In the 1930s, the Nica family had two sons and five daughters. My grandmother, Elena (b. 1938), was the youngest and the only one still living. The boys of the Nica family were encouraged to study, and both became state employees after 1944. The girls, on the contrary, only pursued school for less than a year: for the future meant marrying someone from Florica with enough land to ensure the new families’ survival.

Aurel, my grandfather (b. 1936), was the sixth and the last born in the Dumitrescu family from Gheraseni, 20 kilometers north across the field from Florica, not far away from Buzău. In the interwar period, the Dumitrescu family, Stoica and Leonora, was a wealthy peasant family and owners of a local tavern. Still, when Leonora, Aurel’s mother, died, the father and grandfather (the family’s chief) decided to give the six-month-old Aurel for adoption to the Sora’s family. The new family showed Aurel all the love a couple could offer. At the age of 14, Aurel got to know his natural family. The ties between Aurel and his biological family remained now very close.

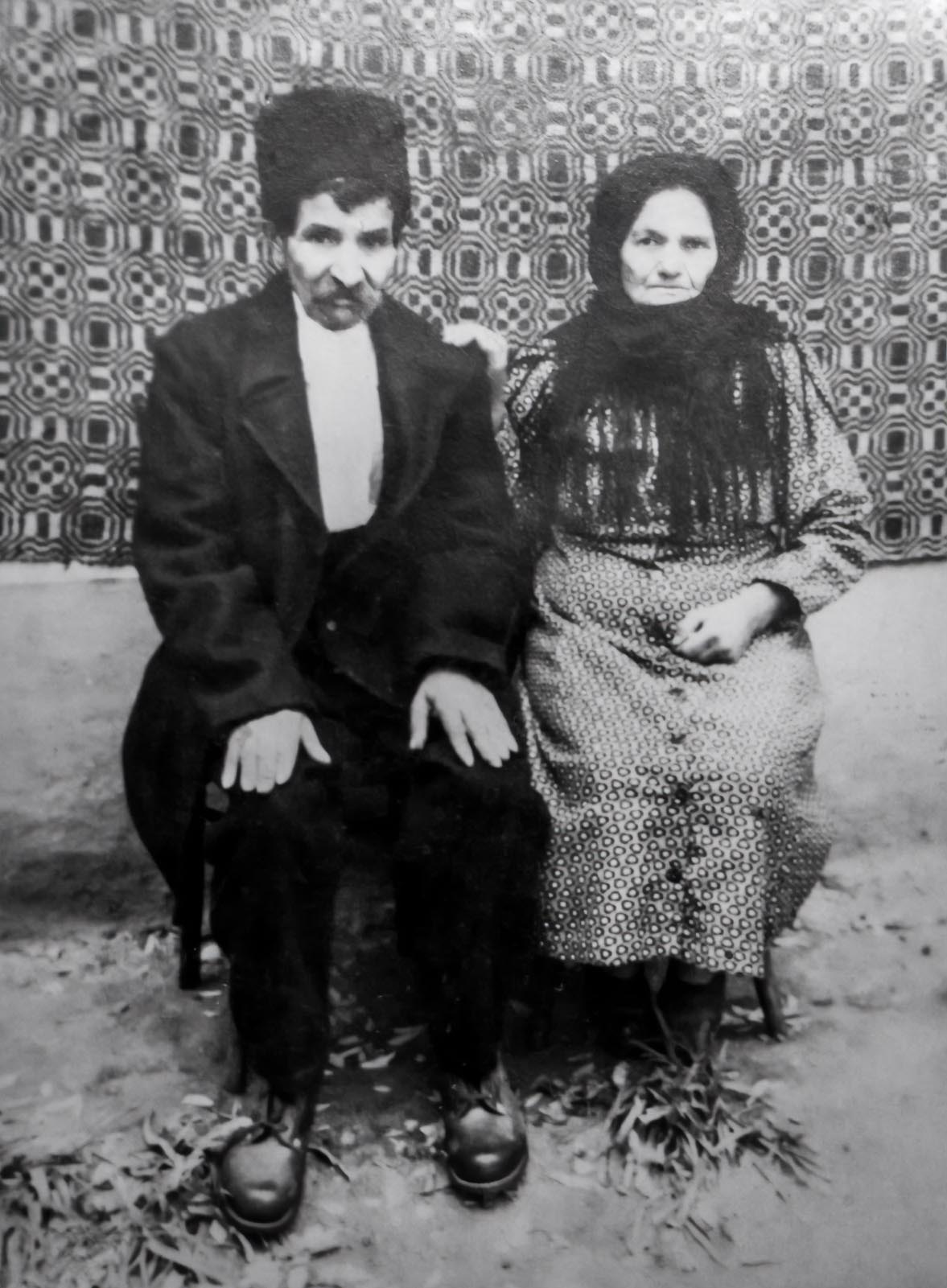

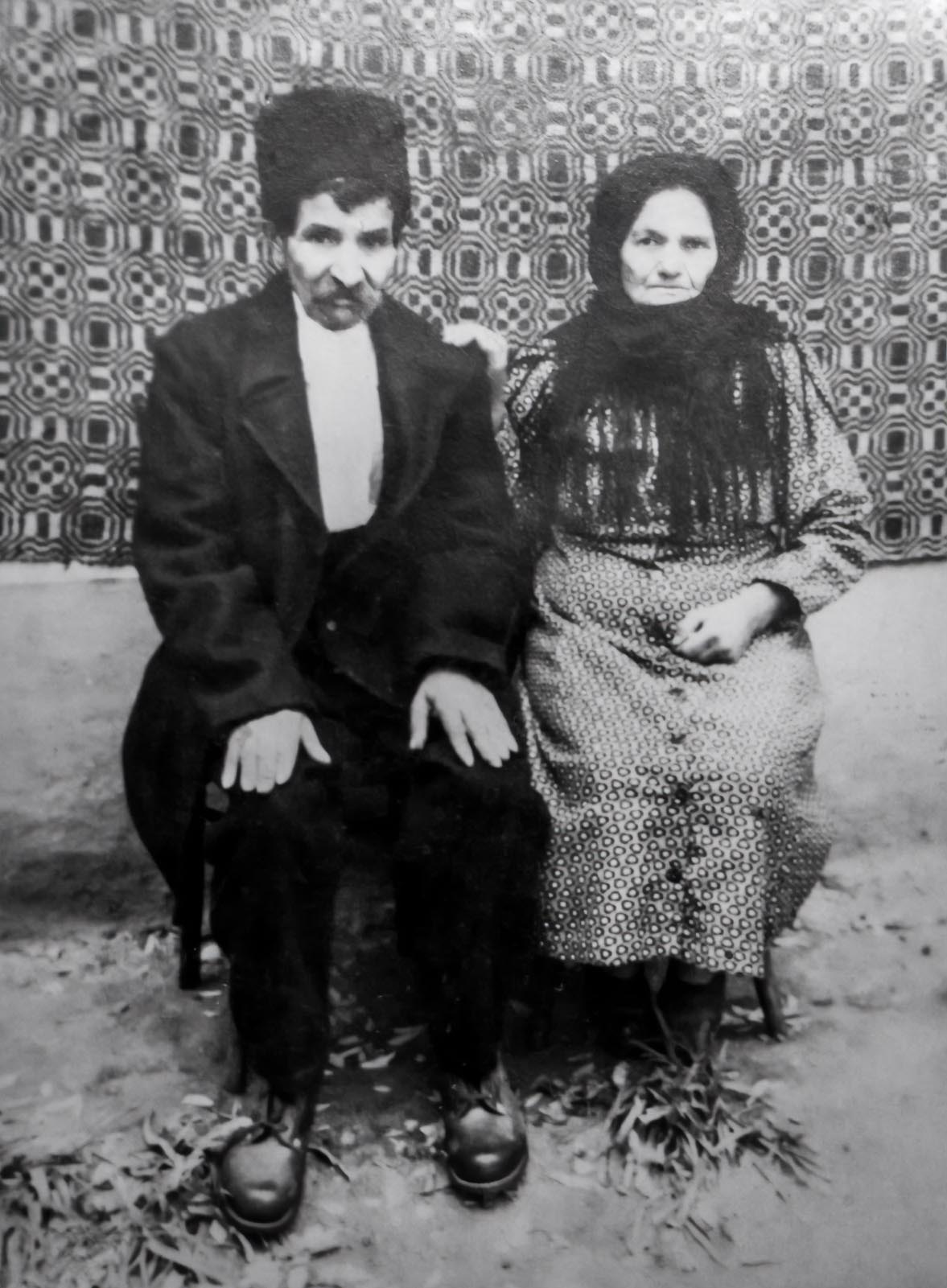

Maria and Gheorghe Sora, 1950s

Maria and Gheorghe Sora, 1950s

Aurel, 19 years old, fell in love with Elena, 17 years old, at the Sunday dance, after the church service. Both families disagreed with this relationship. With her consent, Aurel stole Elena: in 1956, my father Valerică was born, and a few years later two sisters followed.

Elena and Aurel Sora, 1955

Valerică and his grandmother Maria Sora

