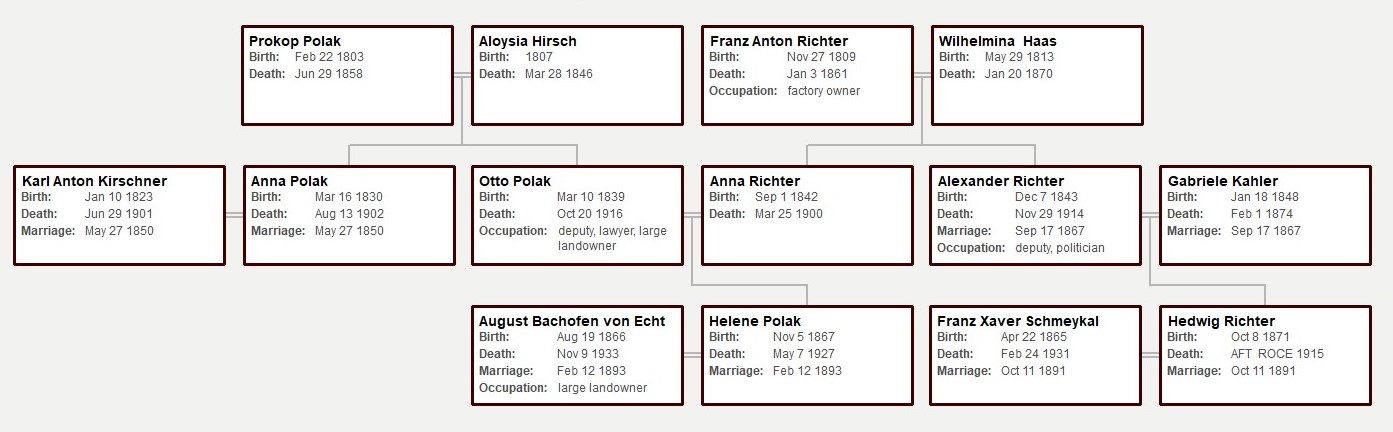

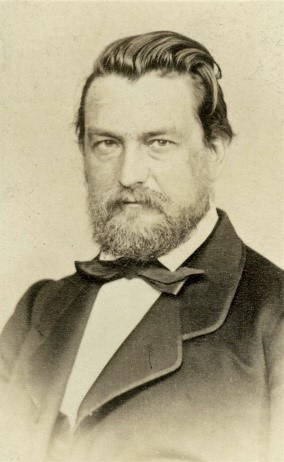

Iosif Gall (1839–1912) – judge, deputy, philanthropist

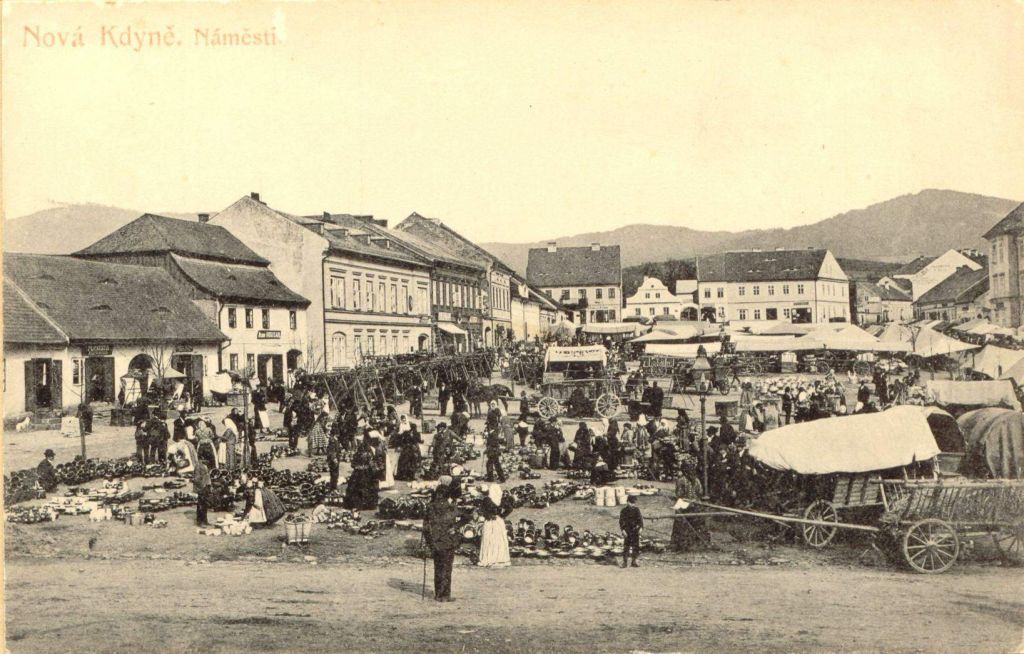

Iosif Gall (Bistrița-Năsăud County Branch of the Romanian State Archives)

On Christmas Eve in 1870, the Metropolitan Bishop of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania, Andrei Șaguna (1809–1876), wrote to a close friend about the marriage of one of the most valuable jurists of Dualist Hungary of that time, Dr. Iosif Gall:

"What do you know of Gall and his companionship or marriage? I have written to him that Dunca will give his daughter away now with [a dowry of] 12,000 fl. alongside anything that will be left after his death, to be divided into three parts, among his three daughters; and he will not answer me; and Dunca grows impatient, for he wants to know, will anything come of it or nothing? Some people are maddened by good fortune; I fear lest this fate has befallen Gall also."

