din partea foștilor și actualilor funcționari ai Academiei Române la împlinirea a șasezeci de ani, București, 1916. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban, Maxim Haliță – locuitor de frunte din Sângeorgiul Român, în „Arhiva Someșană”, XV, 2017. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban (ed.), Solomon Haliță, om al epocii sale, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2015. (here)

Ironim Marţian, Figuri de dascăli năsăudeni şi bistriţeni, Editura Napoca Star, Cluj–Napoca, 2002.

Adrian Onofreiu, Ana Maria Băndean, Prefecții județului Bistrița–Năsăud (1919–1950; 1990–2014). Ipostaze, imagini, mărturii, Bistrița, Charmides, 2014.

Grigore Pletosu, Moarte prin puşcă, în „Telegraful Român”, XXVII, 1879, nr. 91, 7 august, p. 359. (here)

Solomon Haliță (1859–1926)

Image source: here.

Maxim Haliță (1826–1893) came from a border guards family in Sângeorz Băi (Sângeorzul Român, Oláhszentgyörgy). He started as a village teacher during the 1840s, then served in the 17th (2nd Romanian) Border Guards Regiment during the Revolution of 1848–1849. After the military border system in the area was decommissioned he started a career in local administration: village notary (1851–1872), clerk to the district sheriff’s office (1873–1873), district sheriff (1873–1875), royal head-postman (1875–1889). In 1852 he married Ileana Ciocan (adopted by the family Isipoaie), and fathered four children: Elisabeta (1853–1915), Axente (1856–1865), Solomon (1859–1926) and Alexandru (1862–1933). (more, here)

His children were part of the first generation of young people who benefited from financial support for their studies, provided by the Border Guards’ Funds, an institution created following the decommission of the military border.

Elisabeta studied at the girls’ school in Năsăud (Naszód), then in Bistrița (Bistritz, Beszterce) and married Grigore Marica, a priest from Coșna – a nearby village. In 1879, her husband died after being accidentally wounded by her brother, Solomon Haliță (20 years old at the time), while returning from a hunting trip. As a consequence, Solomon vowed not to marry and have children, but to raise his three orphaned nephews, which he did, supporting them throughout their life. (more, here)

The youngest son, Alexander, studied Greek-Catholic Theology at Gherla (Szamosújvár) (1884–1888) and Letters at the Francis Joseph University in Cluj (Kolozsvár) (1888–1893). He was a teacher at the Highschool in Năsăud (1891–1911, 1920–1928), as well as parish priest of Năsăud and curate of Rodna (1911–1920). (more, here)

The best-known member of the family, however, was to become Solomon Haliță. He studied at the Highschool in Năsăud, where he distinguished himself and was also actively involved in the school’s literary societies (both the authorized and the secret ones). These societies were at the time a hotbed of Romanian nationalism and some of Haliță’s colleagues (Ioan Macavei (1859–1894), Corneliu Pop Păcurariu (1858–1904)) would later become journalists of the radical nationalist political newspaper “Tribuna”, and would spend time in prison for their articles. Haliță went on to study History and Philosophy, and Pedagogy at the University in Vienna, where he joined the Romanian Students’ Society “România Jună”, but also a smaller literary club called “Arborele” (The Tree), of only 17 members. The main objective of this club was to spread the cultural ideas from the Old Kingdom of Romania (in particular those of the “Junimea” Society) among the Romanians in Transylvania. (more, here) It is worth noting that more than half of its members later became public figures in the Romanian cultural and political milieu, and at least one of them (Septimiu Albini) linked up with Haliță’s former high school mates in the editorial office of “Tribuna”, and later also served time for press offences. (more, here)

After completing his studies in 1883, Haliță had difficulties finding a tenured teaching position back home, although, truth be told, he did not seem to have the patience to wait for an opening, as he emigrated very soon to Romania. In 1890 he renounced his Hungarian citizenship and became a citizen of the Kingdom of Romania. Between 1883 and 1919 he worked as a secondary school teacher in various towns, while at the same time building a bureaucratic career in the field of Public Education: 1889–1891, member of the General [i.e., National] Council of Instruction; 1896–1899, 1901–1904, 1907–1911, and 1914–1919 General Inspector of Schools. Much of his success was owed to the good relationship he developed with Spiru Haret, an important liberal reformer of education in early 20th century Romania. (more, here)

During the First World War, and especially during the retreat of the Romanian political authorities to Iași (1916–1918) Haliță developed even closer ties with representatives of the National Liberal Party, and in particular with Prime Minister, Ion I.C. Brătianu. Thus, he slowly shifted from being just an efficient and well-regarded bureaucrat in the field of Education to handling more sensitive political issues. In October 1918, he played the role of intercessor between the Romanian delegates from Transylvania and the Romanian government. He was then sent back to Transylvania to accompany Brătianu’s messages of political and military support and took part, in this capacity, at the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918. (more, here) This privileged position explains his temporary appointment as prefect of Iași in 1919. (more, here)

Between 1920 and 1922 Haliță returned to Transylvania as General (i.e., Regional) Inspector of Schools. In 1922 he was appointed prefect of his home county, Năsăud (Bistrița-Năsăud after 1925), an office he held until the fall of the Liberal government in April 1926. It was the peak of his career, something nobody would have envisioned forty years earlier, when he had left the same county as an émigré due to not finding a tenured teaching position. He died a few months later, on 1 December 1926.

