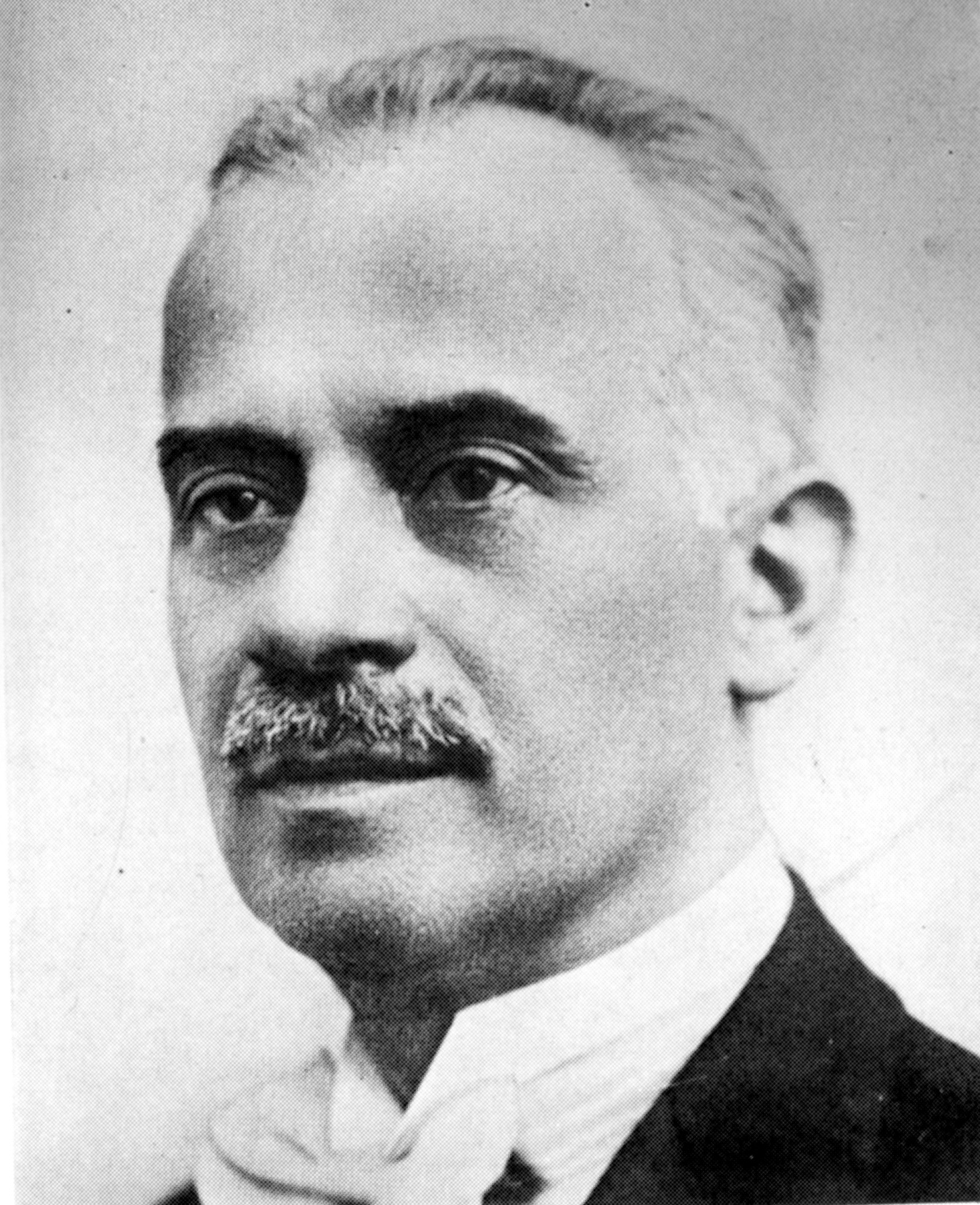

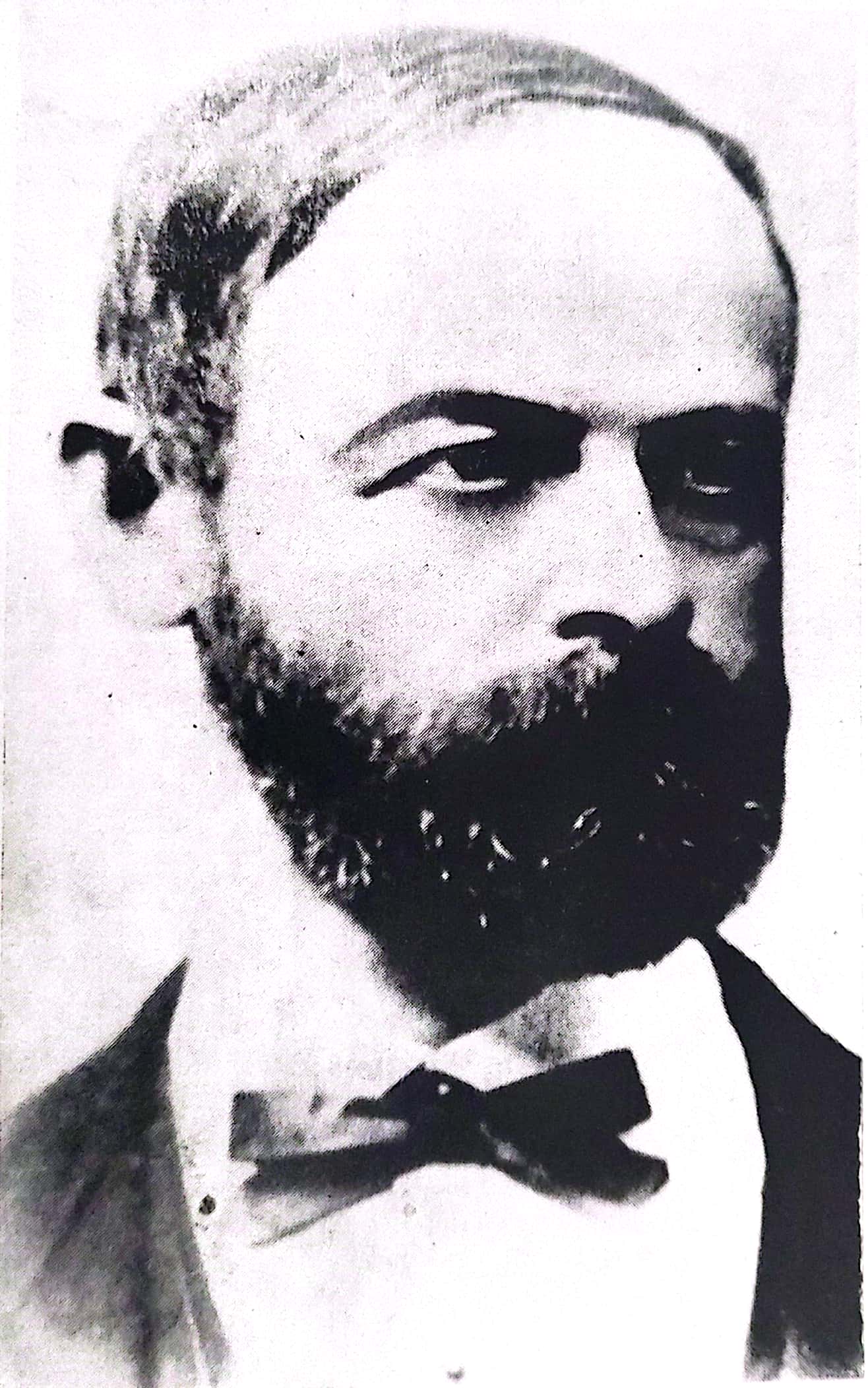

Anton Julius Gschier (1814–1874), lawyer, deputy and mayor

The possibility to penetrate among the political elite of the Habsburg Monarchy in the latter half of the 19th century was significantly influenced by the institutional structure of the Empire and the way in which representatives at various levels of self-government were selected. From the middle of the century, when the first elections to the Imperial Council took place in 1848, and in the following decades, until the electoral reform in 1907 introduced universal suffrage for men, the electoral districts for both the provincial and imperial parliament were usually territorially rather small, always covering only a few neighbouring towns or districts. Especially in the provincial diets electoral districts of the municipal curia in Bohemia often included one town or two towns.

Postcard from Cheb from the nineteenth century.

Within Bohemia, the region of Cheb/Eger, with its natural centre in the town of Cheb, was rather specific. The revival of public life in the spring of 1848 brought with it calls for the restoration of an independent status of the region or even the return of the territory to the Empire. This was also the reason why Cheb citizens refused to elect their representatives to the reformed Bohemian Diet on the grounds that they did not recognise this assembly as their representative body. It is in this context that Anton Julius Gschier, a Cheb native and lawyer, who in the 1840s worked as a Justiziar (official endowed with judicial powers) on the surrounding estates, soon established himself as one of the main spokesmen of the exclusively German speaking Cheb bourgeoisie.

Gschier was born into the family of a Cheb municipal official whose wife was the daughter of one of the first Cheb mayors of the so-called regulated municipal office. Jeremias Gschier (1783–1841) and his wife had only one son, the aforementioned Anton Julius, born on 19 December 1814, more than five years after their wedding. No other children could be traced, nor do they appear on Jeremias’ death notice of 1841. Even so, the clerk’s family was unable to fully provide for their only son’s studies, so Anton was supported by a scholarship intended for the children of Cheb’s burghers.

