Karl Andreas Fabritius (1826–1881), deputy, historian, pastor, teacher, journalist

The Saxon community in the 19th century Transylvania represents an interesting study case for how the changes operated in the entire Habsburg Monarchy manifested at a local level, especially for a group that was German, was a privileged minority in the region and started losing those privileges with the rise of nationalism. The Saxons were brought to Transylvania by various Hungarian kings during the 12th and 13th centuries when it was part of the Hungarian Kingdom. Despite being a demographic minority, they enjoyed longstanding privileges, including land grants, tax exemptions, and the monarch’s protection, even after Transylvania became autonomous under the Ottoman Empire and later the Habsburg Monarchy. However, the situation changed in the 19th century with the emergence of Austria-Hungary and the social transformations of the time. The privileges held by the Saxon community no longer aligned with the new political values of Hungary, which had direct control over Transylvania after 1867, so they were gradually abolished. In response, the Saxons, along with other ethnic groups in Transylvania, adopted various attitudes, influenced by the heterogeneity of political views within their elite. Examining the lives of key leaders within these political groups could provide valuable insight into the impact of these changes and their consequences for individuals. The case of Karl Fabritius offers intriguing insights in this regard. Although he faced massive backlash on the Saxon political scene for his views, he managed to maintain his political position and seat in the Hungarian Parliament, as well as propel some other aspects of his professional life, in the new political climate, which exemplifies the fate of the collaborationists in newly established regimes.

Karl Andreas Fabritius was born on the 28th of October or the 6th of November 1826 in Sighișoara/Schäßburg/Segesvár/, a locality in Transylvania of 3000 inhabitants. From his father’s side, he came from a family attested with the Latin name Fabritius since the 16th century, which gave numerous priests and civil servants. However, the branch of the family of Karl Fabritius was mainly active in crafts and industry, and “belongs to the more prestigious families of Sighișoara due to diligence and marriage connections.”[1] Both his grandfather and his father were craftsmen, the first a tailor, and the latter a bookbinder. His father, also called Andreas Karl Fabritius (1801–1879), married in 1825 Karoline Elisabeth, n. Schuller, daughter of Michael Schuller, a pastor of the Klosdorf/Miklóstelke/Cloașterf branch. Together they had four children: Ottilia (?–1846), who died as an unmarried mother; Sarolta (?–1879), who married a councilor from Sighișoara from Simonis family; Friedrich, who in 1883 was a district judge; and Karl Andreas (1826–1881).

Karl Fabritius studied at the local gymnasium under the guidance of Mihály Gottlieb Schuller (1802–1882), the director of the school, pastor and local personality. Schuller was the son of the pastor Michael Schuller from Cloașterf, thus being K. Fabritius’s uncle on the mother’s side. The relationship with him seemed to have improved Fabritius school performance. He also had as a teacher Georg Daniel Teutsch (1817–1893), a figure that was going to mark Fabritius’s life in major ways later. For higher education, Fabritius wished to pursue a career in law, but at his grandfather’s insistence and with his financial support, in 1847 Fabritius went abroad to study theology and history in Leipzig, where he was involved in the revolution of 1848. Due to financial problems, Fabritius applied later for support from the Austrian government, as well as from Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, a cultural Saxon association from Transylvania, of which he was a member. Still, this was not enough and in 1849 left for Vienna, where he met ministerial school councilor Johann Karl Schuller (1794–1865), who helped Fabritius in his historical pursuits. Fabritius soon moved to Bratislava as an editor for Pressburger Zeitung, and shortly after he received a position at Siebenbürger Bote, a newspaper in Sibiu/Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben, Transylvania. This was the reason for his return to his homeland in August 1850. However, Fabritius’s ideas were not well received by the owners of the newspaper, and he was fired after a month.

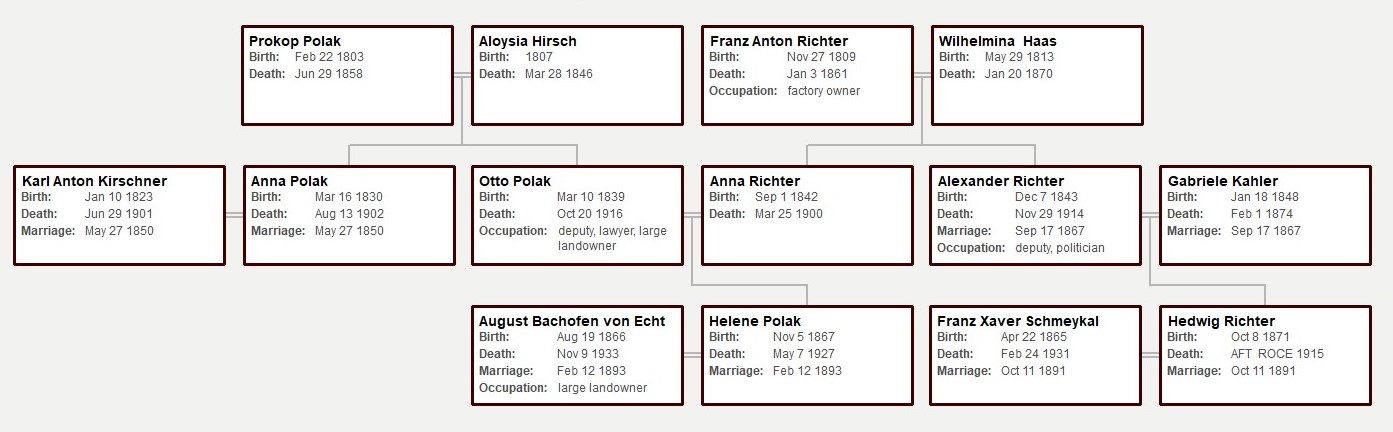

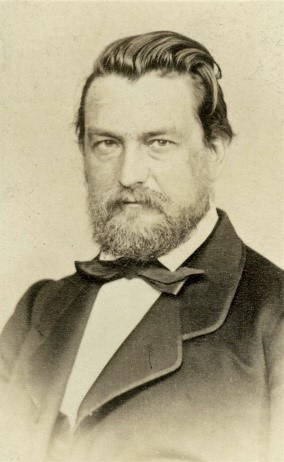

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

In October 1850 Fabritius obtained a position as a teacher at the gymnasium in Sighișoara, where G. D. Teutsch was a director at the time. Together with his former teachers M. Schuller and G. D. Teutsch, Fabritius also got more involved in the activities organized by Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, and through it, he started disseminating his historical research on which he worked since his studies. Due to some conflicts between the school’s director and the local consistory, Fabritius lost his teaching position in 1855, but soon after he was elected as a second town preacher in Sighișoara, a position much better paid than the one of a teacher. His luck changed afterwards. Fabritius applied for a pastor position in Merghindeal/Mergeln/Morgonda and Stejărișu/Probstdorf/Prépostfalva in 1857, then in Apold/Trappold in 1859. However, he did not succeed in any place, possibly because of his friendship with G. D. Teutsch. In 1861 Fabritius was named the first city preacher, but in reality, his salary was lower than before. He applied again for a pastor position in Brădeni/Henndorf/Hégen in 1865, but he was rejected.

K. Fabritius entered the political scene in 1867, at the time of the political compromise between Vienna and Pest that lead to the establishment of Austria-Hungary. He also became the “spiritual leader” of the “Young Saxons,” a political group of Transylvanian Saxons with liberal leanings and which considered collaborating with Pest, as well as with the other ethnic groups. This was in opposition with the political passivity adopted by the “Old Saxons”, the rival political group on the local scene. Between 1867 and 1881 Fabritius was elected five times as a deputy for Sighișoara on the lists of the governmental parties. He also became pastor in Apold in 1868. The sources do not mention any reason why K. Fabritius insisted on this village again, however, a branch of the Fabritius family had a few members that had previously been pastors or were connected to Apold. In 1872 Fabritius became a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Science, which further facilitated his historical research. In 1876, he received the opportunity to be appointed school inspector and even Lord-Lieutenant. Fabritius refused both positions, the reason being that he did not want any personal gain just for being a deputy.