Solomon Haliță’s career highlights the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the financial support for education in the former Austrian military border area, due to the transformation of regimental funds into educational and scholarship funds. It also illustrates the constant migration of Romanian university graduates from Austria-Hungary to Romania, which populated the civil service of the latter with highly qualified personnel, at all levels and in all branches of activity. Last but not least, it shows how the combination between professionalism and personal relationships (also built along professional lines), helped maintain a high bureaucratic position despite the changes in government, and how political support helped the leap from the ministerial bureaucracy to the administrative and political elite.

Literature

Septimiu Albini, Direcția nouă în Ardeal. Constatări și amintiri, in vol. Lui Ion Bianu amintire. Din partea foștilor și actualilor funcționari ai Academiei Române la împlinirea a șasezeci de ani, București, 1916. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban, Maxim Haliță – locuitor de frunte din Sângeorgiul Român, în „Arhiva Someșană”, XV, 2017. (here)

Alexandru Dărăban (ed.), Solomon Haliță, om al epocii sale, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2015. (here)

Ironim Marţian, Figuri de dascăli năsăudeni şi bistriţeni, Editura Napoca Star, Cluj–Napoca, 2002.

Adrian Onofreiu, Ana Maria Băndean, Prefecții județului Bistrița–Năsăud (1919–1950; 1990–2014). Ipostaze, imagini, mărturii, Bistrița, Charmides, 2014.

Grigore Pletosu, Moarte prin puşcă, în „Telegraful Român”, XXVII, 1879, nr. 91, 7 august, p. 359. (here)

Senior State Official and Deputy Ferdinand Conrad Johann Voith von Sterbez (1813–1882)

Ferdinand baron Voith von Sterbez

“[…] You have conquered the hearts of all the citizens […] by Your noble efforts and deeds. What wonder, therefore, that on this momentous day, when Your Eminence celebrates the precious feast of Your forty years of public service, the hearts of our fellow citizens, who have been privileged to witness Your beneficent work in the field of public administration […], rejoice.” These are the words of an official letter of congratulation addressed to Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez by the town council of Německý Brod (today Havlíčkův Brod / Deutschbrod) in 1875. Ferdinand Voith had been an exemplary civil servant, who managed to be popular among both his superiors and subordinates. He dedicated all his life to public service as a district captain, a member of parliament and a public figure.

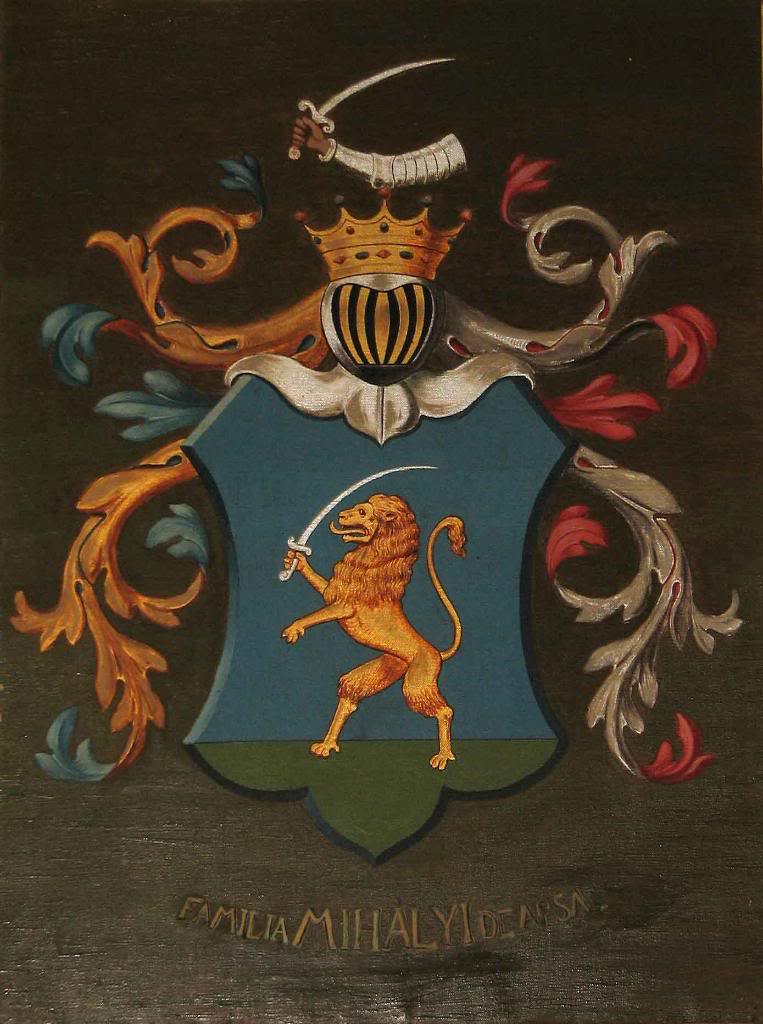

Coat of arms of the Voith von Sterbez family. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 55.

Ferdinand’s grandfather Johann von Voith (1746–1831) was an imperial officer and so was Ferdinand’s father Vincenz (1785–1845). However, after several years in the army Vincenz decided to leave and he became a hereditary postmaster. This was a prestigious position in the nineteenth century. Vincenz got this position because of his marriage to Theresia Kocy (1790–1838), whose father had held the post before him.