One year after his father’s death, the young Gschier married the daughter of a local post supervisor and later administrator of the state postal service. No other significant family or kinship ties could be found in the sources available. The key moments shaping his career were the events linked to the abolition of patrimonial administration and the revival of public life in 1848–1849. As a doctor of law and representative of the educated bourgeoisie, Gschier was one of the chief organisers of the burghers’ assemblies that prepared petitions addressed to the Emperor and the government. However, his views apparently clashed with those of the majority of Cheb bourgeoisie representatives. While these venerable patres looked more towards the past and aimed to restore the special status of the town and its surroundings within the Habsburg Empire, Gschier was a progressive and liberally oriented representative of the new intellectual elites. Among other things, he advocated, albeit unsuccessfully, the sending of Cheb representatives to the provincial assembly in Prague. Later, he even recognised the usefulness of optional Czech language instruction at the local grammar school. His views as well as his apparently very uncompromising and vigorous discourse were the reason why he was not as widely recognized and accepted as other local personalities such as the local pharmacist Adolf Tachezi (1814–1892) or the burgher Franz Ernst.

It was the preparation of a petition containing the demands of the town that caused a split in the burghers’ committee elected in March 1848, with Gschier as president. Gschier had vigorously opposed the idea of Cheb’s own Diet or a new convocation of the Cheb Estates, and resigned from the committee in April. Despite his liberal views, still in 1851 Gschier obtained the post of barrister in Cheb, securing thus a permanent presence in the town. By then, Cheb had become a major administrative centre and the seat of new state offices: the district captainship, the regional government, the regional and district court, the grammar school and the chamber of commerce and trade. It was the latter institution that later chose Gschier as its secretary. This post guaranteed him a regular salary, in addition to the income from his legal practice. It also provided him with a range of contacts with like-minded liberal representatives of local industry and commerce.

At the turn of 1851 and 1852, the neighbouring town of Františkovy Lázně was definitively excluded out of the cadastre of the Cheb municipality. As a result, new elections of the municipal self-governing body in line with Stadion’s provisional municipal law could take place. Although Gschier became a member of the municipal committee, his election was not unanimous, and definitely not as unambiguous as that of some other candidates. He received 90 of the 179 votes cast and in the end was not even selected into the more restricted body of councillors, which included a local brewer, a chemist, a doctor and two merchants.