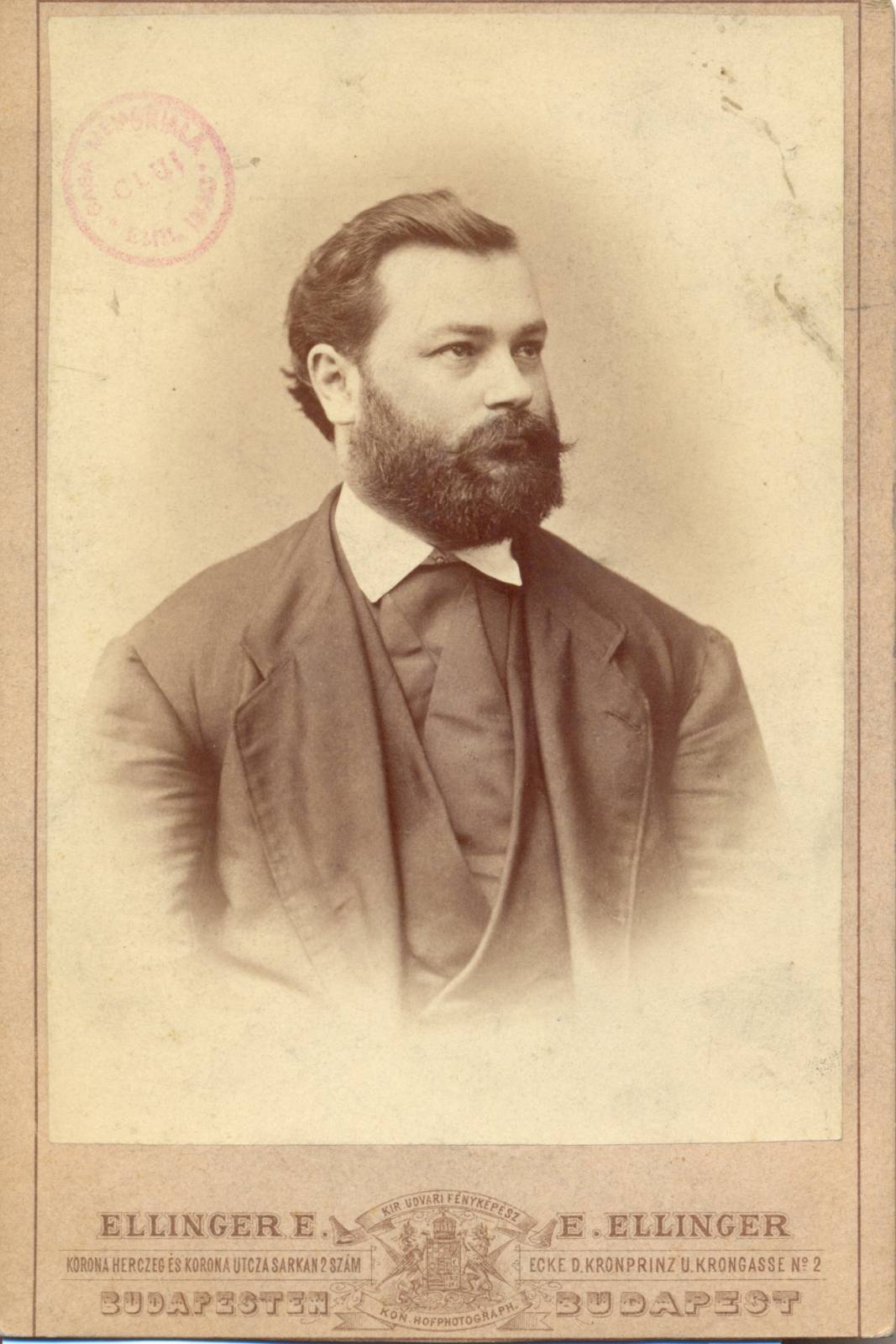

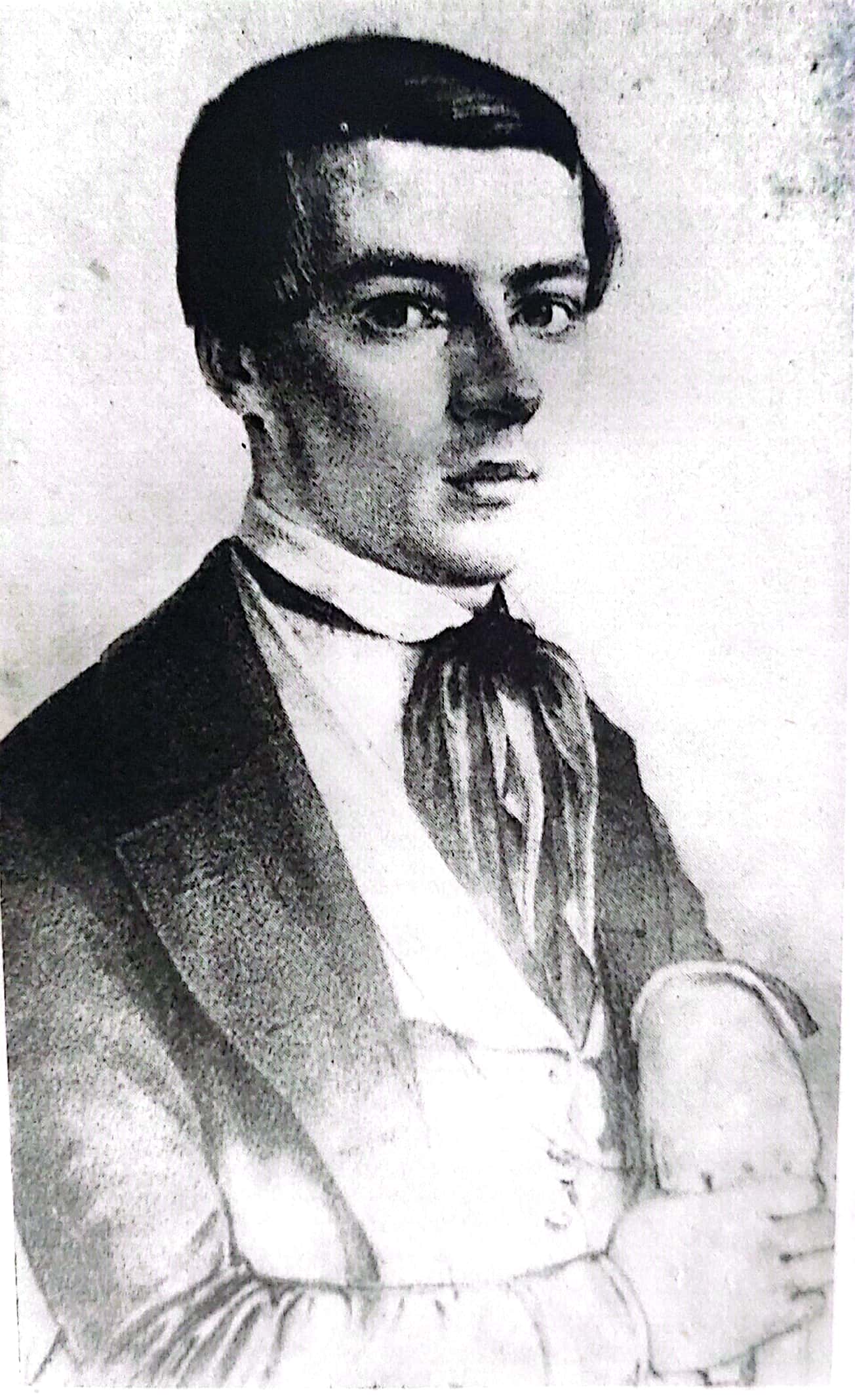

Iosif Gall (“Octavian Goga” Cluj County Library)

The Romanian high clergyman, an emblematic figure of the national movement in Transylvania, whose influence even reached the circles of the Viennese Court, was concerned with Iosif Gall's fate ever since the latter had been orphaned at the age of 12. Iosif's father, the Orthodox archpriest Grigore Gall (?–1851), had died in 1851, leaving his wife, Carolina (née Stan de Borosjenő) (1814–1904), a widow with four children.

With the support of Andrei, Baron of Șaguna, Iosif Gall had managed to attend secondary school in Cluj (Hu. Kolozsvár) and obtain a higher education at the Academy of Law in Sibiu (hu. Nagyszeben) and the University of Vienna. The metropolitan bishop's support – especially financial support, but not limited to material issues – was fully rewarded by the young Iosif Gall in 1860, when the student was awarded a doctorate in law at the university in the imperial capital.

After finishing his studies, Iosif Gall began his professional career, which progressed at a fast pace, in line with his legal skills and knowledge. In Vienna, for a year after obtaining his doctorate, he completed a compulsory legal traineeship to qualify as a lawyer. Immediately after the end of this period he was appointed as a trainee at the Transylvanian Court of Vienna. Due to his admirable activity, he was shortly afterwards promoted to a superior office within the same institution. In 1867, with the administrative changes brought by the Ausgleich, Iosif Gall was transferred to the Royal Hungarian Ministry of Justice. A year later, in 1868, he was transferred again to the Transylvanian supreme court, and with its dissolution to one of the higher courts in Budapest (Hu. Hétszemélyes Tábla), where he was assigned to the Transylvanian division. After only one year he was appointed report on the proceedings at the Court of Cassation, and in 1870, when he was only 32 years old, he became a judge at the King’s Bench in Budapest. Shortly afterwards he returned to the Court of Cassation as a counselor.

This period of his life, which was marked by outstanding achievements, also witnessed Andrei Șaguna’s efforts to see him settled from a personal perspective as well as a professional one. In 1871 Gall became engaged to Paulina Dunca, daughter of Paul Dunca (1800–1888) from Sibiu, a former government councilor and MP. The marriage between the two, however, never took place because of disputes between Iosif Gall and Paul Dunca, most probably concerning the young girl's dowry.

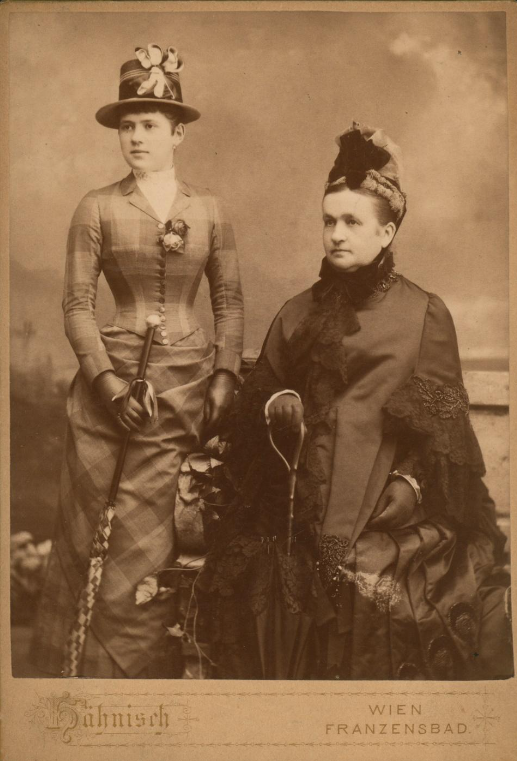

Eventually, eight years later, his professional fulfillment was matched by a personal one through his marriage to Ecaterina of Agora (?–1899), a widow who owned important possessions in Banat and Croatia. She had previously been wed to Ioan Dobran, from whom she had inherited an important estate. Ecaterina Gall de Agora came from an old family of Aromanian origin settled in Banat. She was also the owner of a large estate at Lucareț (Hu. Lukarec). In Budapest she enjoyed wide popularity and was considered one of the capital's greatest philanthropists thanks to the balls organized to support the Romanian students at the local university. Seen from the perspective of his wife's social status, Gall's marriage, but especially the break-up of the engagement with Paulina Dunca, shows that the young Romanian jurist had thought out his marriage strategy with the utmost pragmatism.

In fact, the results of this social ascent, which complemented his professional one, leveled the way for his career to divert towards politics. In 1881, Iosif Gall resigned from his post as an adviser to the Court of Cassation and gave up his pension, convinced that he could better serve his nation if he were to work in the political arena. On his retirement from the civil service, he was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown Class III and later the Order of Franz Joseph in the rank of Grand Officer.