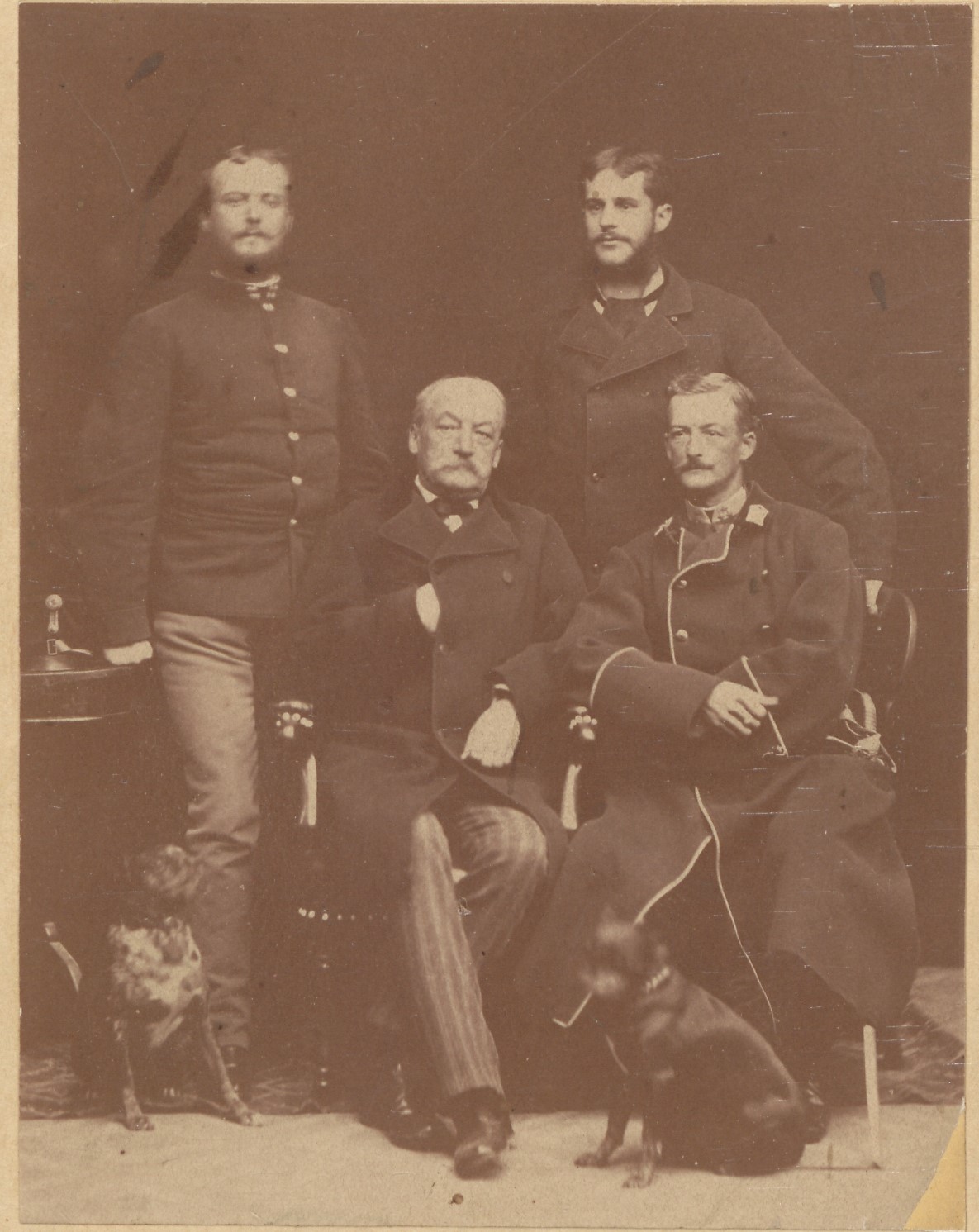

Family of Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 40.

Vincenz and Theresia were married for more than 30 years, but they had only one son – Ferdinand Conrad Johann, who was born on May 20, 1813, in Německý Brod. In this town Ferdinand also attended grammar school and probably had an opportunity to learn more about the Czech national revival. Karel Havlíček Borovský (1821–1856), a journalist and important personality for the Czech emancipation movement, went to this school as well, but at this point Ferdinand and Karel did not meet. After finishing secondary education, Ferdinand studied law in Prague, which was an essential prerequisite for his future in the state administration.

His first job was at the Land Governor’s Office in Prague as a trainee official. This stage of F. Voith’s career did not last very long, since he passed an exam and became a trainee official the following year. At this point of his career, he still did not receive any salary, but that did not prevent him from getting married and starting a family. In 1837 he married Maria Anna Theresia (1816–1885), daughter of Baron Johann Matzner von Herites (1769–1841).

Maria Voith von Sterbez born von Herites. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 39.

It was only in October 1849, when Ferdinand finally began receiving an adequate salary for his work. In 1868, after working in a few more Bohemian towns, he reached the position of a district captain at the District Captainship in Čáslav and kept this post until his death. The first years of marriage must have been difficult for both Ferdinand and his wife. They had ten children, who were born in four different towns. Four children died before they became adults. The financial situation of the family was not satisfactory either. Ferdinand had to borrow money repeatedly, but, fortunately, due to his status, there were always enough creditors willing to help him out.

Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez and his sons. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 42.

Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez served the Austrian state at the time when the authorities were supposed to oppress any kind of anti-government resistance. The difficulties of his position within the system may be best demonstrated in his relationship with Karel Havlíček Borovský, who was constantly critical of the Austrian government. For his public comments he was arrested in December 1851 and Ferdinand, as a representative of the local administration, was present during this arrest. Later on, Ferdinand’s daughters claimed that their father tried to warn Karel, but there is no proof for this. It is clear that Ferdinand helped Karel, when the journalist was in exile in Brixen, but Ferdinand never forgot that he was first and foremost a civil servant, who served the Austrian state.

When Ferdinand’s position in the state administration was stable, he entered another public sphere – politics. In 1861 he became a deputy in the Bohemian Diet for the curia of rural communities. Ferdinand was obviously popular among village mayors, who formed a significant part of the electorate. During his six years in the diet, he usually endorsed bills which limited the power of large estate owners and supported the rights of all nations to rule their own things within the monarchy. In the 1860s, the involvement of civil servants in politics was accepted and even welcomed by the authorities. The obvious conflict of interests did not represent a problem. This changed in the 1880s, when the government prohibited state officials from entering politics in order to secure their neutrality.

As mentioned before, Ferdinand and Maria had ten children together, but four of them did not survive their childhood. The oldest daughter Maria (1838–1900) got married twice. Her first husband was Philip von Behacker (1809–1884), a Court Secretary, and her second husband was Jan Němeček (1837–1908), a bank clerk. Her younger sisters Bertha (1844–1920) and Hermine (1851–1921) never married and spent their lives living together in Kolín. As they were not in a position to earn their own salary, they lived on their parents’ inheritance. The oldest son Vincenz (1842–1912) embarked on a military career and achieved the rank of major. The second oldest son Rudolf (1848–1905) join the army as well and became a captain. He married Anna Maria Tiegel von Lindenkron (1862–1929), the heiress of the estate of Osečany. The youngest son Ferdinand (1856–1885) started to study at Technical College Prague but died of tuberculosis at the age of 29.

Hermina Voith von Sterbez. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 44.

Berta Voith von Sterbez. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 44.

Hermina and Berta Voith von Sterbez. SOkA Kutná Hora, fonds Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez, box 3, call number 45.

Ferdinand Voith von Sterbez died on 10 February 1882 in Čáslav, a town, which became his destiny. His creditor Vojtěch Weidenhoffer (1826–1901) noted in his diary on this day: “This evening Mr Ferdinand Baron Voith von Sterbez, a Junior Governor’s Office Councillor and honorary burgher of this town, passed away. He was a meritorious and much respected and admired man. May God grant him a peaceful rest.” The funeral was a huge event attended by thousands of people, which was without any doubt a manifestation of F. Voith’s importance for the local community.

Although Ferdinand came from a noble family, his ancestors did not belong to old aristocracy and did not secure a stable income for him and his children. Ferdinand’s origin might have been useful at the beginning of his career, but later it was mostly his skills and diligence, which helped him to succeed. Unfortunately, this was not enough to provide sufficient inheritance for his children. Ferdinand felt sympathy for the Czech national revival, but he was never disloyal to his employer – the Austrian state.

Archival Sources

Státní okresní archiv Kutná Hora (State District Archives Kutná Hora, SDA Kutná Hora), fonds Voith von Sterbez Fedinand.

Bibliography

Karásek ze Lvovic, Jiří. O „muži, jenž zatýkal Havlíčka“. Z materiálu ke vzpomínkám Jiřího Karáska ze Lvovic [About “the Man who Arrested Havlíček”. From Materials about the Memories of Jiří Karásek ze Lvovic]. Literární rozhledy XIII, no. 9, June and July 1929: 61–62.

Kazbunda, Karel. Karel Havlíček Borovský. Svazek 1. 1821 – revoluční události 1848 [Karel Havlíček Borovský. Volume 1. 1821 – Revolutionary Events of 1848]. Praha: Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky, Odbor archivní správy a spisové služby, 2013.

Kazbunda, Karel. Karel Havlíček Borovský. Svazek 2. Ústavní oktroj 1849 – konfinování 1851 [Karel Havlíček Borovský. Volume 2. Constitution of 1849 – Expulsion 1851]. Praha: Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky, Odbor archivní správy a spisové služby, 2013.

Kazbunda, Karel. Karel Havlíček Borovský. Svazek 3. Brixen, Doma [Karel Havlíček Borovský. Volume 3. Brixen, Home]. Praha: Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky, Odbor archivní správy a spisové služby, 2013.

Klečacký, Martin. “Císařský úředník a politická strana” [An Imperial Official and a Political Party]. In Úředník sluhou mnoha pánů? Nacionalizace a politizace veřejné správy ve střední Evropě 1848–1948 [The official as the Servant of Many Masters? Nationalisation and Politisation of Public Administration in Central Europe 1848–1948]. Edited by Martin Klečacký. Praha: Centrum středoevropských studií, společné pracoviště CEVRO Institutu, z.ú. a Masarykova ústavu a Archivu AV ČR, v.v.i., 2018: 43–58.

Klečacký, Martin. Poslušný vládce okresu. Okresní hejtman a proměny státní moci v Čechách v letech 1868–1938 [Obedient Master of the District: District Captain and Changes in State Power in Bohemia in the Years 1868–1938]. Praha: Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, 2021.

Steinbauer, Jan. O předcích zemského a říšského mladočeského poslance JUDr. Eduarda Brzoráda. Děje rodů von Herites, von Krziwanek, Delorme a Brzorád. [online]. [cit. 26.11.2024]. Dostupné z www.opredcich.cz

Tomek, Václav Vladivoj. Paměti z mého žiwota. Díl II [Memories from My Personal Life. Part II]. Praha: W kommissi u Františka Řiwnáče, 1905.