After the collectivization in Florica, Aurel and Elena worked together at the village cooperative; the parcel around the Sora house helped them to have a better life. At the end of 1960, Aurel decided to do the same as hundreds of thousands of Romanian peasants in the communist period: move to the city. Initially, he worked in a forge and lived in barracks with more than fifty beds. After obtaining a better and less complicated job (as a stoker), his wife and two daughters followed him to Bucharest. By then, my father, at the age of 17, had already finished professional school in Bucharest and had a job as a tool-making turner. He believed that he could succeed more, and he chose to pursue a career in the Militia (police), from the ground to the top: as a student of the Police School, as a non-commissioned officer, and then officer after the completion of the Officer School. As a sergeant, in 1978, in Bucharest, he met my mother.

Jeni and Valerică (University’s Square, Bucharest, March 1978) - one of their first encounters

My mother was born in Mosna, in Moldavia, 52 kilometers from Iași, known for an archeological site and its quinces trees. Her father, Ion Radu (b. 1921), remained an orphan from age two, and his father had little land. My grandmother’s family was originally from Schitu Duca, a village 25 kilometers away, and came to Moșna at the beginning of the 20th century. For that reason, the family received the official name of Duca. My grand-grandfather, Mihai Duca, a tinsmith, worked at the construction of the roofs of many churches. He also believed that learning a craft would be a valuable asset. For that reason, one of his daughters, Eleonora (b. 1922), who had lived for three years (until the age of 15) in a Jewish family from the nearest borough (Raducaneni), learned tailoring and how to behave in bourgeois society. Without her mother’s consent, Eleonora married Ion, even though he had no fortune and was called