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

However, Fabritius’s liberal and collaborationist political attitude with the Hungarian governmental party produced a rupture in his relationship with G. D. Teutsch, who after 1867 became the leader of the “Old Saxons.” Already at the beginning of his second mandate, Fabritius started receiving personal attacks from the opposition’s press. In 1872 Fabritius mentioned to his family his thoughts of quitting politics, because of the harassment he received, mentioning that he was continuing only to get access to the archives and libraries in Budapest. The attacks did not stop only at the political level. G. D. Teutsch became bishop of the Evangelical Church in Transylvania in 1867, and the president of Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde in 1869. Teutsch criticized Fabritius’s historical writings and prevented their publication by the Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde. Moreover, Teutsch questioned Fabritius on whether he could fulfill his duty in his parish, given his frequent trips to Budapest. The scandal gained proportions around 1875–1876 when Fabritius encountered difficulties in being reelected and received death threats. In 1879, Fabritius quit his position as pastor in Apold. Afterwards, he expressed he wanted to focus just on his historical research and less on politics, given the political losses for the Transylvanian Saxons in the past decade, although Fabritius still had a mandate. However, 1879 is also the last year he published something, his works afterward remaining in manuscript. An accident in the Budapest University Library in December 1880 probably also contributed to this. Fabritius was injured and this led to his death on 2nd February 1881.

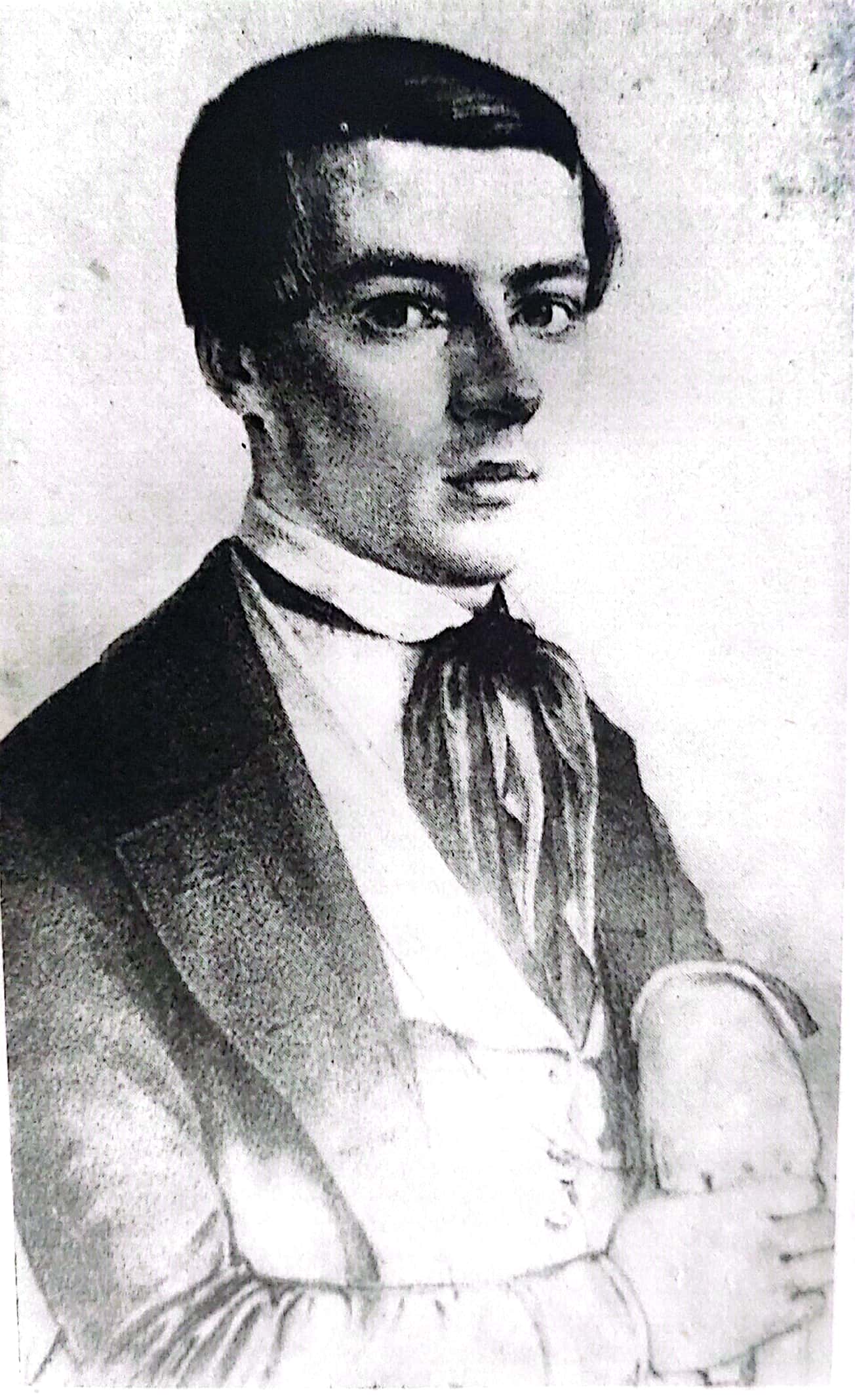

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

Very little information has been preserved about Karl Fabritius’s family, despite the long tradition of his family, as well as the number of children he had. Fabritius married in 1852 Friderice, n. Roth (1834–?), the daughter of Fridrich Roth, k. k. district judge in Cristuru Secuiesc/Szeklerkreuz/Székelykeresztúr, and of Amalia, n. Hirling. Karl Fabritius and Friderice had ten children together, of which only six survived to adulthood. Unfortunately, only five of their children could be identified in the parish registers, as not all of them were preserved. However, the ones still existent offer interesting glimpses in Fabritius’s family life. Ludvig Franz (1862–1863), Victorine (1864–1864), and Andreas Oskar (1868–1871) died in early infancy, while two other children survived well into their old age: Guido Robert (1865–1949), and Erich Bernhard (1872–1955). Details in the witnesses’ column for both Karl’s and Friedrice’s wedding, as well as for some of their children’s baptism seem to reveal another family connection. The name of Franz Simonis (1820–1884), another Saxon deputy from Transylvania, appears regularly, alongside that of Adolph Hirling. This makes sense as his sister was married in Simonis’s family, but also that Karl Fabritius might have had a relatively close connection to his mother-in-law’s family, related to that of Simonis through Franz Simonis’s marriage with Caroline Juliane, n. Hirling, in 1849. Also, it cannot be overlooked that one of Fabritius’s brothers, Friedrich, became a district judge, as Fabritius’s father-in-law, although his brother’s location is unknown.

More information about Guido Robert, one of Karl Fabritius’s sons, is revealed in one of his grandchildren’s biographies, namely of Guido Fabritius (1907–after 1989). Guido Robert left his hometown and moved to Sibiu, where he became the owner of the old Bären pharmacy. He married Melitta, n. Gunesch, daughter of pastor Gustav Hugo Gunesch, and together, they had seven children. Guido Fabritius was their only son and followed his father’s footsteps. He studied pharmacy in Cluj-Napoca/Klausenburg/Kolozsvár in 1932, then at the University of Berlin. He returned and worked at his father’s pharmacy, then took it over in his own name in 1936. He also co-founded the Deutschen Apothekerverband von Rumänien. During the war, he was part of the Wehrmacht (the Nazi unified armies). After the war, he lived in different cities in Western Germany, where he worked as a pharmacist, while he researched the Transylvanian pharmaceutical history, as well as his own family history, thus having a similar predilection for history as his grandfather. Regarding his familial life, Guido Robert married twice: in 1938 with Anne Schaffarczik, a secondary school teacher, with whom he had a daughter that died in early adulthood, and in 1952 with Luise Bleckmann-Körner, with whom he had a daughter and a son.