Vaněčková, Jana. Voith von Sterbez Ferdinand. Osobní fond (1730) 1813–1882 (1944) [Voith von Sterbez Ferdinand. Personal Fonds (1730) 1813–1882 (1944)]. Inventory of the State District Archives Kutná Hora. Kutná Hora 2011.

Weidenhoffer, Vojtěch. Deník: 1861–1899 [Diary. 1861–1899]. Ed. Michal Kamp. Havlíčkův Brod: Muzeum Vysočiny, 2012.

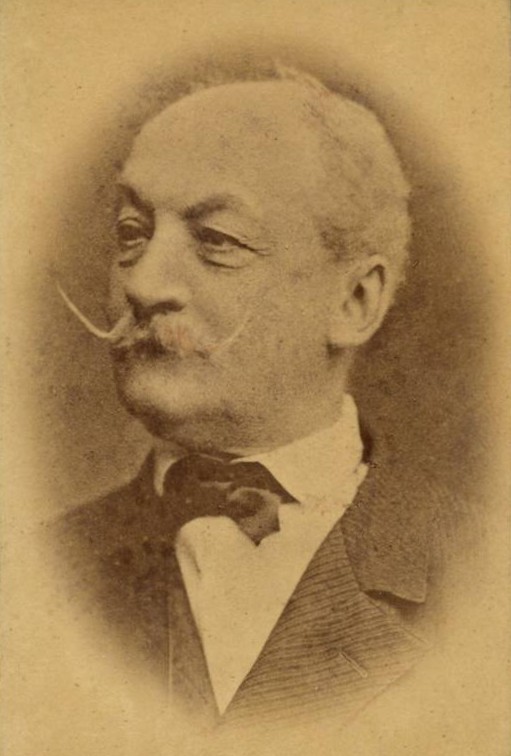

Petru Mihalyi of Apșa (1838–1914)

In the summer of 1887, the Greek Catholic Bishop of Lugoj (Hu. Lugos), Victor Mihalyi of Apșa (1841–1918), received a letter addressed to him by his brother, Petru, in which the latter notified his sibling that he had been successful in his bid for a seat in Parliament. Moreover, Petru shared his plans for his sons’ educations, designed to ensure that the Mihalyi of Apșa family would endure as one of most influential families in the Maramureș (hu. Máramaros) county:

“I passed through the elections with less emotion than 3 years before. […] During these 5 years [acting as MP], if the good Lord should keep me, I will live to see two of my sons completing their academic studies, my young lady grown up, being entirely content with this success. Little Petru is a very talented boy, we would like to raise him at home until he reaches 10, and then, if he were to succeed me, I’d send him to some military institute.”