to fight in the Second World War. The tailoring helped the family survive, an additional source for six sons and daughters, the youngest being my mother, Jeni (Jănița). Five of them attended professional schools, and Jeni (b. 1957) finished secondary school: at the High School of Art from Iasi. Only one son remained in the hometown with his parents. All three sons worked in agriculture. For them, the social mobility provided by the communist period was not assured except to a small extent. On the other hand, the sisters moved to Bucharest.

Ion and Eleonora Radu with their young children: Angelica and Jeni

Jeni (front row, third from right) at the primary school in Mosna, 1967

Similar to the other two sisters, Jeni arrived in Bucharest in 1976. She dreamed of pursuing her dream of becoming an artist, but she failed the entrance exam at the Faculty of Arts. The only remaining option was to work in one of the few places in Bucharest that, at that time, legally accepted employees without their residence in Bucharest. In 1979, she succeeded in using her artistic skills to work as a drafter at the Institute for the Study and Design of Communal Households.

My mother and father’s families were not victims of communist oppression as hundreds of thousands of other families. One reason is that they were not rich, and they avoided entering the conflict with the new communist regime. Furthermore, they capitalized on the economic and social changes after the Second World War: the massive alphabetization (including young girls), internal migration, and industrialization. It is hard to tell if the communist period contributed to their social mobility and whether a democratic regime could not have offered better opportunities for Sora and Radu families.