In the same year he filed his candidacy for the parliamentary deputy of the Recaș (Hu. Rékas) constituency, Temes county, as a supporter of the government program. After winning the elections, he represented this electoral constituency throughout the whole parliamentary cycle 1881–1884. During this period, he was a member of the Parliament's Justice Committee and its rapporteur. In the elections of 1884, he stood again and managed to win another mandate as a Member of Parliament. The 1884–1887 parliamentary cycle was the last of his career in the Lower House of the Hungarian Parliament, as in May 1887 he was appointed lifetime member of the House of Magnates, the Upper House of the Budapest Parliament. He served in this capacity until the end of his life.

Iosif Gall’s as a magnate (Ovidiu Emil Iudean’s personal archive)

One of the most important political endeavors of Iosif Gall's career was the founding of the Romanian Moderate Party, together with the Orthodox Metropolitan bishop Miron Romanul (1828–1898). The organization of the Moderate conference in Budapest in March 1884 and his financial support for the Viitorul [The Future] gazette, the press organ of the newly founded party, are just two of the reasons for his full involvement in this political project. Despite the failure of the moderates, Gall remained convinced of the need for the Romanian nation in Hungary to adopt a moderate course of cooperation with the Hungarian government to achieve social, cultural and ecclesiastical development.

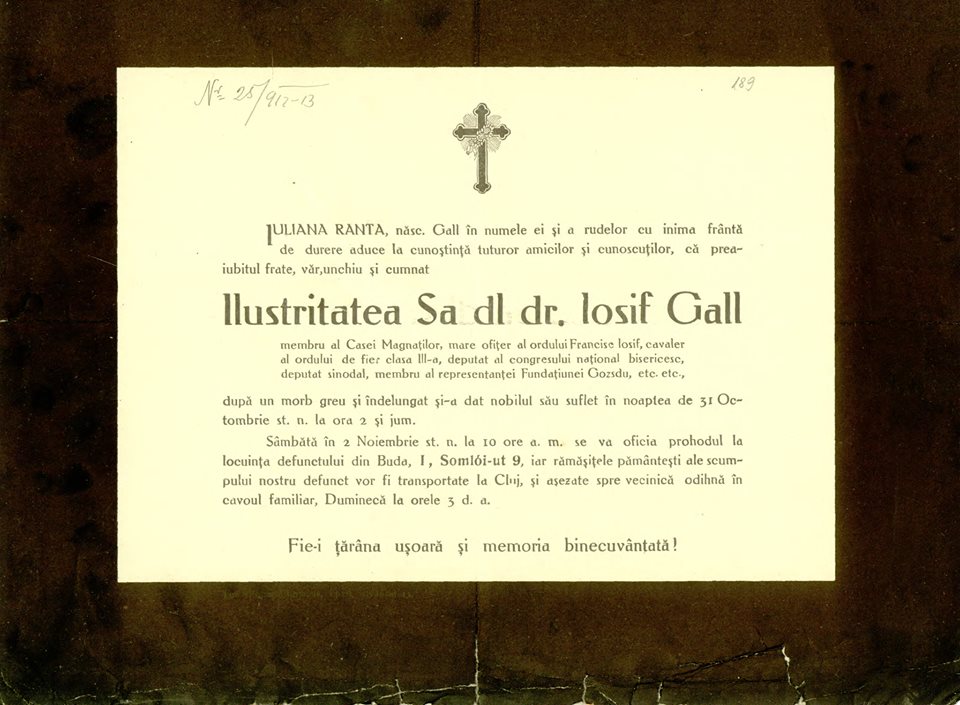

Iosif Gall died in Budapest on the night of October 17/30 to 18/31, 1912. He was buried in Cluj on October 21/November 3 in the presence of his family and a large public. As he had no direct heirs, in his will he left a large part of his estate, about 600,000 crowns, to set up two foundations, both under the name "Agora-Gall", for cultural and philanthropic purposes. Each of the two was to be administered separately, one by the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania and the other by the Serbian Orthodox Church, residing in Karlovci.

Iosif Gall’s obiturary (Bistrița-Năsăud County Branch of the Romanian State Archives)

Iosif Gall’s grave (Ovidiu Emil Iudean’s personal archive)

Owing to this last grand gesture, as well as all his legal, social-cultural and political activity, his biographer, T. V. Păcățian (1852–1941), rightfully called him "The Lucareț Maecena".

Bibliography:

Păcăţian Teodor V., Iudean Ovidiu Emil, Un mecenat român – dr. Iosif Gall (Cluj-Napoca : Presa Universitară Clujeană, 2012)

Iudean Ovidiu Emil, The Romanian governmental representatives in the Budapest Parliament (1881–1918). Cluj-Napoca : Mega, 2016

Berényi Maria, Personalităţi marcante în istoria şi cultura românilor din Ungaria (secolul XIX) (Giula: Institutul de Cercetări al Românilor din Ungaria, 2013)

Ioan Cavaler de Pușcariu (1824–1912)

Image source: https://ro.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ioan_Pușcariu#/media/Fișier:Ioan_Pușcariu.jpg

One of the leading Romanians of the 19th century in Transylvania, Visarion Roman (1833–1885), wrote at one point, with annoyance, to one of his friends: “Perhaps we, this kind of people, are destined to be everything” (Netea, Noi contribuții, p. 34–35). His dissatisfaction was due to the fact that, in the mid-19th century, there were so few Romanians in Transylvania whose training would allowed them to hold public office or lead the institutions of civil society that multipositionality was ubiquitous and forced them into an often undesirably high pace and amount of work.

One of these people who was “destined to be everything” was Ioan Ritter von Pușcariu (1824–1912).

The Pușcașu family settled in the village of Sohodolul Branului, in Southern Transylvania in the early 1700s, and in the second half of the century its members were already mentioned as priests and merchants, as well as writers of petitions to the authorities, which underlines an elite status within the community. From this line of priests, some of whom one can still see today immortalized in the painted porch of the churches they built, was born in 1824 Ioan, the first of the ten children of the priest Ioan (1878–1871) and of his wife Stana (1801–1886), and also the first of those who would change the name of Pușcașu to Pușcariu.

Ioan Pușcariu attended primary school in Sohodolul Branului and then in the city of Brașov / Kronstadt / Brassó, where he also attended the local Catholic secondary school. He graduated in 1842 at the Catholic gymnasium in Sibiu / Hermannstadt / Nagyszeben, after which he attended an Orthodox theological course of six months. However, the following year he changed his mind and began studying Law at the Academic Lyceum of the Piarists in Cluj / Kolozsvár, then in 1846 at the Academy of Law in Sibiu. The family's priestly tradition was continued by his brother Ilarion (Bucur) Pușcariu (1842–1922).

In the spring of 1848, freshly graduated from legal studies, Ioan Pușcariu got actively involved in the revolutionary events, as steward of the national assembly of Romanians in Blaj / Balázsfalva, military tribune, and later revolutionary propaganda commissioner in Walachia. During the Neo-Absolutist period, like many Romanian graduates of legal studies, he pursued a career as a civil servant in the administrative apparatus of the province, most probably on the recommendation and with the support of the Orthodox bishop Andrei Șaguna (1809–1873), whose ecclesiastical, cultural and political initiatives he would constantly support throughout his life. After changing several minor offices in Hunyad/Hunedoara County, he became in 1854 sheriff (szolgabíró/pretor) of sub-district Scharken/Sárkány /Șercaia, in Făgăraș. Concurrently, he published books of legal commentaries and legal popularization in Romanian, and a dictionary of bureaucratic terms in Romanian and German.

After 1860, amidst the political changes brought about by the liberal regime, the former local civil servant became in 1861 drafter at the Royal Chancellery of Transylvania in Vienna, another position to which Șaguna’s recommendation contributed greatly. In January 1862, amidst the Viennese government’s attempts to reduce the political opposition of the Hungarians in Transylvania, Ioan Pușcariu was appointed to an important position in the provincial administration: county-commissioner (alispán) of Kükülő/Târnava (Cetatea de Baltă) County, a position he held until August 1865. During these four years he was also elected deputy to the provincial diet in Sibiu (1863–1864), deputy to the Imperial Council (1864–1865), and deputy to the provincial Diet in Cluj (1865). His upstanding career was crowned by his ennoblement by imperial decree on 10 July 1864 with the Order of the Iron Crown third class, and the rank of knight (Ritter von).

The esteem he enjoyed among the authorities and the support of Bishop Șaguna were manifested even when the political regime began to change and the diet of Sibiu was dissolved by imperial decree. Pușcariu was among the few Romanians who did not lose their offices, instead he was only relocated from Kükülő County to the position of Captain General of the Fogaras/Făgăraș District (August 1865). It is illustrative of the expectations that the administrative leader of a county had to fulfil at the time the words of Count György Haller (1818–1892), who explained to Pușcariu in 1865 that he had refused to take up the leading office of Kükülő County because he would not be able to satisfy “a couple of hundred hungry aspirants for 20 years (i.e., since 1849). It would have been woe to me if I could not have given them all bread” (Pușcariu, Notițe..., 1913, p. 84).