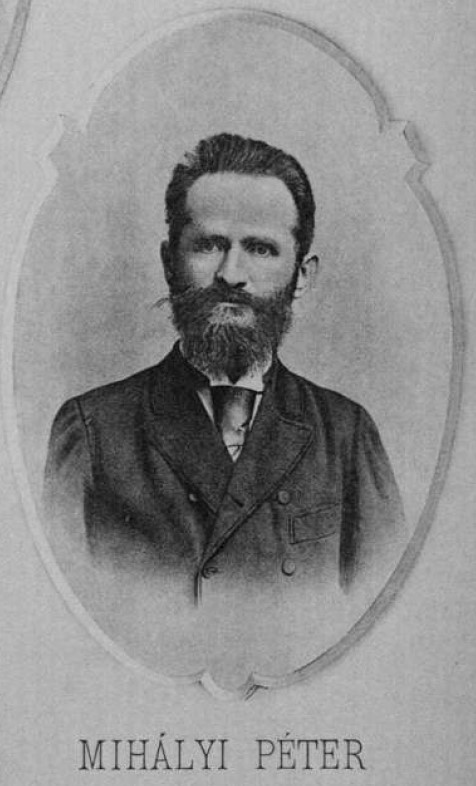

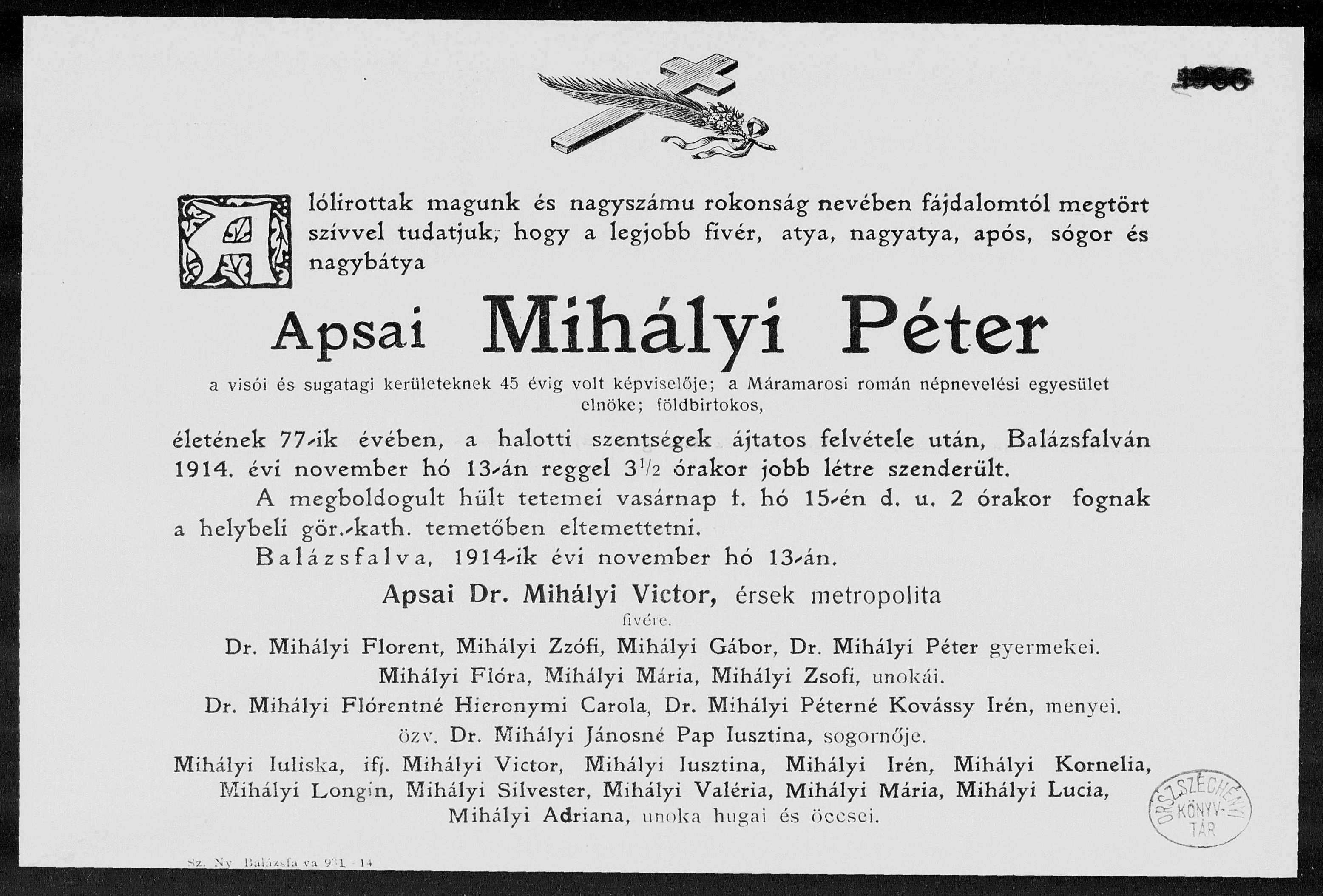

Petru Mihalyi of Apșa was the most longstanding Romanian Member of Parliament during the dualist period. According to his obituary, he was active in the Pest/Budapest Parliament over more than 40 years. He was born in 1838 in Ieud (hu. Jód), Maramureș (hu. Máramaros) county, in the house of his paternal grandfather, the Greek Catholic archpriest Ioan Mihalyi.

The Mihalyi family was one of the most influential families in the same county, having been granted a noble title in the 15th century by the Hungarian King Vladislav I (I. Ulászló). Petru’s father, Gavrilă Mihalyi (1807–1875), was also a MP and county commissioner of Maramureș. Petru’s mother, Iuliana, neé Man (1813–1881), was the sister of Iosif Man (1816–1876), who served as the Lord Lieutenant of the same county between 1865 and 1876. One of Petru’s brothers, who we noted above, was the clergyman Victor Mihalyi of Apșa, the Greek Catholic Bishop of Lugoj, who would go on to reach the highest ecclesiastical office in this Church and serve as Metropolitan of Alba Iulia and Făgăraș, residing in Blaj (Hu. Balázsfalva). A third brother, Ioan (1844–1914), while also occupying various offices in the administration of Maramureș county in the family tradition, would establish himself as a man of culture and become a corresponding member of the Romanian Academy. One of Petru’s cousins, Basil Jurca (?–1920), also followed in his footsteps and repeatedly served as a deputy in the Budapest Parliament.

Petru Mihalyi studied at the Oradea (Hu. Nagyvárad) and Košice (Hu. Kassa) gymnasiums, afterwards pursuing university studies in Vienna. It was in the imperial capital that he became knowledgeable in law and economics, two fields that would prove highly useful in his subsequent career in administration and politics. At the beginning of the 1860s, after completing his studies in law, he entered the civil service of the Maramureș county, where he served as high sheriff (Oberstuhlrichter/Főszolgabíró). He won his first mandate as parliamentary deputy in 1865, at the young age of 27, running in the constituency of Șugatag (hu. Sugatag), on the lists of the Deák Party (hu. Deák-párt). Thus, he began his vast parliamentary activity, which encompassed 12 parliamentary cycles between 1865 and 1910, interrupted only once between 1881 and 1884. During this lengthy time frame, he represented only two constituencies: that of Șugatag (1865-1869; 1887-1910) and Vișeu (Hu. Visó) (1869-1881; 1884-1887), both located in the Maramureș county.

Nevertheless, he did not prove himself to be as steadfast in his political options, vacillating between the opposition party and the government. He was initially part of the Deák Party, after which he joined the Liberal Party (Hu. Szabadelvű Párt), both of which were governing political parties. After 1879 he was past of the Moderate Opposition (Hu. Mérsékelt Ellenzék) and then the National Party (Hu. Nemzeti Párt), but at the 1896 elections he opted to re-enter the Liberal Party, of which he remained an adherent until its dissolution in 1906. During his final parliamentary cycle as acting deputy, he supported the policies of the Constitutional Party (Hu. Alkotmánypárt). He completed his political career in 1910, when he decided to renounce his candidature in favour of ‘little Petru’, who he mentioned in his letter to his brother. Petru Mihalyi Junior (1880–1951) won the 1910 elections as a representative of the electoral constituency of Șugatag, serving as a governmental deputy until the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy in 1918. He thus continued the political tradition of the Mihalyi family, as he was also active in the Parliament of Greater Romania during the interwar period. During this time, he also occupied the office of prefect of Maramureș.