Selected bibliography:

Daubner, Hans D. “130 Jahre seit dem Tod von Carl Fabritius – eine Schäßurger Personlichkeit,” Schäßurger Nachrichten, no. 35 (June 2011): 24–25.

Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

Kozma, Ferenc. Emlékebeszed Fabritius Károly Levelező Tag Fölött, Budapest: M. T. Akadémia Könyvkaido-Hivatala, 1883.

Kwan, Jonathan. “Transylvanian Saxon Politics and Imperial Germany, 1871–1876,” The Historical Journal 61, no. 4 (2018): 991–1015.

Kwan, Jonathan. “Transylvanian Saxon Politics, Hungarian State Building and the Case of the Allgemeiner Deutscher Schulverein (1881–82),” The English Historical Review 127, no. 526 (2012): 592–624.

[1] Ferenc Kozma, Emlékebeszed Fabritius Károly Levelező Tag Fölött, (Budapest: M. T. Akadémia Könyvkaido-Hivatala, 1883), 4.

Wolfgang Achtner moved to New York where he settled and started a family.

Wolfgang Achtner was born on 19 December 1901 in Karlovy Vary. His father Karel Viktor (1863–1927) was a professor at a local grammar school and the son of a land school inspector Michael Achtner (1832–1877). Wolfgang's mother Olga (*1875) also descended from a well-situated family – her father Josef Fillén (1839–1889) owned a factory in the Karlín neighbourhood of Prague.

Early in 1926 Wolfgang set out on a journey across the ocean which originally was supposed to last only six months, but in the end lasted much longer. His ship set sail from Bremen on 27 February and after a 13-day voyage dropped anchor in New York. By that time, Wolfgang had already been an engineer.

It is not entirely clear whether he spent the whole of the next 22 years in the United States. What we may claim with certainty is that sometime during 1948 he married the twenty-four-year old Marion Hollister (*1924) from Massachusetts.

Even after many years, Wolfgang did not lose contact with Europe and in 1954, with his wife and a young son Wolfgang Michael (*1951), crossed the ocean again.

He did spend the rest of his life in America, however, and based on records from social security, this is also where he died in 1991. In Wolfgang's case, there is a chance that his descendants could still be living somewhere in New York.

What originally brought Wolfgang to the United States remains a mystery. It is not clear whether he really planned to stay for only six months, as he stated in official documents upon his arrival. Permanent migration often „happened“, without being planned in advance. Moreover, if the migrant married and started a family in his new home, the probability that he would return to his country of origin was even lower.

On 14 June 1810, in the Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Jihlava (Iglau), a local chaplain baptised the second-born son of the town lawyer Karl Friedl (1762–1846) and his wife Vincencie. The child was named Karl Anton.

J. W. Zwettler: Jihlava from the south. Lithography around 1850, call no. Ji-25/A/2142, from the collection of the Museum of Vysočina Jihlava

Karl Anton grew up with his three brothers and three sisters. His siblings’ education and their professions were determined by their father’s career. The elder brother Emanuel (1808–1866) started as a magistrate auscultant (an assistant judicial official or trainee judge who practiced in order to pass the judiciary exam and become an independent judge). Subsequently, he worked for many years as a municipal syndicus (a certified official “with a legal education in charge of judicial administration at the lowest level of justice administration”[1]) in Velké Meziříčí (Groß Meseritsch) and Moravská Třebová (Mährisch Trübau). He concluded his career with the title of councillor of the provincial court in Krnov (Jägerndorf) and Brno (Brünn). His youngest brother Johann (1819–1899) became a district commissioner in Šumperk (Mährisch Schönberg) and Brno (Brünn), later worked in Vienna, was secretary of the Provincial Commission for the Release of Subjects (established in 1849 after subjection was abolished in order to redeem subjects or settle other obligations to landlords[2]), and completed his career at the Czech Governorate in Prague as a governor’s councillor and later vice-president of the governorate.

Like his father and brothers, Karl Anton, too, received an adequate education and found a career in public administration. He became an official of the District (Indirect Taxation) Cameral Administration in Jihlava. The district cameral administrations established in 1833 were responsible for indirect taxes, customs duties and other charges (as well as for criminal proceedings in the area of indirect taxation). The district administrations were subject to the Cameral Indirect Taxation Administration in Prague or Brno.[3]

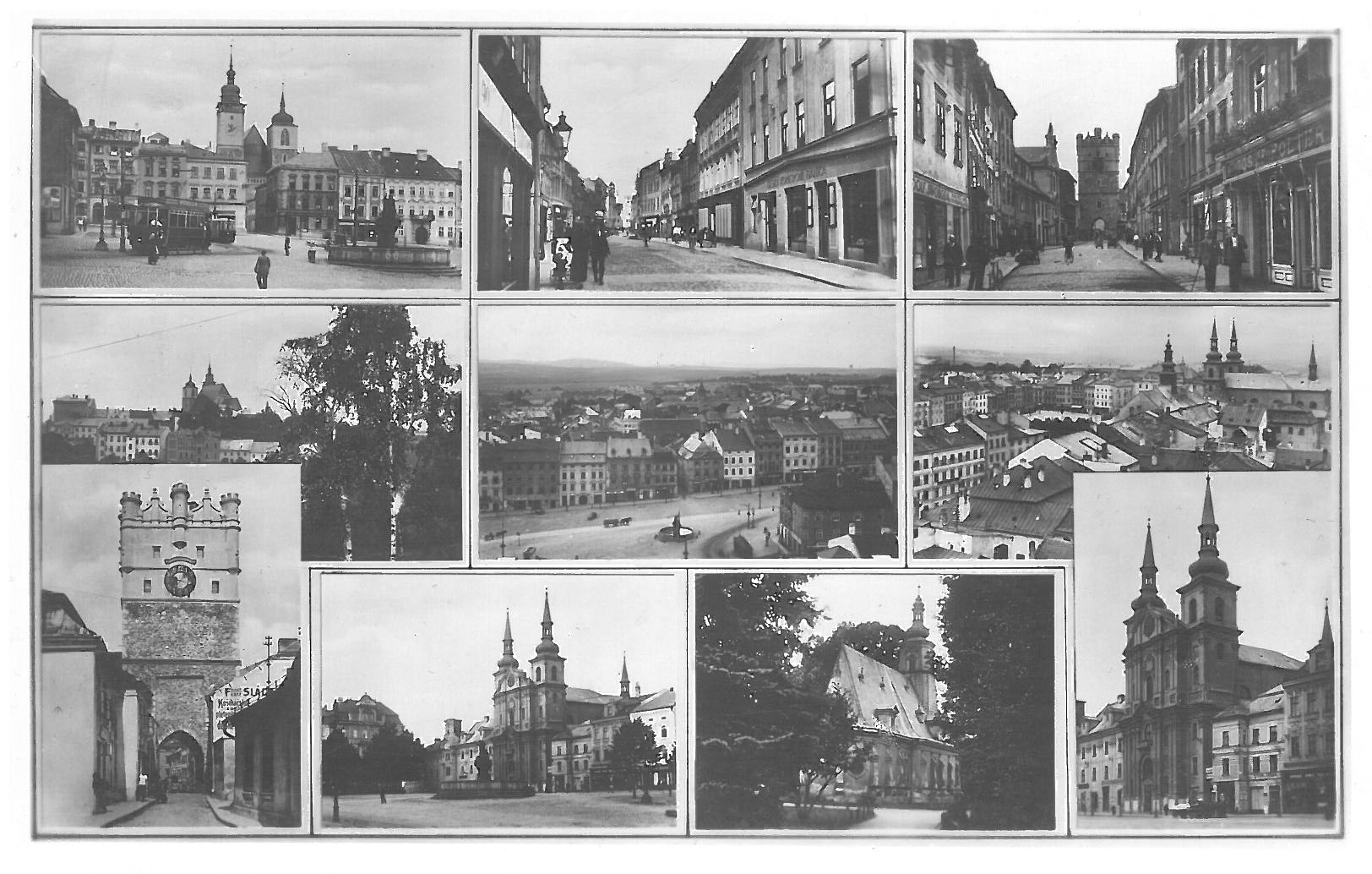

Postcard from Jihlava, not dated. Museum of Brno Region - Museum in Šlapanice, collection of the Museum in Šlapanice, historical collection, call no. H3562/145.