In 1866 Ioan Pușcariu was elected deputy to the Hungarian Parliament in one of the constituencies of the Fogaras/Făgăraș District, and until 1869 he was among the so called “activists” – those Romanian political leaders who tried to obtain as many political concessions as possible from the Hungarian political elite, and at the same time to motivate both the rest of the Romanian elite and the voters to continue their involvement in political life. His position as a mediator was also recognised and rewarded by the Hungarian government when he was appointed as a section councillor in the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Instruction in December 1867. By 1869, however, his star was already fading. After three years of successive political failures from the part of the “actvists”, the newly founded Romanian National Party of Transylvania (March 1869) decided to adopt the policy of electoral passivity, thereby refusing to recognise the legal effects of the Settlement of 1867. Ioan Ritter von Pușcariu was among the four participants in the party’s conference (from ca. 400) who voted against passivity and stood by his position in the years that followed. Indeed, the fact that he had been appointed in May 1869 as a judge of the highest court in Hungary, the Royal Curia, must have contributed considerably to him maintaining his political option both in the 1870s and in the 1880s, until his retirement as a judge in 1890.

At the same time, he remained close to the circles of the Orthodox Metropolitan See of Sibiu, where his brother Ilarion became an archimandrite. In 1884 he was one of the supporters of the newly-founded, short-lived Romanian Moderate Party, which promoted collaboration with Hungarian governments, but ultimately failed to secure the support of the Romanian voters. This was the last important moment of his political career, after which, as an old man, he only concerned himself with his judicial office and with scholarly activities.

As early as 1861, Ion Pușcariu was one of the initiators of the Romanian cultural association in Transylvania: Astra. He remained a member all his life, but from 1873 he also held leading positions in the Society for the Romanian Theatre Fund until 1889. He was also among the promoters of the national costume among the Romanian elite. Finally, he was one of the leading members of the Gojdu Foundation, which supported the studies of numerous Romanian Orthodox pupils and students in Hungary. In 1877 Ioan Pușcariu was elected honorary member of the Romanian Academy in Bucharest, to whose work he contributed historical, genealogical, and philological writings. He excelled less in the field of literary creation, where his poetic attempts, although consistent, never rose to a quality that would ensure his recognition. On the other hand, he carried on a constant scholarly activity as a member of Astra until the last years of his life: “Even in his old age, the much-missed deceased, at whose coffin we lie, did not hesitate for many years to take part in the work of our historical section, often enriching it and giving it wise advice” (Necrologuri, p. 153).

The life and career of Ioan Pușcariu illustrates the opportunities for social mobility among the Romanians in Transylvania offered by education and the favourable context of the 1850s and 1860s, but also the important role played by the church in the formation of the national political elite. An important number of Romanian politicians and civil servants came from clerical families in the early and mid-nineteenth century, and for those who reached important positions in the provincial apparatus or sometimes even in the capital city of the Monarchy, the support of churches of both denominations (in the case of Pușcariu the Orthodox one) was always a mandatory requirement.

Bibliography

Necrologuri, in Transilvania 43, 1912, nr. 1–2, p. 152–154.

Keith Hitchins, A Nation Affirmed: The Romanian National Movement in Transylvania, 1860–1914, Bucharest, 1999.

Nicolae Josan, Ioan Pușcariu (1824–1912). Viața și activitatea, Alba Iulia, 1997.

Ioan cavaler de Pușcariu, Notițe despre întâmplările contemporane, Sibiu, 1913.

Ioan cavaler de Pușcariu, Notițe despre întâmplările contemporane. Partea a II-a. Despre pasivitatea politică a românilor și urmările ei, ediție îngrijită de N. Josan, București, 2004.

Sextil Pușcariu, Spița unui neam din Ardeal, ediție, note și glosar de Magdalena Vulpe, Cluj, 1998.

Count Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly, graphic from the portrait collection of the Austrian National Library

Count Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly, graphic from the portrait collection of the Austrian National Library

The life of Alexander Mensdorff-Pouilly was fundamentally different from that of other officials. He came from an old aristocratic family, the Pouilly, which left their homeland during the French Revolution. Thus, Alexander’s father Emanuel (1777–1852) had to build a position for himself in a completely different environment. He opted for a military career in the service of the Austrian Emperor and, like his brother, decided to take the name Mensdorff, which was supposed to help him to better adapt in the German-speaking world. His marriage to Princess Sophie of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1778–1835), who was of a substantially higher status, undoubtedly also helped him consolidate his position. Thanks to this marriage, Emmanuel and his descendants became related to a number of European noble families. Perhaps the most famous among his male cousins was Albert (1819–1861), husband of Queen Victoria of Britain (1819–1901), while the most famous female cousin was Queen Victoria herself. The loving union of Emmanuel and Sophie produced five sons, four of whom survived to adulthood – Hugo (1806–1847), Alphonse (1810–1894), Alexander (1813–1871) and Arthur (1817–1904). Their life trajectories show how varied the fates of 19th-century nobility could be.

Coat of arms of the family Mensdorff Pouilly

Coat of arms of the family Mensdorff Pouilly

The eldest of the brothers, Hugo, was born in Coburg on August 24, 1806. Coburg was also the city where he grew up and received a private education. Emanuel wished to make military officers of his sons, and he succeeded. Hugo joined the army and became a cavalry officer. Although he was the eldest son and it was primarily him who was expected to ensure the continuation of the family, Hugo never married. He was no stranger to the company of women, but he did not meet a suitable partner from the upper classes. He preferred to remain alone rather than live in an unhappy marriage. During his military career, he won numerous awards and reached the rank of colonel. In 1847, however, his health began to fail. He was treated at a spa, first in Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad) and then in Jeseník (Freiwaldau), where he succumbed to laryngitis at the age of only 41.

The second-born Alphonse was born on 25 January 1810 in Coburg. His father intended a naval career for him. However, Alfonse refused and became an officer in the cavalry, where he attained the rank of colonel. A crucial issue for a man of his position was the choice of a bride. Alphonse seems to have had a lucky hand, since the woman he chose, Therese Dietrichstein (1823–1856), not only came from a good family, but there was also a mutual liking between them. The bride’s father, Franz Xaver of Dietrichstein (1774–1850), was initially not very enthusiastic about the match, hoping for a husband of a higher social position for his daughter. In the end, however, he agreed to their union. After Therese Dietrichstein became the heiress of the Moravian estate of Boskovice (Boskowitz), Alfons abandoned his military career and threw himself into the administration of the estate. For several years, during which they had four children, Alfonse and Therese lived a happy family life in Boskovice In 1856, however, tragedy struck the family – Therese died of scarlet fever. Alfonse resisted remarriage for several years, but the death of his only male heir, Arthur, in 1862, made him reconsider this decision.

His second wife was Marie, Countess of Lamberg (1833–1876), with whom he also had four children. Unfortunately, the second marriage did not last very long either, since Marie died at the age of only 42. But Alfons finally lived to see his longed-for heirs. The elder of them, Alfons Vladimír (1864–1935), later took over Boskovice. Besides taking care of the estate, Adolf also devoted himself to politics. From 1861 he sat in the Moravian Provincial Assembly in Brno and in the following year he also became a life member of the upper chamber of the Austrian Imperial Council. However, he did not see much sense in the exercise of these functions and seems to have been more comfortable with activities at a local level – in 1864–1876 he was mayor of Boskovice and in 1888 he even became its honorary citizen. Alfons died in Boskovice at the ripe age of 84 and was buried in the family tomb in Nečtiny (Preitenstein), which he had built himself.

Alexander was born on August 4, 1813 in Coburg as the third among his siblings. Like his brothers, he grew up in Coburg, where he befriended members of the most prominent European families. From a young age, however, he also felt a sense of belonging to the Austrian state and decided to serve in its army. His military career began in 1829 when he became a cadet in an infantry regiment. Over the next 20 years he rose to the rank of major general. He then entered the diplomatic service and became Austrian ambassador in St. Petersburg. However, he lasted only a year in this position and then returned to the army. At the end of the 1850s it started to become clear that if he really wanted to live up to his family duties, military service alone would not be sufficient. So he began to look around for a suitable bride. According to family correspondence, members of the Mensdorff-Pouilly family considered the mutual affection of both fiancés a necessary condition for marriage. However, Alexander seems to have given up on this requirement.