As opposed to his forerunners, Petru Mihalyi also focused on extending his family’s sphere of influence beyond its regional boundaries, of the Maramureș county. Following in his family’s footsteps, he employed deft strategies as essential means of attaining this purpose. Petru Mihalyi was married to Luiza Simon (1842–1904), the daughter of Florent Simon (1803–1873), one of the most well-viewed lawyers in Budapest. His youngest son, Petru Junior, was married to Iréne Kovássy (1886–?), the daughter of the district court judge Géza Kovássy (1856–1910) from Rodna (hu. Óradna), Bistrița-Năsăud (hu. Beszterce-Naszód) county. It is doubtless that, from the perspective of marital ties, the greatest accomplishment was the marriage contracted by Florentin, his eldest son and a lawyer, who wedded Karola Hieronymi. Karola was the daughter of the Hungarian politician Károly Hieronymi (1836–1911), who had served as Minister of Internal Affairs during the government of Sándor Wekerle (1848–1821) and as Minister of Transports during the governments led by Károly Khuen-Héderváry (1849–1918) and István Tisza (1861–1918).

While the reach of his family’s influence as well as his excellent qualities as a politician were essential in obtaining such a high number of parliamentary mandates, an important role in his political success was, as Petru Mihalyi himself so aptly said, the fact that “I am very delicate when it comes to my political reputation, which I bear with great consequence [,] though with little material success, but with some dignity and moral gratitude.”

Bibliography :

- Fabro Henrik and Ujlaki József, eds., Sturm-féle Országgyűlési Almanach 1906–1911, [“Sturm” Parliamentary Almanac 1906–1911] (Budapest: Wodianer Ferenc és Fiai, 1906), p. 174-175

- Iudean Ovidiu-Emil, The Romanian Governmental Representatives in the Budapest Parliament (1881–1918) (Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2016), p. 165-169.

- Iuga de Săliște Vasile, Oameni de seamă ai Maramureșului. Dicționar 1700–2010, [Great people of Maramureș. Dictionary 1700–2010] (Cluj-Napoca: Societatea Culturală PRO Maramureș “Dragoș Vodă,” 2011), p. 727.

- Toth Adalbert, Parteien und Reichstagswahlen in Ungarn 1848–1892 (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1973), p. 286