After successfully starting his career as a civil servant, what remained for Karl Anton to do was start a family. Unfortunately, he was not lucky in his private life. In November 1838, in St. Peter and Paul’s Cathedral in Brno, at the age of 28 he married Viktoria Franziska Eva (1808–1847), daughter of Karl Rüdt (1757–1841), the secretary of the Brno apellate court (court of appeal for towns). The young couple settled in Jihlava and three years after their wedding they were looking forward to the birth of their first child. However, shortly before Christmas, on 16 December, their daughter was stillborn. A few months later, Viktoria became pregnant again and the due date fell during Advent. Unfortunately, this time too, on 23 December 1842, another daughter was stillborn. The parents lived through yet another tragedy since not even Viktoria’s third pregnancy ended happily. In late October 1844 she gave birth to a stillborn boy. A year later, on 29 December 1845, a healthy daughter was finally born, named Sophie Karolina Vincencia (*1845) (Sophie Karolina after Karl’s younger sister, who died when she was only 10 years old). The family idyll, however, did not last long. In 1847, Victoria became pregnant again, but this time she did not survive the pregnancy-related complications. The widowed Karl Anton was left alone with a young daughter. Apparently, his mother Vincencie (*1780) helped him take care of little Sophie in Jihlava. Shortly after her third birthday, Sophie was orphaned. Karl Anton died of cerebral palsy (Gehirnlähmung) in January 1849.[1]

Edv. Harold: Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul in Brno. Magazine Světozor, year 1874, no. 28, p. 328

The fates of the sons of Karl Friedl Sr., with a focus on the family life of Karl Anton, reflect two contemporary phenomena: the difficult life of civil servants, who as a rule had to move for work; and the ubiquitous death. The sons of Karl Friedl Sr. followed in their father’s footsteps and found employment in the civil service. The brothers Emanuel and Johann slowly climbed up the secure career ladder, but could not avoid the obligatory transfer between various offices, i.e. moving from one place to another. It is true, however, that the transfers were not very frequent, and at the same time their career advancement was rather significant, which is a testimony to their abilities as well as to the confidence of their superiors. Karl Anton was a bit of an exception, having lived his entire life in Jihlava. However, had he been able to continue his career, it is almost certain that he would soon have been transferred to another city.

The life story of Karl Anton Friedl reflects the grim reality of his time: death was a significant part of everyday life. During the 19th century, conditions for children and expectant mothers slowly began to change, yet infant mortality was still relatively high at the beginning of the 20th century.

Literature:

HLEDÍKOVÁ, Zdeňka, Jan JANÁK a Jan DOBEŠ. Dějiny správy v českých zemích: od počátků státu po současnost. Praha: Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, 2005, p. 156, 278.

MALÍŘ, Jiří. Člověk na Moravě ve druhé polovině 18. století. Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury, 2008, p. 48 and following.

[1] Malíř, p. 48 ad.

[2] Hledíková, p. 278.

[3] Hledíková, p. 156.