In 1857 he married Alexandrina of Dietrichstein (1824–1906), the future heiress of the large Mikulov (Nikolsburg) estate in South Moravia. The husband and wife had to find their way to each other, which was difficult at first, as they did not live together. Eventually, however, they became close and their marriage was happy. Four children were born into it, three of whom lived to adulthood – Marie (1858–1889), wife of Count Hugo Kálnoky (1844–1928), Hugo (1858–1920), heir to the estate and husband of the Russian noblewoman Olga Dolgorukova (1873–1946), and Klotylda (1867–1943), wife of Albert Apponyi (1846–1933).

In 1859 Alexander became lieutenant field marshal and two years later Governor in Lvov, where he also served as Commanding General for Galicia and Bukovina. One of the highlights of Alexander’s career was undoubtedly the year 1864, when he was appointed Austrian Foreign Minister. During his tenure, however, Austria lost the Austro-Prussian War, and Alexander was subsequently relieved from his post. At the end of his life, he served as Czech governor in Prague. It was also in Prague that he died on 14 February 1871 and was buried in the family tomb in Mikulov.

The castle in Mikulov today

The castle in Mikulov today

The youngest Arthur, like his brothers, was born in Coburg, on 19 August 1817. He too became an officer in the army and for many years served the Austrian Emperor. However, when it became clear that he would get no further than the rank of major, he decided to leave active service in 1852. Instead, he turned to business. He tried his luck in coal mining but failed. Unfortunately, the income from his lands did not cover his expenses, so he was forced to borrow frequently from his family, including Queen Victoria. Neither was he very successful in his personal life. In 1853 he married Magdalena Kremz (1835–1899), a low-born circus rider, whom he had fallen in love with. His brothers and other relatives strongly criticized him for this decision and never fully accepted Magdalena in their midst. However, they did not reject Arthur himself and continued to help him. Arthur later came to regret his choice, since Magdalena really was not a good match for him, and in 1882 they divorced. Near the end of his life, Arthur found himself a matching bride – Countess Bianca Adamovich de Csepin (1837–1912). After two years of marriage, Arthur died in Velenje, a town in what is now Slovenia.

Service in the army played an absolutely fundamental role in the lives of the four Mensdorff-Pouilly brothers. Along with their aristocratic origin, it enabled them to establish themselves socially and economically in Austrian society. The family’s marriage policy also helped them on their way to the top. It was thanks to his wife’s inheritance that Alphonse became a landowner. As for Alexander, although he himself did not participate in the running of the Mikulov estate, the profits from it allowed even him to lead an expensive life. His clerical career was rather a side effect of the military one, and his social status, abilities and character, which made him popular among the people, undoubtedly played a role in it.

Bibliography:

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Rodinné strategie šlechty. Mensdorffové-Pouilly v 19. století. Praha: Argo, 2007.

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Rod Mensdorff-Pouilly a boskovický velkostatek. In: Ott, Matěj, Markéta Malachová, and Roman Malach: Boskovice 1222–2022. Boskovice: město Boskovice ve spolupráci s Muzeem regionu Boskovicka, 2022.

Švaříčková-Slabáková, Radmila: Šlechtic – Příklad Huga Mensdorffa-Pouilly. In: Fasora, Lukáš, Jiří Hanuš, and Jiří Malíř. Člověk na Moravě 19. století. Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury, 2008.

Brichtová, Dobromila: Zámek Mikulov. Mikulov: Regionální muzeum v Mikulově, 2015.

Brichtová, Dobromila: Pod tvými ochrannými křídly. Od loretánského kostela k hrobce Dietrichsteinů v Mikulově. Mikulov: Turistické informační centrum, 2014.

Steiner, Petr: Hrabě Hugo Kálnoky de Köröspatak (1844–1928). Život a osudy šlechtice na konci 19. století. Časopis Matice moravské 141/1, 2022.

Leon Scridon sr. (1863–1942) was born on 27 November 1863 in the commune of Feldru, district of Năsăud, formerly (until 1851) part of the Austrian military frontier in Transylvania. His life and career illustrate both the social mobility within the political and social framework of the Dual Monarchy, in a family with a tradition in local administration, and the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the change of regime in 1919.

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

His grandfather on his father’s side, Simion Scridon, was a non–commissioned officer in the 17th Border Regiment and mayor of the commune. His father, Teodor Scridon (1834–1920) served eight years in the Habsburg army (1854–1862), rising to the rank of standard bearer. On his return he became mayor of the commune (1865), holding this office almost continuously, sometimes as communal cashier, for 34 years. In 1873 he was one of the founders of the “Feldru Loan and Safekeeping Association”, the first popular bank in the region. In 1863 he married Nastasia Pop, with whom he had five children (three boys and two girls).

Leon Scridon sr. (b. 1863), the eldest of the brothers, attended primary and secondary school in Năsăud, where he graduated from the local gymnasium in 1883. He went on to study law at the University of Cluj/Kolozsvár and obtained his bachelor degree in 1887 and his doctorate in state (administrative) sciences in 1889. During his studies he received a scholarship of 200 Gulden from the “Border Guards’ Funds” (the scholarship funds established from the assets of the former Border Regiment, which were only available to the Grenzer descendants).

In 1893 he married Maria Jarda (1875–1950), with whom he had three children: Ion (b. 1894), Elena (b. 1896) and Leon jr. (b. 1897). Between 1887 and 1922 Leon Scridon sr. pursued an administrative career, first as an official of Bistrița-Năsăud County in the Kingdom of Hungary, then as a county official and prefect in the Kingdom of Romania. In the Kingdom of Hungary, his career followed the linear course of most civil servants of the time. After two years as an administrative trainee (1887–1889), he was appointed notary of the orphanage see (1889–1890), then sheriff (Stuhlrichter/Szolgabíró) (1890–1891), county notary (1892–1906), and chief county notary (1906–1919). Among other things, he was well known locally at the time because his working day started at 5 A.M. In the Kingdom of Romania, opportunities for professional and social advancement increased. Between 1919 and 1921 he was appointed vice-prefect of Bistrița-Năsăud County, and on 29 December 1921 he was appointed prefect of Ciuc County, a position from which he retired a month later, in January 1922, when he reached the age limit required by law (35 years of service).

But this upward path was not without its challenges, especially in the early years after 1918. Immediately after the war, former pre-war Romanian officials retained their positions and many advanced in office (such as L. Scridon sr.), amid the resignation or refuge of Hungarian officials. However, they were not looked upon favourably by the nationalist radicals, who wanted to remove from administrative positions all those who had held office in the former political regime. Even if it did not go that far, the former officials were regarded with distrust. Not only political opponents, but also the armed forces were initially wary of the former officials. A report of the Romanian Volunteer Corps in December 1918 contains a list of public persons of Romanian origin in Transylvania who could be trusted to support the military operations of the Romanian Army in its advance westwards. This list does not include the name of Leon Scridon sr., but it does feature that of his son, Leon Scridon jr., at the time a law student.

Last but not least, the precarious economic conditions in the post-war years made it prone to abuse of office and speculation, with accusations also reaching senior officials. In mid-1919, rumours began to spread about an embezzlement supported by senior officials of Bistrita-Năsăud County, headed by the prefect and vice-prefect, who had allowed the sale, through third party traders of products from the warehouses of the former Habsburg army and had illegally issued export permits for such goods (export meaning that they had been sold outside Transylvania, in Bukovina). The investigation lasted almost half a year and ended with the acquittal of L. Scridon sr., who was reinstated in December 1919. A few months later, on 23 May 1920, amidst the tensions that had built up during the preparations for land reform, a group of 200 or 300 peasants forcibly removed the vice-prefect from office. As 28 of them were arrested, the next day more than 2000 peasants took to the streets in front of the prefect’s office.

The last step in his career, the one towards the position of prefect of Ciuc County, took place in December 1921, right at the end of the Averescu II government (13 March 1920 – 16 December 1921), of which the radical wing of the Romanian National Party, led by O. Goga, was part of. It is possible that his son Leon jr.’s relations with this political grouping contributed to the appointment, and the short period he held the office (just one month) indicates that it was a provisional, almost honorary, position before his retirement.

His relations with the public administration continued after retirement: in 1923 he was president of the county section of the Transylvanian Civil Servants Association, and from 1927 president of the county section of the Pensioners Association.

At the same time, he was also an official of civilian institutions, mostly related to the institutional legacy of the former Border Guards Regiment. He was a member of the General Assembly of the Forestry Funds (1889–1942), a member of the Administrative Commission of the same funds (1896–1923) and an assessor of the commission for the administration of the border guards’ forestry funds. He was also cashier and member of the church committee of the Greek-Catholic parish of Bistrița. Between 1912 and 1913 he took the necessary steps to establish the Romanian Women’s Association in Bistrița, drafted the statutes and was secretary of the Association between 1913 and 1919. His involvement in numerous other associations and charity initiatives was complemented by a similar degree of involvement in the local banking institutions. Between 1904 and 1942 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Aurora” bank in Năsăud, and from 1923 until his death in 1942 he was the manager of the Bistrița branch of the same bank. During 1901–1920 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Bistrițiana” bank (vice-president 1911–1915), and during 1926–1930 a member of the board of directors of “Regna”, a logging company operating in the forests of the border guards communes. He was also a member of the board of directors of the “Hebe” company, which managed the thermal baths in Sângeorz Băi. In short, he had a seat and a say in almost every (if not all) institution that mattered at county level, in all branches of public life, for more than forty years.