In 1855, Gschier became a town councillor after some members of the committee resigned. Unfortunately, we do not know the exact reasons which brought Gschier back as a leading representative of the Cheb bourgeoisie. It could have been his involvement in the chamber of commerce, his work in the town, where he was one of only three barristers, or his renewed willingness and readiness to participate in the running of public affairs. He immediately began to push his ideas on how the town should function. Among other things, he put through the construction of walking paths and gazebos around the town. He also supported the reconstruction of the St. James Brotherhood Home, a traditional Cheb institution where the poor and old townspeople could live their last years in dignity.

At the beginning of the 1860s, conditions in Austria began to change. The financial crisis, compounded by the disastrous debacle of the Austrian army in northern Italy, forced the Emperor to accept constitutional reform. The renewed elections to the municipal committees confirmed Gschier’s position as one of the councillors and also – and more importantly – as the city’s representative in the newly constituted Bohemian Diet. Before election, Gschier presented himself publicly as a liberal candidate. He declared his support for industry and commerce, vocational education, and the status of municipalities as basic units of self-government. He had to tread carefully, however. Indeed, certain passages of his statement, published by the local newspaper, in which he calls for dampening of passions and setting aside personal interests, show that he was not universally accepted in the town.

As a liberal, he had a rather complicated position in Cheb. Unlike his colleagues and fellow liberal deputies, who strongly opposed the historical Bohemian state law and upheld the centralisation of the Empire, he realized the importance of the historical status of the town for his fellow citizens. Rejecting traditional rights and denying the specific status of the region would certainly not win him many votes. This is why he preferred not to mention this topic at all in his statement. In the end, also thanks to the absence of major opponents, he received 341 votes out of 349 ballots cast. The Bohemian Diet selected him as a member of the Imperial Council and Gschier became one of the representatives in the parliament in Vienna. Thus, in the mid-1860s, Julius Gschier’s political career reached its peak. He was both a provincial and imperial deputy, a city councillor and a member of the district council. At the same time, however, he was already fifty years old and apparently began to experience health problems. These forced him to give up his career as a deputy and return to the settled life of a Cheb burgher. For the candidates from outside Prague and Vienna, work in Parliament entailed frequent travel, staying in hotels, long periods without family or eating outside one’s home, which was not only uncomfortable and expensive, but also caused health complications for many deputies.

Despite that, Gschier did not completely retreat into seclusion. In September 1867, after the previous mayor Franz Ernst refused to continue in his office due to his old age, it was Gschier who was elected mayor by 31 votes out of 35. In his inaugural speech he said that he was at an age where he no longer desired public offices and positions. He also mentioned his health issues. He declared that he accepted the office of mayor only because of his unwavering belief in public life and its importance (Glaube an ein öffentliches Leben). Gschier remained in the office of mayor for two terms. Already in the first few months he proved to be a skilled organiser and a man with a clear vision. He reorganised the municipal office, reforming the functioning of the municipal committee and its specialised commissions. He also introduced new office regulations, revised the market regulations and increased the number of municipal policemen, raising their wages. He also had his own remuneration increased to 1,000 Guldens. At the end of his second term, however, he was progressively left with less and less energy. By 1873 he was virtually absent from the municipal committee meetings where he had to be replaced by the councillor Adolf Tachezy, who also became mayor at the next municipal elections. Anton Julius Gschier died shortly afterwards, on 30 June 1874.

Grave of the Gschier family in Cheb (Wikimedia Commons, author: SchiDD)

Gschier can serve as an example of an individual whose social advance was made possible by his abilities, education, ambition and suitable opportunities. As one of the few legally educated members of the bourgeoisie of the time, he managed to assert himself relatively quickly in the new "constitutional" setting of 1848. Although his belief that it was important to be publicly active and to influence public affairs brought him, on more than one occasion, into conflict with the traditional Cheb bourgeoisie, what ultimately prevailed were his rhetorical skills, his vision of the necessary reforms and the willingness to devote his time and resources to public issues. It is clear that in his public activities Gschier had to rely on the contacts and relationships he had built by himself in the course of his life, but which he could also pass on to his children.

Bibliography

Charmatz, Richard. Österreichs innere Geschichte von 1848 bis 1907: II. Der Kampf der Nationen. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1912.

Judson, Pieter M. The Habsburg Empire: A New History. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Sterneck, Tomáš. “Komplot pomstychtivého pleticháře? Ke kontroverzím vzniku českobudějovického regulovaného magistrátu v roce 1787 [A plot by a vengeful schemer? On the controversies of the establishment of the regulated municipality of České Budějovice in 1787].” Jihočeský sborník historický 89, no. 1 (2020): 73–120.

Šťouračová, Jiřina. “Reformní zásahy Marie Terezie a Josefa II. do městské správy na Moravě [Reform interventions of Maria Theresa and Joseph II in the municipal administration in Moravia].” Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity 50, no. 1 (2003): 169–76.

Velek, Luboš. “’Takový život nestojí za zlámanou grešli!’ Obrázky ze života českých poslanců 19. století [‘Such a life is not worth a broken penny!’ Pictures from the life of Czech parliamentary deputies in the 19th century].” Kuděj. Časopis pro kulturní dějiny 1, no. 2 (1999): 49–63.

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu (1876‒1942) ‒ a politician, writer and publicist

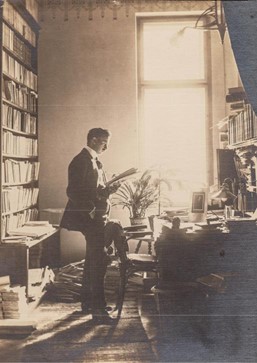

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Tăslăuanu

Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu was born on 1 February 1876 in the village Bilbor, Ciuc County. His father, Ioan Tăslăuanu (?–1927), was a priest, and his mother, Anisia Stan (1859–1933), came from a peasant family. Tăslăuanu attended secondary school in Năsăud (1889), Brașov (1890 –1892) and Blaj (1892–1895). Due to disagreements with his father about his career, as his father wanted him to become a priest, Tăslăuanu left for Bucharest in the Old Kingdom of Romania, where he worked as a teacher at a private school. At the same time, he continued his studies at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (1898–1902), supporting himself by teaching.