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

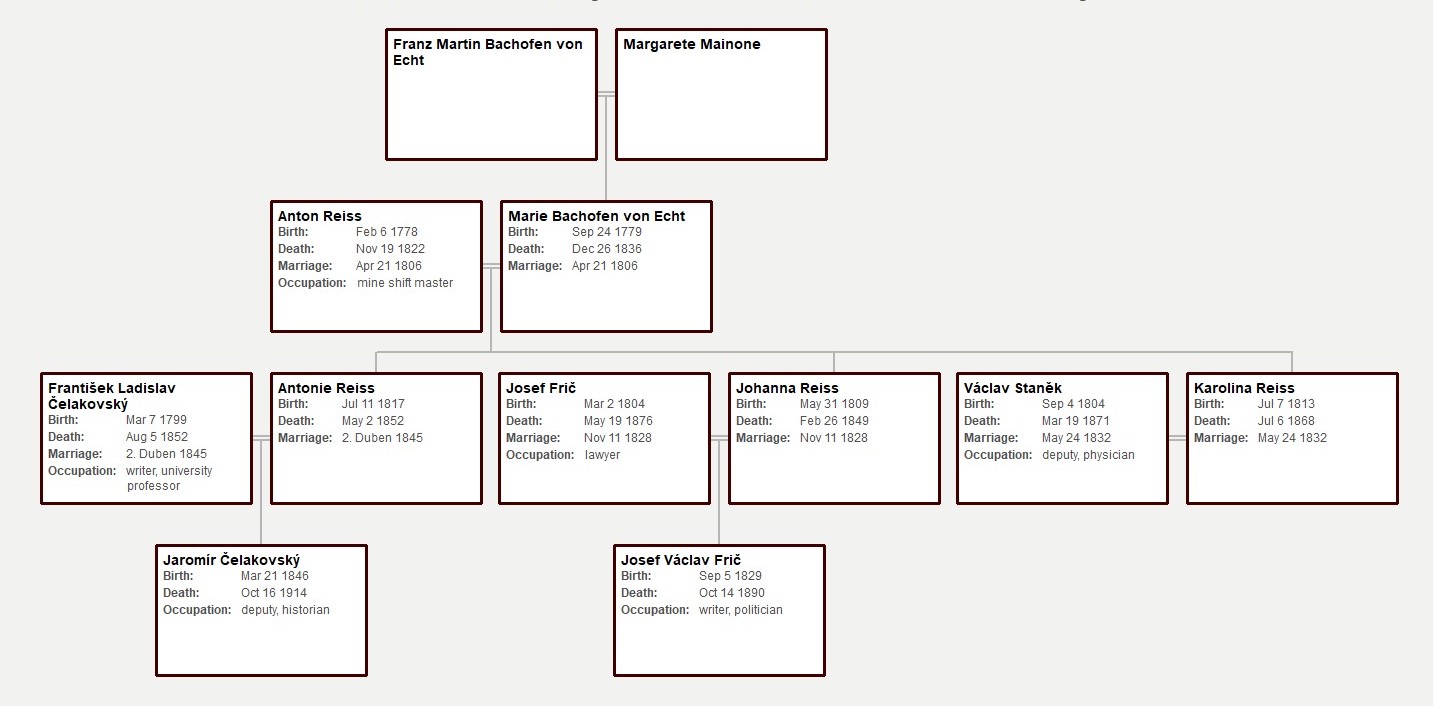

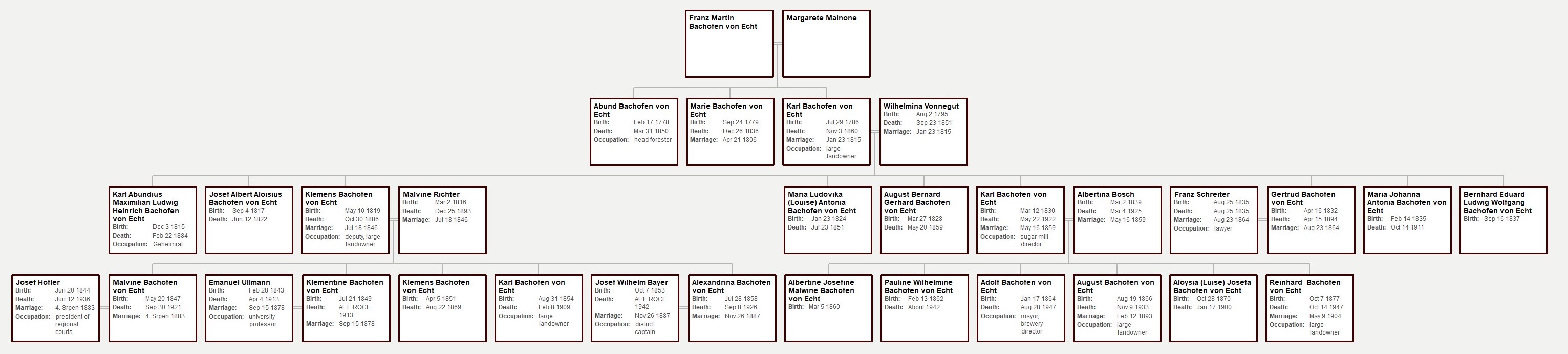

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

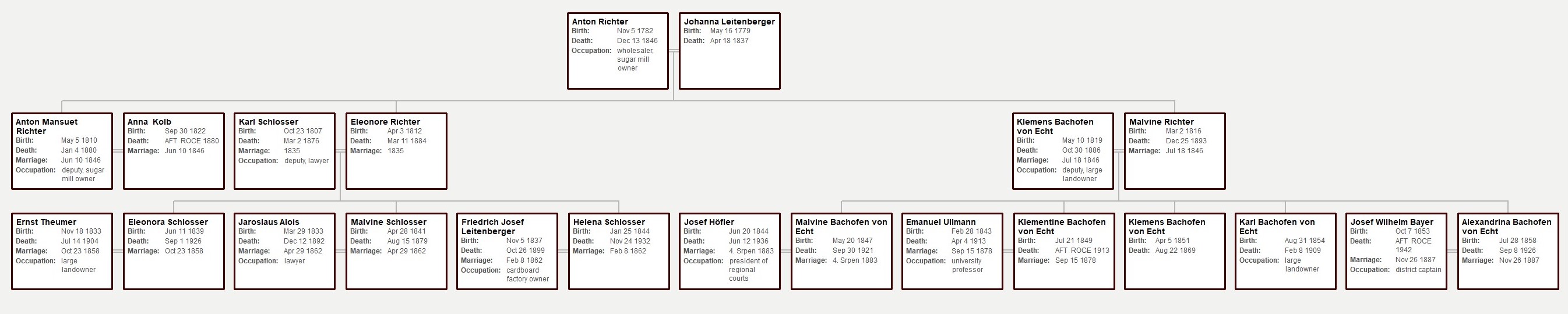

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

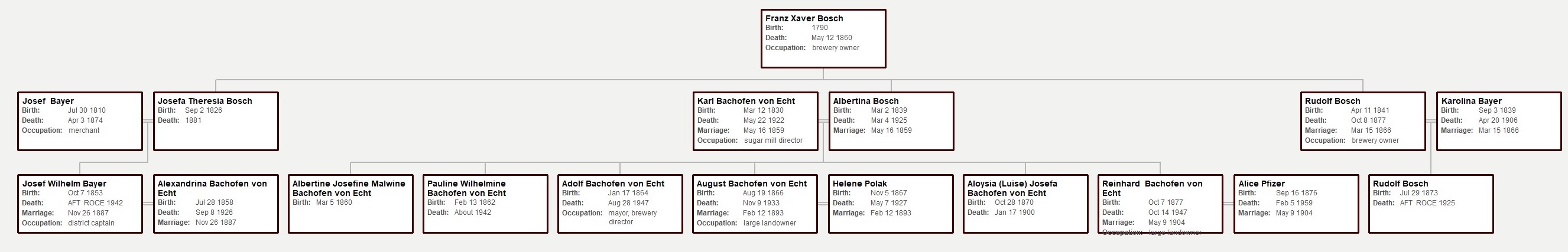

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

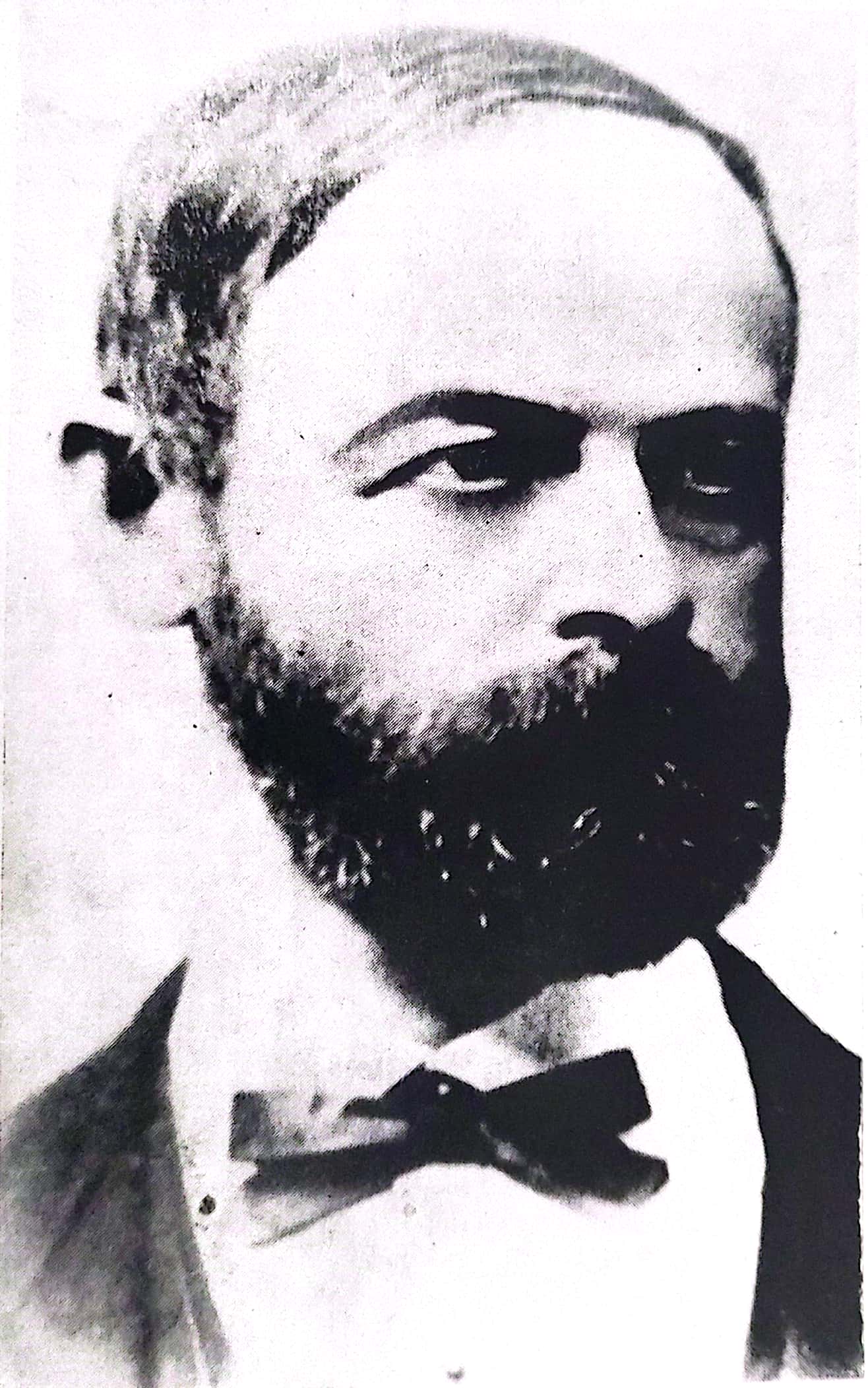

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

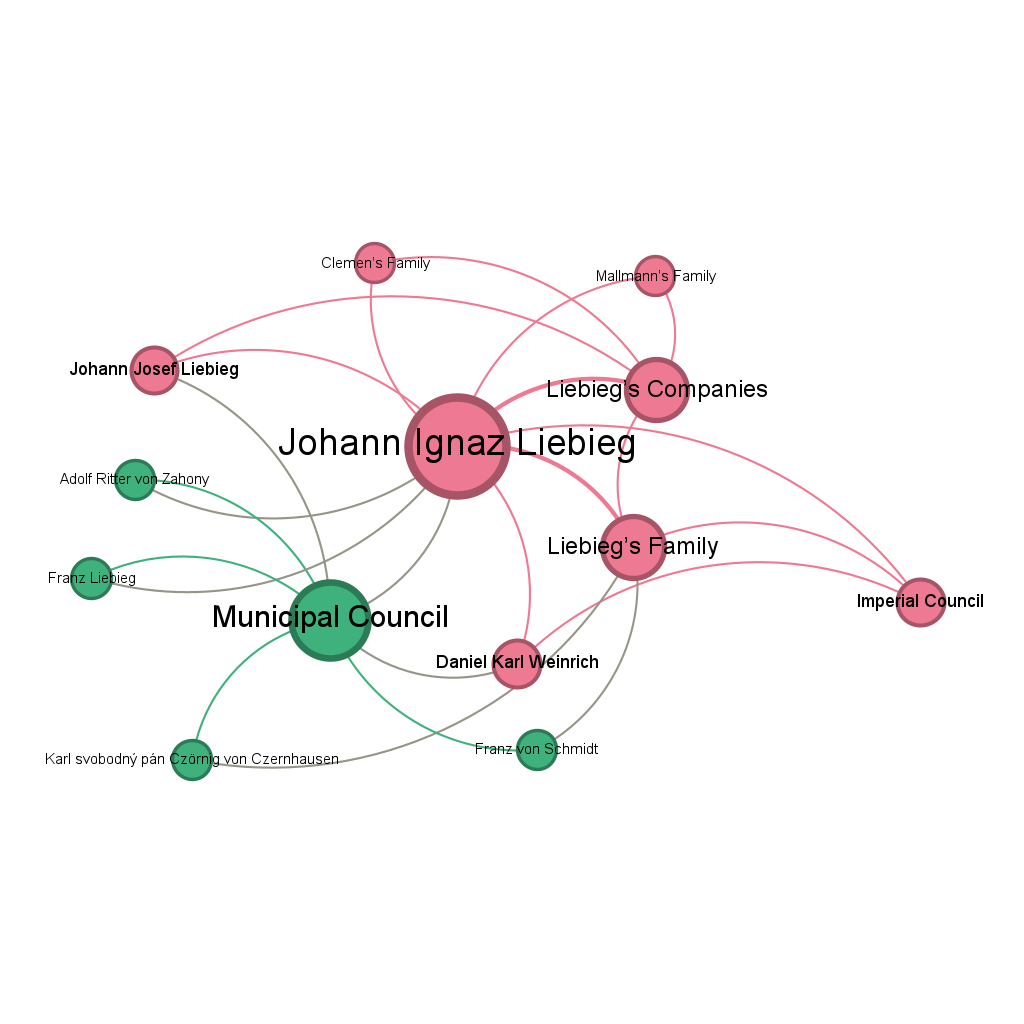

Family of Johann Ignaz Liebieg

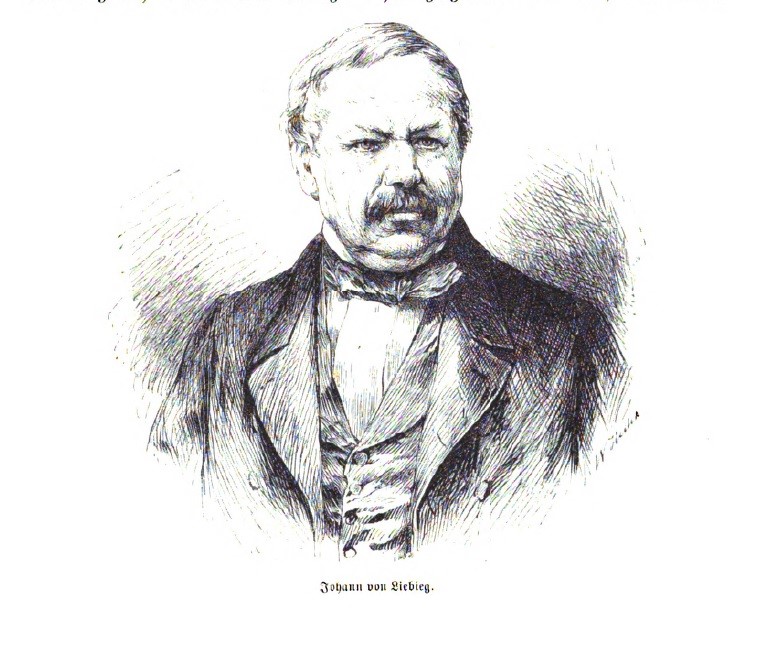

Johann Liebieg Österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, s. 661

Johann Ignaz Liebieg (1802–1870, newspaper entries of funeral and obituary) personifies one of the most successful businessmen and industrialists in the Habsburg monarchy of the 19th century. Johann Ignaz belonged to the so-called Gründer generation; in cooperation with his brother and other family members, he managed to build a huge textile empire in the Liberec region, which lasted for several generations, surviving the turbulent periods of workers' strikes, economic crisis and both world wars. Johann Ignaz Liebieg became involved in public life at the beginning of the 1850s as a co-founder and leader of the Liberec Chambers of Commerce, co-founder of the Liberec Savings Bank, between 1851–1859 he was president of the Liberec Chambers of Commerce and Trade and in 1851–1864 a city representative. In the 1960s, his public representative activities led to the highest councils - he sat in the Bohemian Diet and in the Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna for the curia of Czech cities. However, he ended his political engagement after three years by relinquishing his