When Leon Scridon sr. died in Năsăud, in 1942, part of his family, one of the most respected and well-placed in the former military frontier, was in refuge in Romania after the takeover of Northern Transylvania to Hungary. His son Ion Scridon pursued a medical career. His daughter Elena was married to General Grigore Bălan (1896–1944), who died in 1944 in the battles for the liberation of Transylvania. Leon jr. studied law and at a young age became close to the political group led by Octavian Goga (1881–1938). He was a member of the Romanian Parliament (1937, on the lists of the National Christian Party), secretary of state, then secretary for the Someș land (Ținutul Someș) on behalf of the National Revival Front (1940) and general commissioner for Romanian refugees in Northern Transylvania (1940–1944). After the establishment of communism, he was sentenced twice: once in 1949 by the People’s Tribunal in Năsăud, and a second time in 1955 by the Bucharest Territorial Military Tribunal. He was pardoned and released from prison on 12 September 1955.

The four generations of the Scridon family that succeeded each other between the early 19th and the mid-20th centuries illustrate different patterns of social mobility, at different levels and in different chronological periods and political contexts: the role of tradition and administrative position in what might be called the “rural elite” (Simion and Teodor Scridon); the importance of education for the processes of social mobility taking place from the second half of the 19th century onwards (Leon Scridon sr.); the impact of changes in the political regime on members of the elite (upward in 1919 for Leon Scridon sr., then for his son Leon jr., and downward after 1948 for the latter).

Bibliography

Cornel Grad, Contribuția armatei române la preluarea puterii politico–administrative în Transilvania. Primele măsuri (noiembrie 1918–aprilie 1919), „Revista de Administrație Publică și Politici Sociale”, II, 2010, nr. 4 (5), p. 52–79 (55–56).

Vasile Ilovan, Aspecte ale mișcării revoluționare și democratice în județul Bistrița–Năsăud, „File de Istorie”, II, 1972, p. 167–182 (173–174).

Ironim Marţian, Onisim Filipoiu, Leon Scridon senior (1863–1942), „Buletinul Cercului Științific Plaiuri Năsăudene Bistrița”, IV, 1983, p. 36–59.

Adrian Onofreiu, La cumpăna veacurilor şi a vremurilor. Leon Scridon Sen. în apărarea averilor şi a Liceului Grăniceresc din Năsăud, „Arhiva Someșană”, seria III, 14, 2015, p. 67–85.

Teodor Tanco, Leon Scridon schiţase o istorie nescrisă nici pînă azi, in Teodor Tanco, Virtus Romana Rediviva, vol. 5, Bistrița, 1984, p. 282–286.

Iosif Uilăcan, Leon Scridon, in Adrian Onofreiu, Dan Lucian Vaida (eds.), Convergenţe etnoculturale. In Honorem Mircea Prahase, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2012, p. 291–308.

Press

Patria, I, 1919, 5, 7/20 February, p. 1.

România, III, 1940, 573–583, 8 January, p. 2.

Țara, IV, 1944, 910, June 18, p. 3.

Leon Scridon sr. (1863–1942) was born on 27 November 1863 in the commune of Feldru, district of Năsăud, formerly (until 1851) part of the Austrian military frontier in Transylvania. His life and career illustrate both the social mobility within the political and social framework of the Dual Monarchy, in a family with a tradition in local administration, and the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the change of regime in 1919.

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

His grandfather on his father’s side, Simion Scridon, was a non–commissioned officer in the 17th Border Regiment and mayor of the commune. His father, Teodor Scridon (1834–1920) served eight years in the Habsburg army (1854–1862), rising to the rank of standard bearer. On his return he became mayor of the commune (1865), holding this office almost continuously, sometimes as communal cashier, for 34 years. In 1873 he was one of the founders of the “Feldru Loan and Safekeeping Association”, the first popular bank in the region. In 1863 he married Nastasia Pop, with whom he had five children (three boys and two girls).

Leon Scridon sr. (b. 1863), the eldest of the brothers, attended primary and secondary school in Năsăud, where he graduated from the local gymnasium in 1883. He went on to study law at the University of Cluj/Kolozsvár and obtained his bachelor degree in 1887 and his doctorate in state (administrative) sciences in 1889. During his studies he received a scholarship of 200 Gulden from the “Border Guards’ Funds” (the scholarship funds established from the assets of the former Border Regiment, which were only available to the Grenzer descendants).

In 1893 he married Maria Jarda (1875–1950), with whom he had three children: Ion (b. 1894), Elena (b. 1896) and Leon jr. (b. 1897). Between 1887 and 1922 Leon Scridon sr. pursued an administrative career, first as an official of Bistrița-Năsăud County in the Kingdom of Hungary, then as a county official and prefect in the Kingdom of Romania. In the Kingdom of Hungary, his career followed the linear course of most civil servants of the time. After two years as an administrative trainee (1887–1889), he was appointed notary of the orphanage see (1889–1890), then sheriff (Stuhlrichter/Szolgabíró) (1890–1891), county notary (1892–1906), and chief county notary (1906–1919). Among other things, he was well known locally at the time because his working day started at 5 A.M. In the Kingdom of Romania, opportunities for professional and social advancement increased. Between 1919 and 1921 he was appointed vice-prefect of Bistrița-Năsăud County, and on 29 December 1921 he was appointed prefect of Ciuc County, a position from which he retired a month later, in January 1922, when he reached the age limit required by law (35 years of service).

But this upward path was not without its challenges, especially in the early years after 1918. Immediately after the war, former pre-war Romanian officials retained their positions and many advanced in office (such as L. Scridon sr.), amid the resignation or refuge of Hungarian officials. However, they were not looked upon favourably by the nationalist radicals, who wanted to remove from administrative positions all those who had held office in the former political regime. Even if it did not go that far, the former officials were regarded with distrust. Not only political opponents, but also the armed forces were initially wary of the former officials. A report of the Romanian Volunteer Corps in December 1918 contains a list of public persons of Romanian origin in Transylvania who could be trusted to support the military operations of the Romanian Army in its advance westwards. This list does not include the name of Leon Scridon sr., but it does feature that of his son, Leon Scridon jr., at the time a law student.

Last but not least, the precarious economic conditions in the post-war years made it prone to abuse of office and speculation, with accusations also reaching senior officials. In mid-1919, rumours began to spread about an embezzlement supported by senior officials of Bistrita-Năsăud County, headed by the prefect and vice-prefect, who had allowed the sale, through third party traders of products from the warehouses of the former Habsburg army and had illegally issued export permits for such goods (export meaning that they had been sold outside Transylvania, in Bukovina). The investigation lasted almost half a year and ended with the acquittal of L. Scridon sr., who was reinstated in December 1919. A few months later, on 23 May 1920, amidst the tensions that had built up during the preparations for land reform, a group of 200 or 300 peasants forcibly removed the vice-prefect from office. As 28 of them were arrested, the next day more than 2000 peasants took to the streets in front of the prefect’s office.

The last step in his career, the one towards the position of prefect of Ciuc County, took place in December 1921, right at the end of the Averescu II government (13 March 1920 – 16 December 1921), of which the radical wing of the Romanian National Party, led by O. Goga, was part of. It is possible that his son Leon jr.’s relations with this political grouping contributed to the appointment, and the short period he held the office (just one month) indicates that it was a provisional, almost honorary, position before his retirement.

His relations with the public administration continued after retirement: in 1923 he was president of the county section of the Transylvanian Civil Servants Association, and from 1927 president of the county section of the Pensioners Association.

At the same time, he was also an official of civilian institutions, mostly related to the institutional legacy of the former Border Guards Regiment. He was a member of the General Assembly of the Forestry Funds (1889–1942), a member of the Administrative Commission of the same funds (1896–1923) and an assessor of the commission for the administration of the border guards’ forestry funds. He was also cashier and member of the church committee of the Greek-Catholic parish of Bistrița. Between 1912 and 1913 he took the necessary steps to establish the Romanian Women’s Association in Bistrița, drafted the statutes and was secretary of the Association between 1913 and 1919. His involvement in numerous other associations and charity initiatives was complemented by a similar degree of involvement in the local banking institutions. Between 1904 and 1942 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Aurora” bank in Năsăud, and from 1923 until his death in 1942 he was the manager of the Bistrița branch of the same bank. During 1901–1920 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Bistrițiana” bank (vice-president 1911–1915), and during 1926–1930 a member of the board of directors of “Regna”, a logging company operating in the forests of the border guards communes. He was also a member of the board of directors of the “Hebe” company, which managed the thermal baths in Sângeorz Băi. In short, he had a seat and a say in almost every (if not all) institution that mattered at county level, in all branches of public life, for more than forty years.