Taslauanu in his office

Taslauanu in his office

In 1902, on the recommendation of Ion Bianu (1856–1935), one of his professors and director of the Romanian Academy Library, he was appointed secretary of the Romanian Consulate General in Budapest. There, in addition to his duties, Tăslăuanu became involved with the magazine “Luceafărul”, first as a proofreader and later as an editor. Published successively in Budapest (1902 –1906), Sibiu (1906–1916) and Bucharest (1919–1920), “Luceafărul” promoted national culture and the political unity of the Romanians in Transylvania.

In his private life, in 1906, Tăslăuanu married Adelina Olteanu-Maior from Sibiu (1877–1910), who came from an old and prestigious family of intellectuals. She was also a writer and author of several books of children's stories. Godparents to their marriage were the family of Constantin Argetoianu (1871–1955), one of the most influential Romanian politicians of the inter-war period.

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina Taslauanu 1st wife of Octavian Taslauanu

Adelina with Octavian Taslauanu 1907

After the marriage, Tăslăuanu settled in Sibiu, where he served (until 1914) as an administrative secretary of the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People (ASTRA) in Sibiu. ASTRA was the most important and influential cultural and political association of Romanians in Transylvania.

From 1907, Octavian Codru Tăslăuanu took over the direction of the journal “Transilvania” (published by ASTRA), first as an editor and later as a director, transforming it into a true reflection of Romanian culture and science. His work was particularly fruitful, especially through the reorganisation of the ASTRA Popular Library, which included the monthly publication of a new volume of this collection, together with an annual calendar distributed to all the members of the branch, reaching almost every locality in Transylvania. Between 1911 and 1914, under his supervision, 49 issues within this collection were published, including various history books and anthologies of classical authors. The print run of a single issue reached 15,000 copies in 1912, with 11,861 sent to subscribers. However, this period was marked by the death of Adelina Tăslăuanu in 1910 from heart disease.

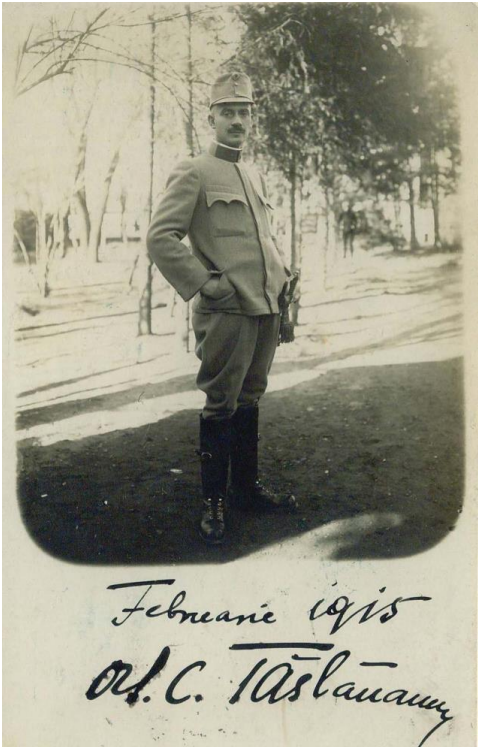

In 1914, Tăslăuanu was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army and sent to the front in Galicia, but he deserted to Romania and volunteered for the Romanian army, where he served in intelligence throughout the war. He became a Romanian citizen in July 1917 and was promoted to lieutenant and later captain.

Taslauanu as an officer

Taslauanu as an officer

In 1918, Tăslăuanu married Fatma Alisa Sturdza (1893–1964), whom he had met as a nurse at the front. She came from an old aristocratic family of politicians and large landowners. Tăslăuanu had two children: Ioan Radu (born 1920), who died at the age of one, and Dafina (1921–2000). Dafina's godfather was the Primate Metropolitan of Romania, Miron Cristea (1868–1939).

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu also had a remarkable political career. In the parliamentary elections of November 1919, he was elected deputy of Tulgheș, standing for the People's League. In the government led by Alexandru Averescu (1859–1938), he served as Minister of Trade and Industry (13 March – 16 November 1920) and Minister of Public Works (16 November 1920 – 1 January 1921). In these roles, he initiated a number of important laws and reforms for the reorganisation of the national economy in the post-World War I period. His achievements include the establishment of the explosives factory in Făgăraș, the nationalisation of the Reșița factories, the organisation of the oil industry through the creation of the Romanian Oil Industry, the drafting of laws for the monopolisation of the oil trade and the organisation of the grain trade, the founding of the Polytechnic University of Timișoara and the securing of funds for the construction of the Commercial Academy in Bucharest. Between 1926 and 1927 he was senator for Mureș, where he proposed the participation of Romanian parliamentarians in the first Pan-European Congress in Vienna.

Octavian Tăslăuanu died in Bucharest on 22 October 1942. His career is remarkable, considering that he rose from the position of a rural priest's son to that of a parliamentarian and minister. He achieved this primarily through personal merit, but also by successfully building social connections with influential families, first through his marriage to Adelina and later to Fatma. Unlike him, his brothers Petru Tăslăuanu (1880–1957) and Cornel Tăslăuanu (1889–1974) did not experience such a significant social rise, although they were more than just peasants and had successful careers. Petru Tăslăuanu was a teacher and the headmaster of the primary school in Bilbor, while Cornel Tăslăuanu was a craftsman who eventually became the mayor of their native village, Bilbor.

References :

Octavian C. Tăslăuanu, Spovedanii, Ediție îngrijită de George-Bogdan Tofan, prefață de Filip-Lucian Iorga, Editura Mega, 2023.

Cornelia Luminița Radu, Revista Luceafărul, în Revista Română de Istorie a Cărții; Bucharest Iss. 3/4, (2006/2007): 40–46, 304–305, 317–318.

The source for pictures: George-Bogdan Tofan, The “Octavian C. Tăslăuanu” Foundation.