mandate. Johann Ignaz Liebieg was primarily a factory owner and entrepreneur. He devoted his life to taking care of the family business to ensure a better livelihood for his children. In 1868, Johann Ignaz Liebieg was elevated to the hereditary status of free lords for his services to the upliftment of industry.[1]

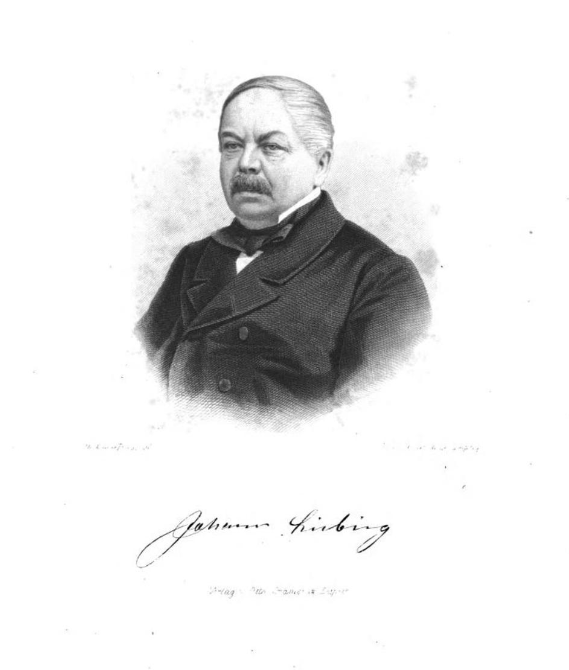

Johann Ignaz Liebeig Ein Arbeiterleben Geschildert von Einem Zeitgenossen

Arms of Liebiegs

Johann Ignaz Liebieg was born into the family of Franz (1769–1811), a Broumov burgher, draper and merchant. Textiles also had a tradition in the Liebieg family. Already Johann Ignaz's great-grandfather was a burgher from Broumov and made his living as a braider, and his grandfather Joseph Liebieg was a cloth merchant. Johann's other two siblings lived to adulthood, the first-born Franz Joseph (1799–1878) and their youngest sister Pauline (1808–1883). The father died prematurely when the eldest Franz Josef was 12 years old, and the mother was responsible for the upbringing of the children. Her relatives occasionally helped her with her three offspring in Broumov. Johann Ignaz was apprenticed to the Broumov master weaver and friend of his late father, Kaspar Werner, and then spent several months as a journeyman travelling "for experience". In 1819, Johann Ignaz settled in Liberec, where he was later joined by his older brother. The two siblings ran a small goods shop, in which their sister Pauline also helped them. Thanks to Franz Josef's experience and thrift, Johann Ignaz's business talent and innovative ideas, as well as the right selection of goods, the brothers were able to expand their shop and warehouses. Soon they also bought their first factory and the family business gradually began to expand.[2]