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

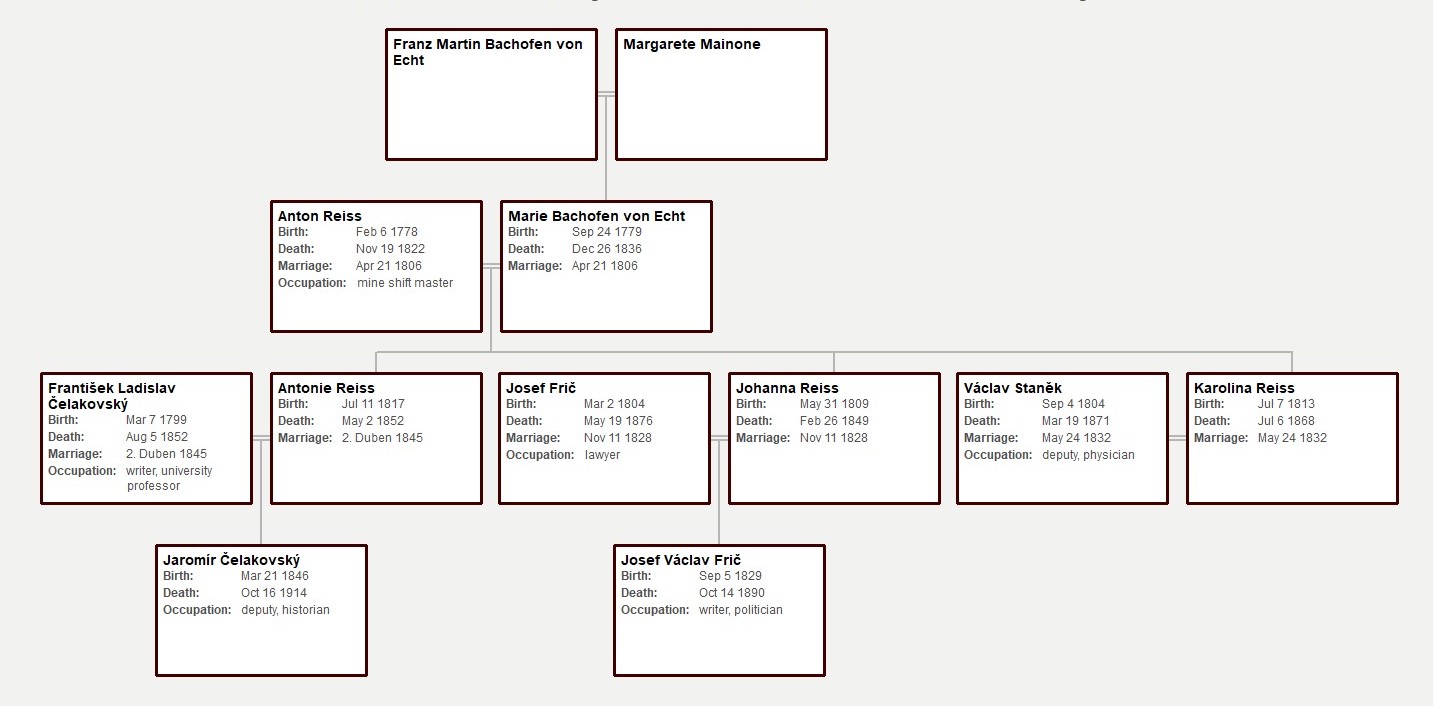

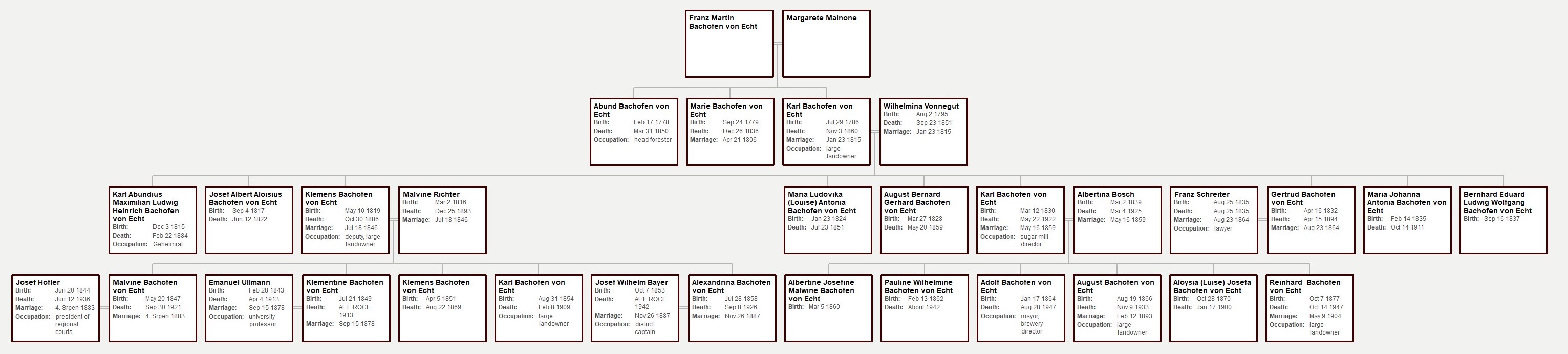

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

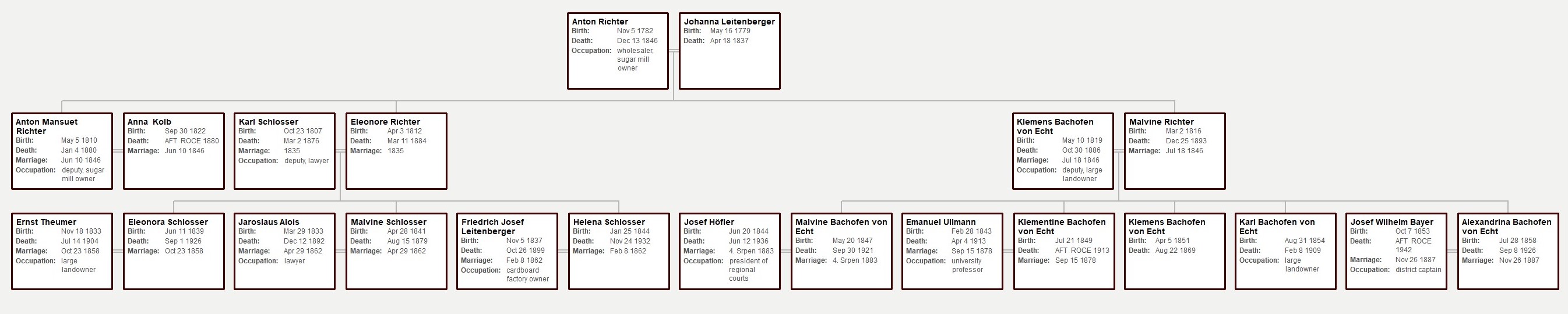

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

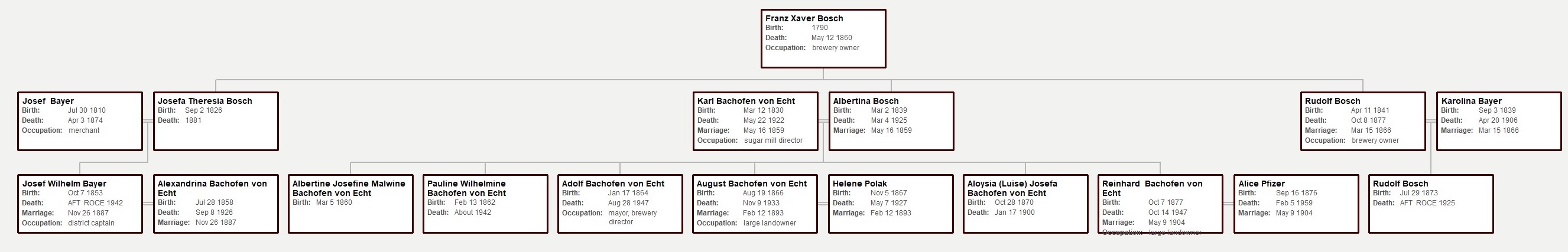

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4