Karl Andreas Fabritius (1826–1881), deputy, historian, pastor, teacher, journalist

The Saxon community in the 19th century Transylvania represents an interesting study case for how the changes operated in the entire Habsburg Monarchy manifested at a local level, especially for a group that was German, was a privileged minority in the region and started losing those privileges with the rise of nationalism. The Saxons were brought to Transylvania by various Hungarian kings during the 12th and 13th centuries when it was part of the Hungarian Kingdom. Despite being a demographic minority, they enjoyed longstanding privileges, including land grants, tax exemptions, and the monarch’s protection, even after Transylvania became autonomous under the Ottoman Empire and later the Habsburg Monarchy. However, the situation changed in the 19th century with the emergence of Austria-Hungary and the social transformations of the time. The privileges held by the Saxon community no longer aligned with the new political values of Hungary, which had direct control over Transylvania after 1867, so they were gradually abolished. In response, the Saxons, along with other ethnic groups in Transylvania, adopted various attitudes, influenced by the heterogeneity of political views within their elite. Examining the lives of key leaders within these political groups could provide valuable insight into the impact of these changes and their consequences for individuals. The case of Karl Fabritius offers intriguing insights in this regard. Although he faced massive backlash on the Saxon political scene for his views, he managed to maintain his political position and seat in the Hungarian Parliament, as well as propel some other aspects of his professional life, in the new political climate, which exemplifies the fate of the collaborationists in newly established regimes.

Karl Andreas Fabritius was born on the 28th of October or the 6th of November 1826 in Sighișoara/Schäßburg/Segesvár/, a locality in Transylvania of 3000 inhabitants. From his father’s side, he came from a family attested with the Latin name Fabritius since the 16th century, which gave numerous priests and civil servants. However, the branch of the family of Karl Fabritius was mainly active in crafts and industry, and “belongs to the more prestigious families of Sighișoara due to diligence and marriage connections.”[1] Both his grandfather and his father were craftsmen, the first a tailor, and the latter a bookbinder. His father, also called Andreas Karl Fabritius (1801–1879), married in 1825 Karoline Elisabeth, n. Schuller, daughter of Michael Schuller, a pastor of the Klosdorf/Miklóstelke/Cloașterf branch. Together they had four children: Ottilia (?–1846), who died as an unmarried mother; Sarolta (?–1879), who married a councilor from Sighișoara from Simonis family; Friedrich, who in 1883 was a district judge; and Karl Andreas (1826–1881).

Karl Fabritius studied at the local gymnasium under the guidance of Mihály Gottlieb Schuller (1802–1882), the director of the school, pastor and local personality. Schuller was the son of the pastor Michael Schuller from Cloașterf, thus being K. Fabritius’s uncle on the mother’s side. The relationship with him seemed to have improved Fabritius school performance. He also had as a teacher Georg Daniel Teutsch (1817–1893), a figure that was going to mark Fabritius’s life in major ways later. For higher education, Fabritius wished to pursue a career in law, but at his grandfather’s insistence and with his financial support, in 1847 Fabritius went abroad to study theology and history in Leipzig, where he was involved in the revolution of 1848. Due to financial problems, Fabritius applied later for support from the Austrian government, as well as from Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, a cultural Saxon association from Transylvania, of which he was a member. Still, this was not enough and in 1849 left for Vienna, where he met ministerial school councilor Johann Karl Schuller (1794–1865), who helped Fabritius in his historical pursuits. Fabritius soon moved to Bratislava as an editor for Pressburger Zeitung, and shortly after he received a position at Siebenbürger Bote, a newspaper in Sibiu/Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben, Transylvania. This was the reason for his return to his homeland in August 1850. However, Fabritius’s ideas were not well received by the owners of the newspaper, and he was fired after a month.