When Leon Scridon sr. died in Năsăud, in 1942, part of his family, one of the most respected and well-placed in the former military frontier, was in refuge in Romania after the takeover of Northern Transylvania to Hungary. His son Ion Scridon pursued a medical career. His daughter Elena was married to General Grigore Bălan (1896–1944), who died in 1944 in the battles for the liberation of Transylvania. Leon jr. studied law and at a young age became close to the political group led by Octavian Goga (1881–1938). He was a member of the Romanian Parliament (1937, on the lists of the National Christian Party), secretary of state, then secretary for the Someș land (Ținutul Someș) on behalf of the National Revival Front (1940) and general commissioner for Romanian refugees in Northern Transylvania (1940–1944). After the establishment of communism, he was sentenced twice: once in 1949 by the People’s Tribunal in Năsăud, and a second time in 1955 by the Bucharest Territorial Military Tribunal. He was pardoned and released from prison on 12 September 1955.

The four generations of the Scridon family that succeeded each other between the early 19th and the mid-20th centuries illustrate different patterns of social mobility, at different levels and in different chronological periods and political contexts: the role of tradition and administrative position in what might be called the “rural elite” (Simion and Teodor Scridon); the importance of education for the processes of social mobility taking place from the second half of the 19th century onwards (Leon Scridon sr.); the impact of changes in the political regime on members of the elite (upward in 1919 for Leon Scridon sr., then for his son Leon jr., and downward after 1948 for the latter).

Bibliography

Cornel Grad, Contribuția armatei române la preluarea puterii politico–administrative în Transilvania. Primele măsuri (noiembrie 1918–aprilie 1919), „Revista de Administrație Publică și Politici Sociale”, II, 2010, nr. 4 (5), p. 52–79 (55–56).

Vasile Ilovan, Aspecte ale mișcării revoluționare și democratice în județul Bistrița–Năsăud, „File de Istorie”, II, 1972, p. 167–182 (173–174).

Ironim Marţian, Onisim Filipoiu, Leon Scridon senior (1863–1942), „Buletinul Cercului Științific Plaiuri Năsăudene Bistrița”, IV, 1983, p. 36–59.

Adrian Onofreiu, La cumpăna veacurilor şi a vremurilor. Leon Scridon Sen. în apărarea averilor şi a Liceului Grăniceresc din Năsăud, „Arhiva Someșană”, seria III, 14, 2015, p. 67–85.

Teodor Tanco, Leon Scridon schiţase o istorie nescrisă nici pînă azi, in Teodor Tanco, Virtus Romana Rediviva, vol. 5, Bistrița, 1984, p. 282–286.

Iosif Uilăcan, Leon Scridon, in Adrian Onofreiu, Dan Lucian Vaida (eds.), Convergenţe etnoculturale. In Honorem Mircea Prahase, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2012, p. 291–308.

Press

Patria, I, 1919, 5, 7/20 February, p. 1.

România, III, 1940, 573–583, 8 January, p. 2.

Țara, IV, 1944, 910, June 18, p. 3.