Johann Ignatz Karl Liebieg

Johann Ignaz Liebieg subordinated one of their business strategies, marriage policy, to the successful family business. In August 1832, at the age of 30, Johann Ignaz Liebieg married Maria Theresa Münzberg (1810–1848), the daughter of a merchant and textile manufacturer from Jiřetín pod Jedlovou.[3] Her father, Anton Münzberg (1765–1823), owned a linen, cotton and woollen goods factory. In 1820 he built a family villa in Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, connected with a complex of factory buildings.[4] Johann Ignaz invested the considerable dowry brought into the marriage by Maria Theresa in the expansion of his business.[5] Maria Theresa died at the age of 38 as a result of pulmonary paralysis, leaving behind a widower, Josef Ignaz, with nine[6] children.[7] In 1853, less than five years after his wife's death, Josef Ignaz remarried. His second wife was Marie Ludovica (1830–1891), née Jungnickel, granddaughter of Anton Münzberg.[8] Four sons were born to Johann Ignaz from his second marriage.[9]

Johann Liebieg

Johann Ignaz built a large family in the style of the Austrian Biedermeier. On the one hand he strove to provide for his family by expanding his business, on the other hand, he prudently ensured the continuity of the family company.[10] Johann Ignaz Liebieg married five daughters (the eldest, Maria Paulina, never married) and four sons (two of whom married after their father's death). No correspondence has survived in the family archives that sheds light on the Liebieg children's choice of partners. It can be assumed, however, that these were 'good catches' for all involved (the Liebigs), who had the potential to preserve and expand the family fortune, to advance up the social ladder, and were personalities with undeniably interesting contacts and access to information. The partners of Liebieg's descendants were either businessmen involved in the family business or landowners and politicians with influence at local or provincial level. At the same time, joining the Liebieg empire may have offered some partners an extension of their own business activities within the Habsburg monarchy.

Maria Theresia Münzberg Maria Luisa Jungnickel

Members of the two German merchant families Mallmanns and Clemens joined the Liebieg family business after their marriage. Both families came from the Rhineland, the Mallmanns from Boppard and the Clemens from nearby Koblenz. Josef Mallmann, the husband of Adelina Liebieg,[11] traded overseas, and in Paris he and his brother Gerhard (and husband of Adele's sister Hermine) ran the export firm Mallmann et Co. The Mallmann brothers had business contacts in Europe, South and North America, the Caribbean, India and China. After his marriage to Adelina, Joseph Mallmann became a partner in Liebieg's company and took over the management of its Vienna branch. In addition to his many business activities, he also served as president of the South-North German Connecting Railway (between Pardubice and Liberec) and the Austrian North-Western Railway (Děčín-Vienna connection).[12] Josef Mallman became an Austrian citizen and for his services he was knighted in Austria.[13]

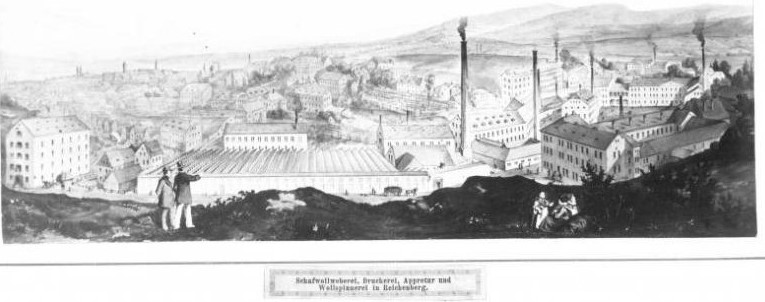

Factory of Johann Liebieg

Liebieg's son Theodor (1840–1891) married Angelika Clemens (1847–1919), daughter of the merchant and banker Johann Peter Clemens from Koblenz. Theodor Liebieg belonged to the second generation of Liebigs who inherited and managed the North Bohemian textile empire. After his marriage to Angelika, his two brothers-in-law, Gisbert and Leo Clemens, joined the management of the company.

In addition to merchants and businessmen, as mentioned above, the Liebieg family included landowners with representation in the land diets and the Austrian Imperial Council. Adolf Ritter von Zahony (1833–1907), the owner of the farm and castle in Bohemia and husband of Leontina Liebieg, sat in the Bohemian Diet.[14] Ritter von Zahony sat in the Landowners' Curia for the Party of the Constitutional Landowners (1872–1883). Daniel Weinrich (1843–1926),[15] husband of Marie Liebieg and owner of an estate in Bohemia, also held a seat in the same curia and party. In 1872–1883 and 1901–1907 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Diet for the Landowners' Curia, and later a member of the Imperial Council (1873–1878), where he represented the Party of the Constitutional Landowners.[16]

At the Austrian diets were: Bertha Liebieg's husband, Karl Reichsfreihrer von Gagern (1846–1923). Karl von Gagern was a member of the Upper Austrian Diet for the Landowners' Curia. Von Gagern served in the diplomatic service and was appointed Legation Councillor in The Hague in the late 19th century.[17] Leopold Mayr, a builder, architect and vice-mayor of Vienna, was also a member of the Lower Austrian Diet. Leopold Mayr was the father-in-law of Johann Josef Liebieg (1836–1899).

From the point of view of social networking, not only those marriages of Johann Ignaz's children that were contracted and where his business acumen was evident are of interest, but also those that did not take place. One example can be reconstructed. Johann Ignaz's step-aunt Franziska and her husband Peter Fügner imagined for their children a career similar to that of the Liebieg brothers."Johann Liebieg (1802–1870), the founder of the famous Liberec factories, was a role model for both his father and mother, and they made no secret of their wish that their son Jindřich would either show similar business agility to their relative or at least marry into the family of this famous Liebieg."[18] In the end, however, Jindřich Fügner (1822–1866) showed neither "liberalistic energy and fierceness" nor interest in becoming part of the Liebieg clan.[19] He found his niche in physical education and became one of the founders of the Czech gymnastic association Sokol. According to surviving reports, the marriage of Jindřich Fügner to the Liebieg's eldest daughter, Maria Paulina, was probably considered. The family's interpretation of events in the memoirs of Fügner's daughter Renata Tyršová gives the impression that the emotional Jindřich did not want to be part of the predatory and expanding Liebieg empire. On the other hand, it is worth considering that he was not chosen by Johann Ignaz Liebieg. In fact, the same source describes the beginnings of the business career of Jindřich Fügner, who, although had travelled extensively in Europe and supplemented his education with a private tutor in Prague, had no entrepreneurial spirit and no desire to become involved in business in any way. For Johann Ignaz Liebig, he could not have been the ideal partner to whom he could later hand over a share in the family business.