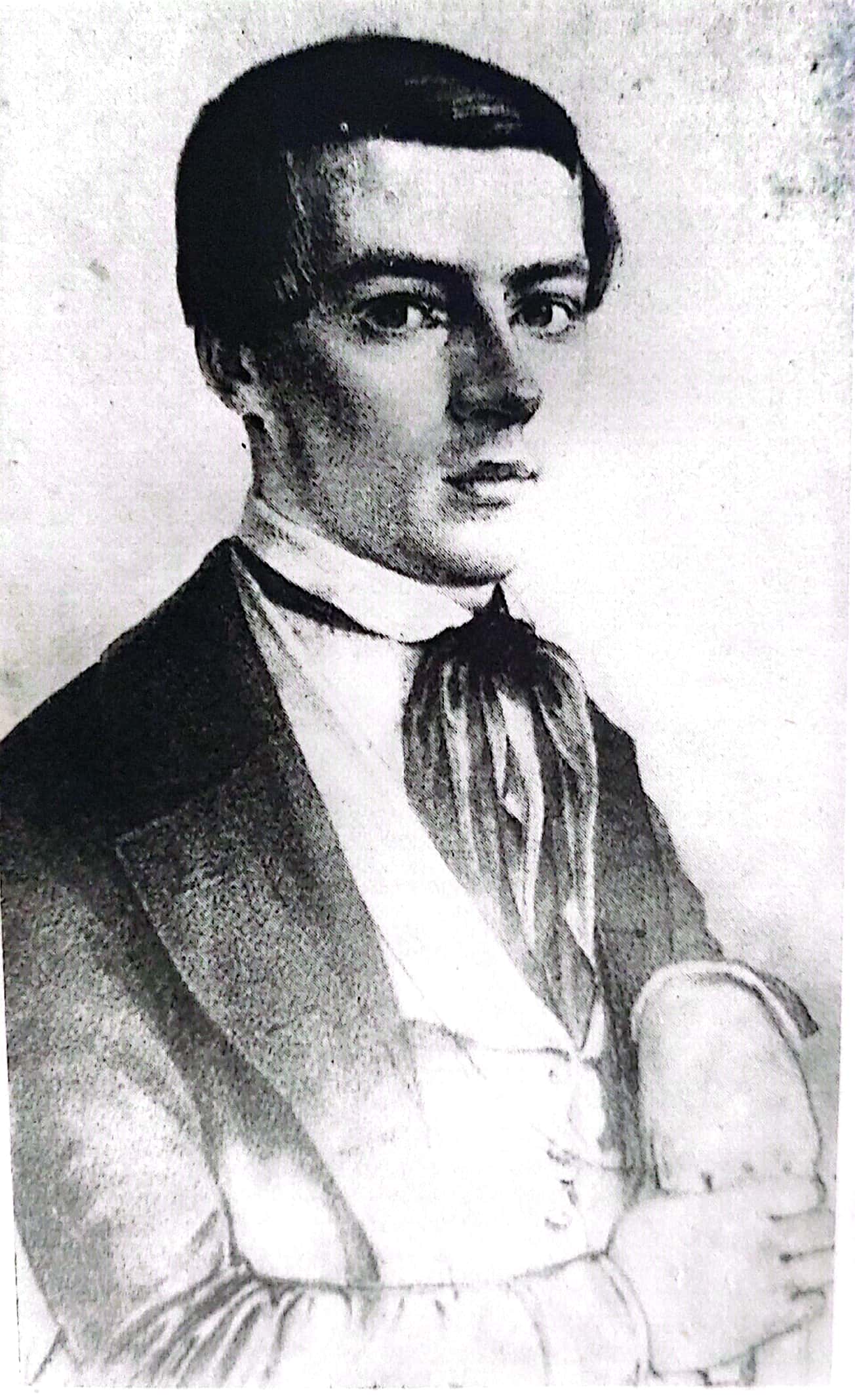

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

In October 1850 Fabritius obtained a position as a teacher at the gymnasium in Sighișoara, where G. D. Teutsch was a director at the time. Together with his former teachers M. Schuller and G. D. Teutsch, Fabritius also got more involved in the activities organized by Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, and through it, he started disseminating his historical research on which he worked since his studies. Due to some conflicts between the school’s director and the local consistory, Fabritius lost his teaching position in 1855, but soon after he was elected as a second town preacher in Sighișoara, a position much better paid than the one of a teacher. His luck changed afterwards. Fabritius applied for a pastor position in Merghindeal/Mergeln/Morgonda and Stejărișu/Probstdorf/Prépostfalva in 1857, then in Apold/Trappold in 1859. However, he did not succeed in any place, possibly because of his friendship with G. D. Teutsch. In 1861 Fabritius was named the first city preacher, but in reality, his salary was lower than before. He applied again for a pastor position in Brădeni/Henndorf/Hégen in 1865, but he was rejected.

K. Fabritius entered the political scene in 1867, at the time of the political compromise between Vienna and Pest that lead to the establishment of Austria-Hungary. He also became the “spiritual leader” of the “Young Saxons,” a political group of Transylvanian Saxons with liberal leanings and which considered collaborating with Pest, as well as with the other ethnic groups. This was in opposition with the political passivity adopted by the “Old Saxons”, the rival political group on the local scene. Between 1867 and 1881 Fabritius was elected five times as a deputy for Sighișoara on the lists of the governmental parties. He also became pastor in Apold in 1868. The sources do not mention any reason why K. Fabritius insisted on this village again, however, a branch of the Fabritius family had a few members that had previously been pastors or were connected to Apold. In 1872 Fabritius became a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Science, which further facilitated his historical research. In 1876, he received the opportunity to be appointed school inspector and even Lord-Lieutenant. Fabritius refused both positions, the reason being that he did not want any personal gain just for being a deputy.

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

However, Fabritius’s liberal and collaborationist political attitude with the Hungarian governmental party produced a rupture in his relationship with G. D. Teutsch, who after 1867 became the leader of the “Old Saxons.” Already at the beginning of his second mandate, Fabritius started receiving personal attacks from the opposition’s press. In 1872 Fabritius mentioned to his family his thoughts of quitting politics, because of the harassment he received, mentioning that he was continuing only to get access to the archives and libraries in Budapest. The attacks did not stop only at the political level. G. D. Teutsch became bishop of the Evangelical Church in Transylvania in 1867, and the president of Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde in 1869. Teutsch criticized Fabritius’s historical writings and prevented their publication by the Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde. Moreover, Teutsch questioned Fabritius on whether he could fulfill his duty in his parish, given his frequent trips to Budapest. The scandal gained proportions around 1875–1876 when Fabritius encountered difficulties in being reelected and received death threats. In 1879, Fabritius quit his position as pastor in Apold. Afterwards, he expressed he wanted to focus just on his historical research and less on politics, given the political losses for the Transylvanian Saxons in the past decade, although Fabritius still had a mandate. However, 1879 is also the last year he published something, his works afterward remaining in manuscript. An accident in the Budapest University Library in December 1880 probably also contributed to this. Fabritius was injured and this led to his death on 2nd February 1881.

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

Very little information has been preserved about Karl Fabritius’s family, despite the long tradition of his family, as well as the number of children he had. Fabritius married in 1852 Friderice, n. Roth (1834–?), the daughter of Fridrich Roth, k. k. district judge in Cristuru Secuiesc/Szeklerkreuz/Székelykeresztúr, and of Amalia, n. Hirling. Karl Fabritius and Friderice had ten children together, of which only six survived to adulthood. Unfortunately, only five of their children could be identified in the parish registers, as not all of them were preserved. However, the ones still existent offer interesting glimpses in Fabritius’s family life. Ludvig Franz (1862–1863), Victorine (1864–1864), and Andreas Oskar (1868–1871) died in early infancy, while two other children survived well into their old age: Guido Robert (1865–1949), and Erich Bernhard (1872–1955). Details in the witnesses’ column for both Karl’s and Friedrice’s wedding, as well as for some of their children’s baptism seem to reveal another family connection. The name of Franz Simonis (1820–1884), another Saxon deputy from Transylvania, appears regularly, alongside that of Adolph Hirling. This makes sense as his sister was married in Simonis’s family, but also that Karl Fabritius might have had a relatively close connection to his mother-in-law’s family, related to that of Simonis through Franz Simonis’s marriage with Caroline Juliane, n. Hirling, in 1849. Also, it cannot be overlooked that one of Fabritius’s brothers, Friedrich, became a district judge, as Fabritius’s father-in-law, although his brother’s location is unknown.