From the point of view of social networking, not only those marriages of Johann Ignaz's children that were contracted and where his business acumen was evident are of interest, but also those that did not take place. One example can be reconstructed. Johann Ignaz's step-aunt Franziska and her husband Peter Fügner imagined for their children a career similar to that of the Liebieg brothers."Johann Liebieg (1802–1870), the founder of the famous Liberec factories, was a role model for both his father and mother, and they made no secret of their wish that their son Jindřich would either show similar business agility to their relative or at least marry into the family of this famous Liebieg."[18] In the end, however, Jindřich Fügner (1822–1866) showed neither "liberalistic energy and fierceness" nor interest in becoming part of the Liebieg clan.[19] He found his niche in physical education and became one of the founders of the Czech gymnastic association Sokol. According to surviving reports, the marriage of Jindřich Fügner to the Liebieg's eldest daughter, Maria Paulina, was probably considered. The family's interpretation of events in the memoirs of Fügner's daughter Renata Tyršová gives the impression that the emotional Jindřich did not want to be part of the predatory and expanding Liebieg empire. On the other hand, it is worth considering that he was not chosen by Johann Ignaz Liebieg. In fact, the same source describes the beginnings of the business career of Jindřich Fügner, who, although had travelled extensively in Europe and supplemented his education with a private tutor in Prague, had no entrepreneurial spirit and no desire to become involved in business in any way. For Johann Ignaz Liebig, he could not have been the ideal partner to whom he could later hand over a share in the family business.

Johann Ignaz prepared his children for a very different entry into life than he himself had. His descendants received a private education and the opportunity to study at foreign universities, inherited a noble title, social status and a fortune estimated at 30 million guldens in his time. Each handled their inheritance differently, according to their own values and individual convictions. However, one can observe a continuity of ties to foreign businessmen and merchants and a striving for inclusion in higher noble society. From the point of view of maintaining the family business, Johann Ignaz did everything possible to ensure that the transfer to the new generation went smoothly. Coincidentally, in the third generation, the company passed to his grandson Theodor Liebieg (1872–1939), who ran it successfully for almost 50 more years. Political reasons finally deprived the heirs of the Liebieg empire of all their property in Bohemia (worth 140 million Czechoslovak crowns) in the 1940s.

[1] National Archives, ČZS, ka. 201, 201b, fol. 657, Liebieg Johann.

[2] Např. ANSCHIRINGER, Anton: Johann Liebieg. Ein Arbeiterleben Geschildert von Einem Zeitgenossen. Leipzig: Verlag von Otto Spamer, 1871; Franz Liebieg. Wien: Selbst-Verlag, 1873; Allgemeine deutsche Biographie. Bd. 18, Lassus – Litschower. Leipzig: Duncker&Humblot, 1883; MALÝ, Jakub. Stručný všeobecný slovník věcný: (malý slovník naučný). Díl VIII. V Praze: I. L. Kober, 1884, s. 168; MERAVIGLIA-CRIVELLI, Rudolf Johann. J. Siebmacher’s Großes und Allgemeines Wappenbuch. IV/9. Der Böhmische Adel. Nürnberg 1886, s. 77, Taf. 48; ERSCH, Johann Samuel. Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetischer Folge. Zweite Section. H–N. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1889, s. 372–374; PETHES, Justus. Gothaisches genealogisches Taschenbuch der freiherrlichen Häuser. Dreiundvierzigster Jahrgang. Gotha 1893, s. 518–520; Ottův slovník naučný: ilustrovaná encyklopaedie obecných vědomostí. Část 15. V Praze: J. Otto, 1900, s. 1051; WIESINGER, Udo B. "Liebieg, Johann Freiherr von". In: Neue Deutsche Biographie, 14 (1985), s. 493–494 [online]. Dostupné z: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd137847602.html#ndbcontent (cit. 26. 6. 2022). Dále např.: SCHILLER, Karl. Umrisse einer allgemeinen Geographie: mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Oesterreich. Umrißeeiner Handels-Geographie für Deutschland und insbesondere Oesterreich: mit einschlagender Lectüre. Zweiter Theil. Wien: Druck von Anton Schweiger, 1864. s, 84–87; RESSEL, G. A.: Nordböhmisches Industrie-Album: die Stättenheimischer Arbeit in Wort und Bild. I. Heft. Teplitz: Im Selbstverlag, 1874, s. 3–14; Die Österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild. Böhmen (2 Abtheilung). Band 15. Wien: K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1896, s. 660–662; RESSEL A.: Verdiente Männer aus Ostböhmen als Wappenerwerber. In: Jb. d. Dt. Riesengebirgs-Ver. f. d. J. 1927, 16. Jg., 1927, s. 24-58. Z novějších prací: RANDÁK, pozn. 1, BERGMANNOVÁ, pozn. 2, HLAVÁČ, Miroslav M. Tvůrci českého zázraku. Praha: APS Agency, 2000, s. 111–114; MYŠKA, Milan. Historická encyklopedie podnikatelů Čech, Moravy a Slezska do poloviny XX. století. Ostrava: Ostravská univerzita, 2003, s. 273–278. Franz Liebieg, pozn. 3; ERSCH, Johann Samuel. Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetischer Folge. Zweite Section. H–N. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1889, s. 372–374.

[3] State Regional Archives in Litoměřice (hereinafter referred to as SRA Litoměřice), Roman Catholic Parish Office (hereinafter referred to as FÚ) Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, Register of Marriages 1784–1840.

[4] National Heritage Institute, Monument Catalogue, Vila Antona Münzberga. [online]. Available from: https://www.pamatkovykatalog.cz/vila-antona-munzberga-15548297 (Cited 26. 6. 2022).

[5] MYŠKA, Note 2, p. 274.

[6] Josef Ignaz Liebieg and Maria Theresia Münzberg had a total of 11 children, two of whom died a few months after birth: first-born Ludwig (*† 1833), daugter Ida (1844–1845).

[7] SRA Litoměřice, FÚ Liberec, Register of Deaths 1824–1848.

[8] SRA Litoměřice, FÚ Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, Register of Marriages 1841–1876. Anton Münzberg married three times in total. From the first marriage in 1787 14 children were born, in 1800 twins, one of them was Francisca, later married to Johann Jungnickel. With his second wife Anton Münzberg had a daughter Maria Theresia, married in 1832 to Johann Liebieg. At that time, her older half-sister Francisca already had a two-year-old daughter Maria Ludovica Caroline, the future second wife of Johann Ignaz Liebieg. Liebieg thus married first Anton Münzberg's daughter from his second marriage and then his granddaughter from his first marriage.

[9] Of his four sons from his second marriage, died in infancy Oscar (*1855–†1856).

[10] HLAVAČKA, Milan a BEK, Pavel. Rodinné podnikání v moderní době. Praha: Historický ústav, 2018. p. 26–29.

[11] SOA Litoměřice, FÚ Liberec, Register of Marriages 1848–1861.

[12] MARSCHNER, Erhard. Mallmann, Josef Ritter von. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 15, Duncker&Humblot, Berlin 1987, p. 737.

[13] MARSCHNER, Erhard. Mallmann, Josef Ritter von. In: NeueDeutscheBiographie (NDB). Band 15, Duncker&Humblot, Berlin 1987, p. 737.

[14] Die Arbeit, 1907, 14. Jahrgang, No. 981 (4. August 1907), p. 4.

[15] Weinrich, Daniel Karl (Karl Daniel)“. In: Republik Österreich Parlament [online]. Available at: https://www.parlament.gv.at/WWER/PARL/J1848/Weinrich.shtml (Cited 14. 7. 2022).

[16] WURZBACH, Constantin von. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthum Oesterreich. Wien: Druck und Verlag der k. k. Hof – und Staatsdruckerei, 1886, p. 58–61.

[17] (Linzer) Tages-Post, 59. Jahrgang, No. 8 (12. Jänner 1923), p. 4.

[18] BARTOŠ, Josef. Vývoj osobnosti Jindřicha Fügnera. Sokol, 1933, Year. 59, No. 12, p. 258–264.

[19] TYRŠOVÁ, Renata. Jindřich Fügner: paměti a vzpomínky na mého otce. Part 1. Praha: Český čtenář, 1924, p. 30.