More information about Guido Robert, one of Karl Fabritius’s sons, is revealed in one of his grandchildren’s biographies, namely of Guido Fabritius (1907–after 1989). Guido Robert left his hometown and moved to Sibiu, where he became the owner of the old Bären pharmacy. He married Melitta, n. Gunesch, daughter of pastor Gustav Hugo Gunesch, and together, they had seven children. Guido Fabritius was their only son and followed his father’s footsteps. He studied pharmacy in Cluj-Napoca/Klausenburg/Kolozsvár in 1932, then at the University of Berlin. He returned and worked at his father’s pharmacy, then took it over in his own name in 1936. He also co-founded the Deutschen Apothekerverband von Rumänien. During the war, he was part of the Wehrmacht (the Nazi unified armies). After the war, he lived in different cities in Western Germany, where he worked as a pharmacist, while he researched the Transylvanian pharmaceutical history, as well as his own family history, thus having a similar predilection for history as his grandfather. Regarding his familial life, Guido Robert married twice: in 1938 with Anne Schaffarczik, a secondary school teacher, with whom he had a daughter that died in early adulthood, and in 1952 with Luise Bleckmann-Körner, with whom he had a daughter and a son.

Selected bibliography:

Daubner, Hans D. “130 Jahre seit dem Tod von Carl Fabritius – eine Schäßurger Personlichkeit,” Schäßurger Nachrichten, no. 35 (June 2011): 24–25.

Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

Kozma, Ferenc. Emlékebeszed Fabritius Károly Levelező Tag Fölött, Budapest: M. T. Akadémia Könyvkaido-Hivatala, 1883.

Kwan, Jonathan. “Transylvanian Saxon Politics and Imperial Germany, 1871–1876,” The Historical Journal 61, no. 4 (2018): 991–1015.

Kwan, Jonathan. “Transylvanian Saxon Politics, Hungarian State Building and the Case of the Allgemeiner Deutscher Schulverein (1881–82),” The English Historical Review 127, no. 526 (2012): 592–624.

[1] Ferenc Kozma, Emlékebeszed Fabritius Károly Levelező Tag Fölött, (Budapest: M. T. Akadémia Könyvkaido-Hivatala, 1883), 4.

Friedrich Janka (1878–1957)

Friedrich Janka was born on 28 October 1878 in Chomutov (Komotau), a German-speaking town in Northern Bohemia. His father was Karl Emanuel Janka (1839–1917), a District Commissioner, and his mother Franziska Wieshofer (1839–1915), a brewer’s daughter. Friedrich spent most of his childhood and youth in Prague, where his father worked at the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Karl came from a rural environment – his father was a farmer and his mother’s family were farmers as well. However, he studied law at university and started a career in the state administration. He became a Senior Governor’s Office Official, District Captain and finally Junior Governor’s Office Councillor. Before his retirement in 1904 he was promoted to a Senior Councillor. He died in Prague on 7 July 1917.

In 1903 Friedrich received a degree in law at German Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. Shortly afterwards, he began to work at the Bohemian Governor’s Office as a trainee official. At that time his father Karl was still employed in this institution as a Junior Councillor. Karl retired soon after his son got this job. It is very likely that Friedrich’s path to the Governor’s Office was much smoother than his father’s and that Friedrich’s position was secured by his family connections. In 1905 Friedrich was promoted to a junior official and transferred to Liberec (Reichenberg), a large German-speaking town in Northern Bohemia. After two years he returned to Prague and continued his career at the Governor’s Office. In 1908 he became a District Commissioner and in 1911 a Senior Official. In the same year he married Božena Anna Mayer (* 1880), daughter of a brewer Josef Mayer (1846–1902).

At that time Czechs and Germans held long negotiations about their position within the Habsburg Empire. There were several topics which were discussed during these negotiations – the use of language at state offices, processing and translating documents, determining which districts will be monolingual and which bilingual, administrative reforms and changes in the election rules and finally, schools for ethnic minorities. Friedrich Janka played an important part in these talks. He was responsible for German meeting proceedings and communication between the Governor’s Office in Prague and the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna. The Bohemian Governor Franz Thun (1847–1899) trusted Friedrich with confidential information and relied on him. Although the negotiations as a whole did not succeed, Friedrich proved his abilities and was promoted.

Franz von Thun und Hohenstein (1847–1916) od Siegmunda l'Allemand (1840–1910).

However, in October 1918, when the Czechoslovak Republic was established, Friedrich was forced to leave his current position, because of his German origin and loyalty to the previous regime. Since he could not retire yet, he got a job as a translator of important legal documents, including the Czechoslovak Constitution. In the late 1930s, the political situation in Central Europe was about to change immensely again. In September 1938 the Munich Pact was signed and Czechoslovakia ceded large territories to Germany. On 27 October Friedrich celebrated his 60th birthday and was entitled to pension, so a month later he wrote a request for retirement. By the end of the year, it was approved.

A few months later, the German army invaded what was left of former Bohemian lands and the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia was established. A massive Germanisation of all social spheres followed. Friedrich probably saw this as an opportunity and decided to acknowledge his German background. In a questionnaire for the determination of German nationality from July 1939 Friedrich and his family confirmed that they were German citizens, members of NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party) and several German clubs. Friedrich also requested reinstatement in the political administration and became a Governmental Commissioner. After his return to the active service, Friedrich complained about losing his position in 1918 and asked for compensation, which he was given. He worked for almost three years and applied for pension again. In 1944 he retired for the second time. Thanks to these three years in public service, his pension increased significantly – from 49,800 crowns to 80,160 crowns per year.

Map of Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from a German pocket atlas, 1939–1940.

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia 20 korun (1944) banknotes were issued during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.

Friedrich had only one son – Friedrich Karl Josef (later called Fritz), who was born on 16 November 1913 in Prague. Fritzʼs career flourished in the Protectorate as well. In 1939 he worked as a lawyer for Ast Prag – German military-intelligence service in Prague. He was a member of several German clubs, the same NSDAP group as his father and a candidate for SA – the paramilitary wing of the party. In 1942 he was recruited into the German army, but it is not clear whether he survived the war or not.

When the war ended, Friedrich was once again on the wrong side. In May 1945 he lost his pension and a few months later he was investigated for breaking the presidential decree no. 16 from 19 June 1945. According to this law, as a member of NSDAP he was supposed to be sentenced to five to twenty-five years’ imprisonment. The questionnaire for determination of German nationality was used as evidence in Janka’s personal file. It is not clear if he was actually condemned or not. It is more likely that he was expelled from Czechoslovakia like other German citizens.

The story of three generations of Bohemian Germans from the Janka family reflects the realities of life in four different regimes, which changed within a relatively short period of time. Karl was born into a family of farmers and it was university education which helped him to improve his social status. As a civil servant he was able to support his son Friedrich’s career at the Governor’s Office. Friedrich used this opportunity but lost his position after the Czechoslovak Republic was created. During the Protectorate period he shortly regained his former status but as a member of NSDAP he could not stay in Czechoslovakia after the end of war.

Literature and sources:

Eva Drašarová, “Die Rolle der Konzeptsbeamten bei der politischen Lösung der nationalen Beziehungen in Böhmen. Das Beispiel von Statthaltereisekretär Friedrich Janka,” in Führer, Akteure hinter den Kulissen oder tatenlos zuschauende? Der deutsch-tschechische Ausgleich an der Wende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert aus der Perspektive der Vertreter der Staats- und Selbstverwaltung edited by Martin Klečacký and Martin Klement (edd.).

Martin Klečacký, Převzetí moci. Státní správa v počátcích Československé republiky 1918–1920 na příkladu Čech. Český Časopis historický 116, 2018, 693–732

Martin Klečacký et al., Slovník představitelů politické správy v Čechách v letech 1849–1918 (Praha: Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR, v.v.i., Národní archiv, 2020).

Luboš Velek, “Projekt česko-německého národnostního vyrovnání v Čechách v letech 1890–1915 a jeho geneze”, in Promarněná šance. Edice dokumentů k česko-německému vyrovnání před první světovou válkou. Korespondence a protokoly 1911–1912, I, eds. Eva Drašarová, Roman Horký, Jiří Šouša and Luboš Velek: (Praha: Národní archiv, 2008).

Die Verfassung der Tschechoslowakischen Republik. Prag 1922–1923 (two volumes).

Dekret č. 16/1945 Sb, § 3. Dekret presidenta republiky o potrestání nacistických zločinců, zrádců a jejich pomahačů a o mimořádných lidových soudech. Accessible at https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1945-16.

National Archives, fonds Prezidium zemského úřadu (PZÚ) – personal files, box 25, personal file – Bedřich Janka.

State Regional Archives in Litoměřice, Collection of registers, call number 2615, sign. 62/21, 363.

State Regional Archives Plzeň, Collection of registers of the West Bohemian Region, Plasy 16, 14.

Preissová-Kaizlová née Píšová, Kamila (20. 7. 1871 – 4. 4. 1930), wife of a deputy and Minister of Finance

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

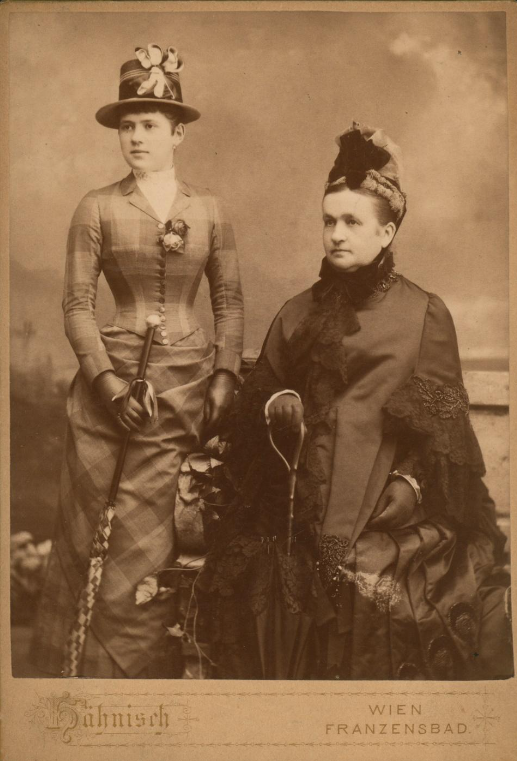

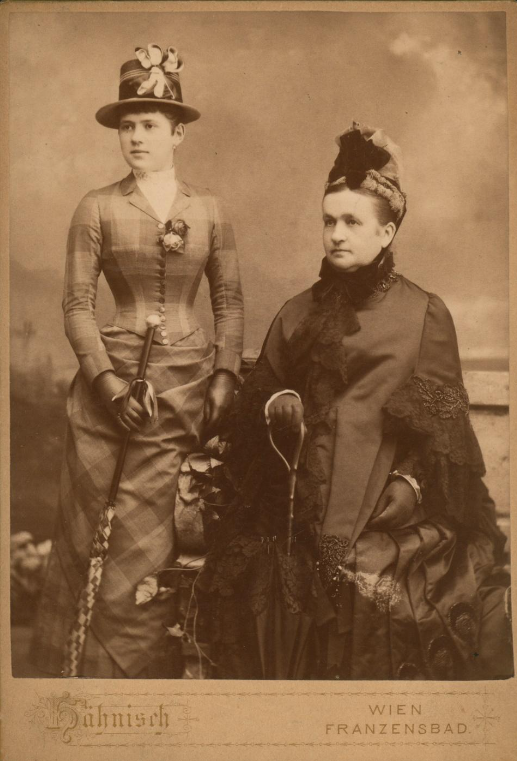

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.