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

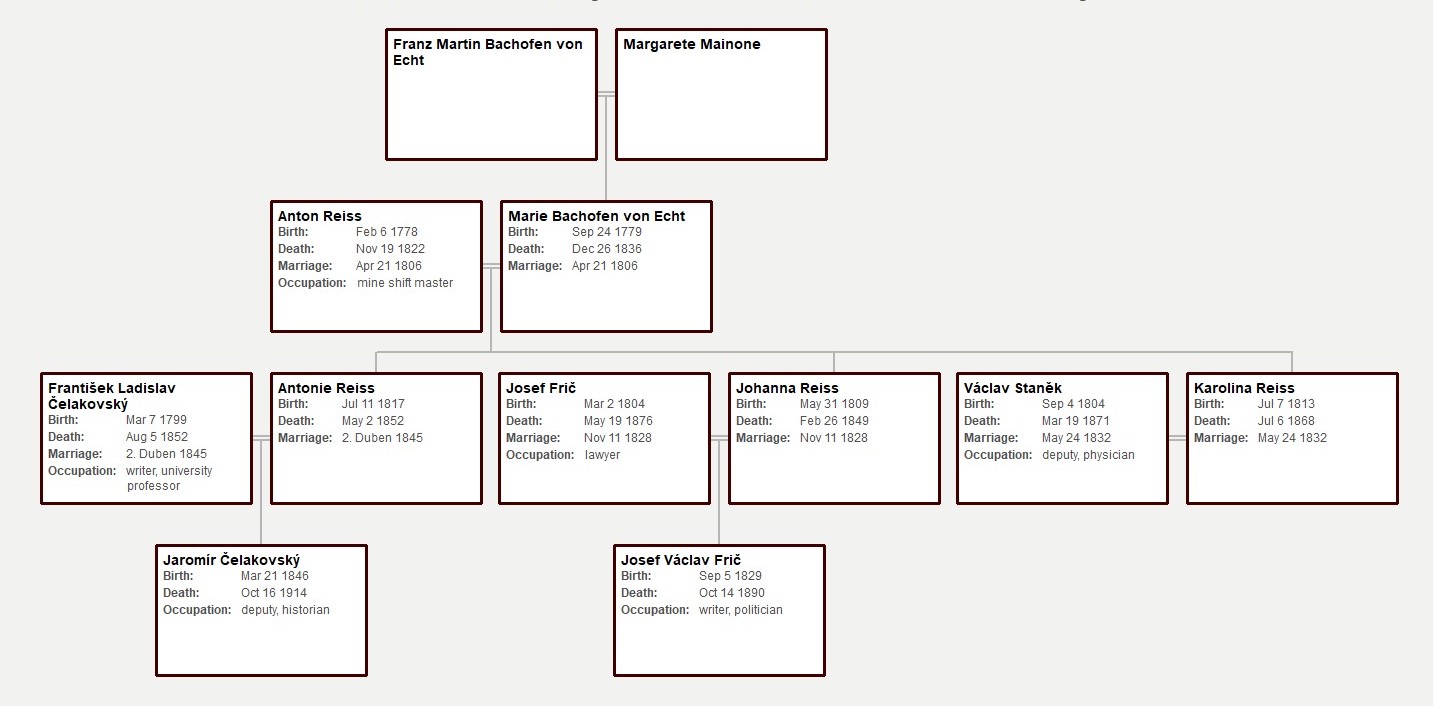

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

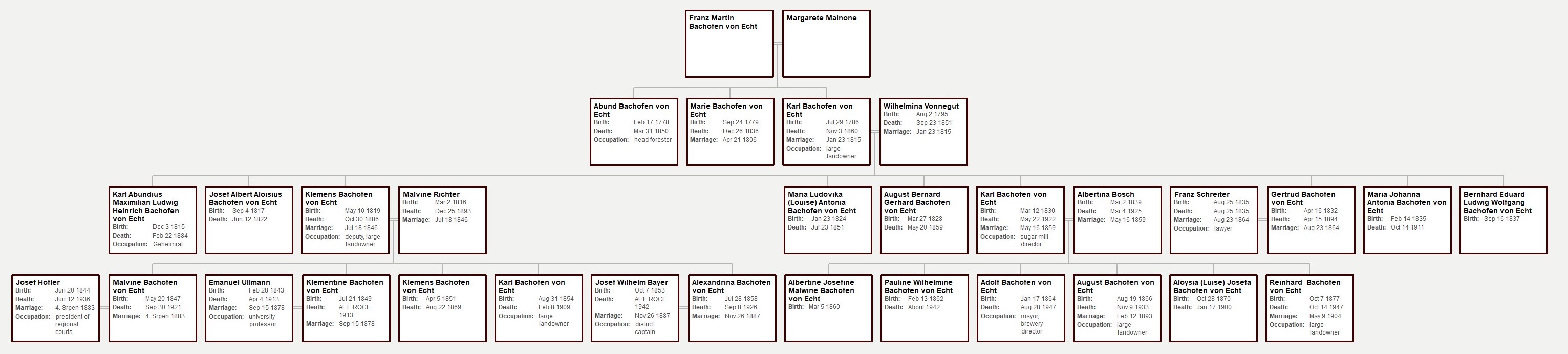

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

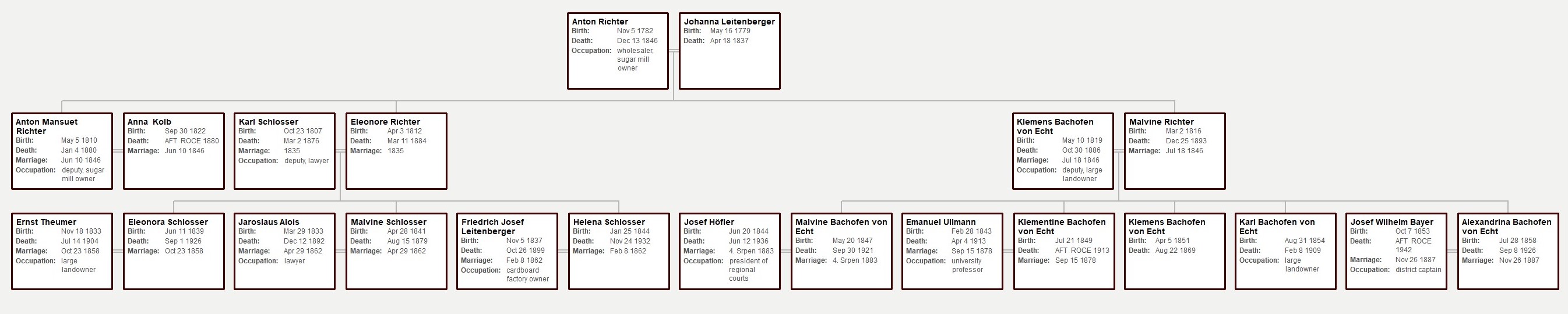

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

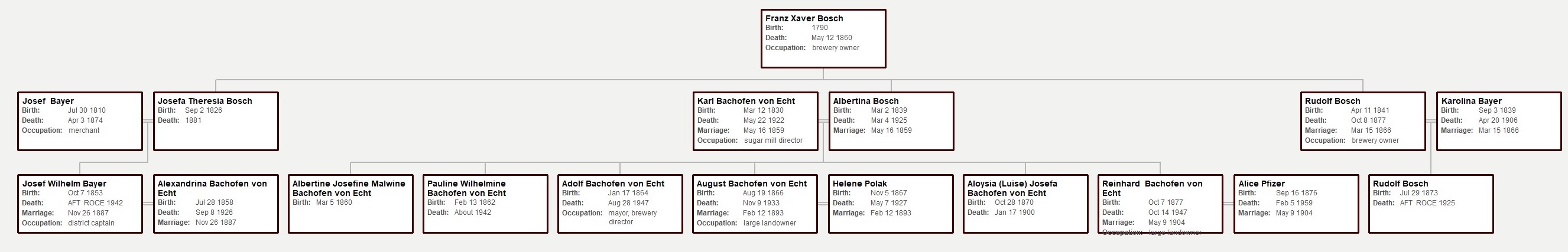

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

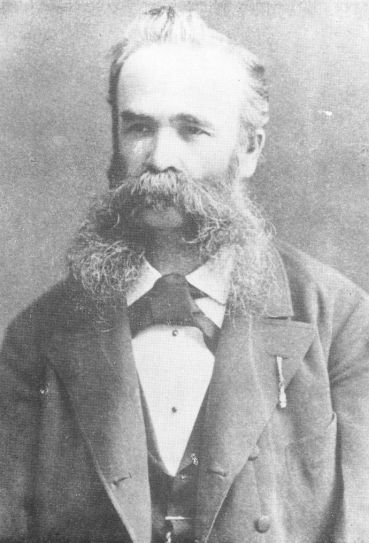

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

Karl Andreas Fabritius (1826–1881), deputy, historian, pastor, teacher, journalist

The Saxon community in the 19th century Transylvania represents an interesting study case for how the changes operated in the entire Habsburg Monarchy manifested at a local level, especially for a group that was German, was a privileged minority in the region and started losing those privileges with the rise of nationalism. The Saxons were brought to Transylvania by various Hungarian kings during the 12th and 13th centuries when it was part of the Hungarian Kingdom. Despite being a demographic minority, they enjoyed longstanding privileges, including land grants, tax exemptions, and the monarch’s protection, even after Transylvania became autonomous under the Ottoman Empire and later the Habsburg Monarchy. However, the situation changed in the 19th century with the emergence of Austria-Hungary and the social transformations of the time. The privileges held by the Saxon community no longer aligned with the new political values of Hungary, which had direct control over Transylvania after 1867, so they were gradually abolished. In response, the Saxons, along with other ethnic groups in Transylvania, adopted various attitudes, influenced by the heterogeneity of political views within their elite. Examining the lives of key leaders within these political groups could provide valuable insight into the impact of these changes and their consequences for individuals. The case of Karl Fabritius offers intriguing insights in this regard. Although he faced massive backlash on the Saxon political scene for his views, he managed to maintain his political position and seat in the Hungarian Parliament, as well as propel some other aspects of his professional life, in the new political climate, which exemplifies the fate of the collaborationists in newly established regimes.

Karl Andreas Fabritius was born on the 28th of October or the 6th of November 1826 in Sighișoara/Schäßburg/Segesvár/, a locality in Transylvania of 3000 inhabitants. From his father’s side, he came from a family attested with the Latin name Fabritius since the 16th century, which gave numerous priests and civil servants. However, the branch of the family of Karl Fabritius was mainly active in crafts and industry, and “belongs to the more prestigious families of Sighișoara due to diligence and marriage connections.”[1] Both his grandfather and his father were craftsmen, the first a tailor, and the latter a bookbinder. His father, also called Andreas Karl Fabritius (1801–1879), married in 1825 Karoline Elisabeth, n. Schuller, daughter of Michael Schuller, a pastor of the Klosdorf/Miklóstelke/Cloașterf branch. Together they had four children: Ottilia (?–1846), who died as an unmarried mother; Sarolta (?–1879), who married a councilor from Sighișoara from Simonis family; Friedrich, who in 1883 was a district judge; and Karl Andreas (1826–1881).

Karl Fabritius studied at the local gymnasium under the guidance of Mihály Gottlieb Schuller (1802–1882), the director of the school, pastor and local personality. Schuller was the son of the pastor Michael Schuller from Cloașterf, thus being K. Fabritius’s uncle on the mother’s side. The relationship with him seemed to have improved Fabritius school performance. He also had as a teacher Georg Daniel Teutsch (1817–1893), a figure that was going to mark Fabritius’s life in major ways later. For higher education, Fabritius wished to pursue a career in law, but at his grandfather’s insistence and with his financial support, in 1847 Fabritius went abroad to study theology and history in Leipzig, where he was involved in the revolution of 1848. Due to financial problems, Fabritius applied later for support from the Austrian government, as well as from Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, a cultural Saxon association from Transylvania, of which he was a member. Still, this was not enough and in 1849 left for Vienna, where he met ministerial school councilor Johann Karl Schuller (1794–1865), who helped Fabritius in his historical pursuits. Fabritius soon moved to Bratislava as an editor for Pressburger Zeitung, and shortly after he received a position at Siebenbürger Bote, a newspaper in Sibiu/Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben, Transylvania. This was the reason for his return to his homeland in August 1850. However, Fabritius’s ideas were not well received by the owners of the newspaper, and he was fired after a month.

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Karl Fabritius, cca 1850.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.

In October 1850 Fabritius obtained a position as a teacher at the gymnasium in Sighișoara, where G. D. Teutsch was a director at the time. Together with his former teachers M. Schuller and G. D. Teutsch, Fabritius also got more involved in the activities organized by Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde, and through it, he started disseminating his historical research on which he worked since his studies. Due to some conflicts between the school’s director and the local consistory, Fabritius lost his teaching position in 1855, but soon after he was elected as a second town preacher in Sighișoara, a position much better paid than the one of a teacher. His luck changed afterwards. Fabritius applied for a pastor position in Merghindeal/Mergeln/Morgonda and Stejărișu/Probstdorf/Prépostfalva in 1857, then in Apold/Trappold in 1859. However, he did not succeed in any place, possibly because of his friendship with G. D. Teutsch. In 1861 Fabritius was named the first city preacher, but in reality, his salary was lower than before. He applied again for a pastor position in Brădeni/Henndorf/Hégen in 1865, but he was rejected.

K. Fabritius entered the political scene in 1867, at the time of the political compromise between Vienna and Pest that lead to the establishment of Austria-Hungary. He also became the “spiritual leader” of the “Young Saxons,” a political group of Transylvanian Saxons with liberal leanings and which considered collaborating with Pest, as well as with the other ethnic groups. This was in opposition with the political passivity adopted by the “Old Saxons”, the rival political group on the local scene. Between 1867 and 1881 Fabritius was elected five times as a deputy for Sighișoara on the lists of the governmental parties. He also became pastor in Apold in 1868. The sources do not mention any reason why K. Fabritius insisted on this village again, however, a branch of the Fabritius family had a few members that had previously been pastors or were connected to Apold. In 1872 Fabritius became a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Science, which further facilitated his historical research. In 1876, he received the opportunity to be appointed school inspector and even Lord-Lieutenant. Fabritius refused both positions, the reason being that he did not want any personal gain just for being a deputy.

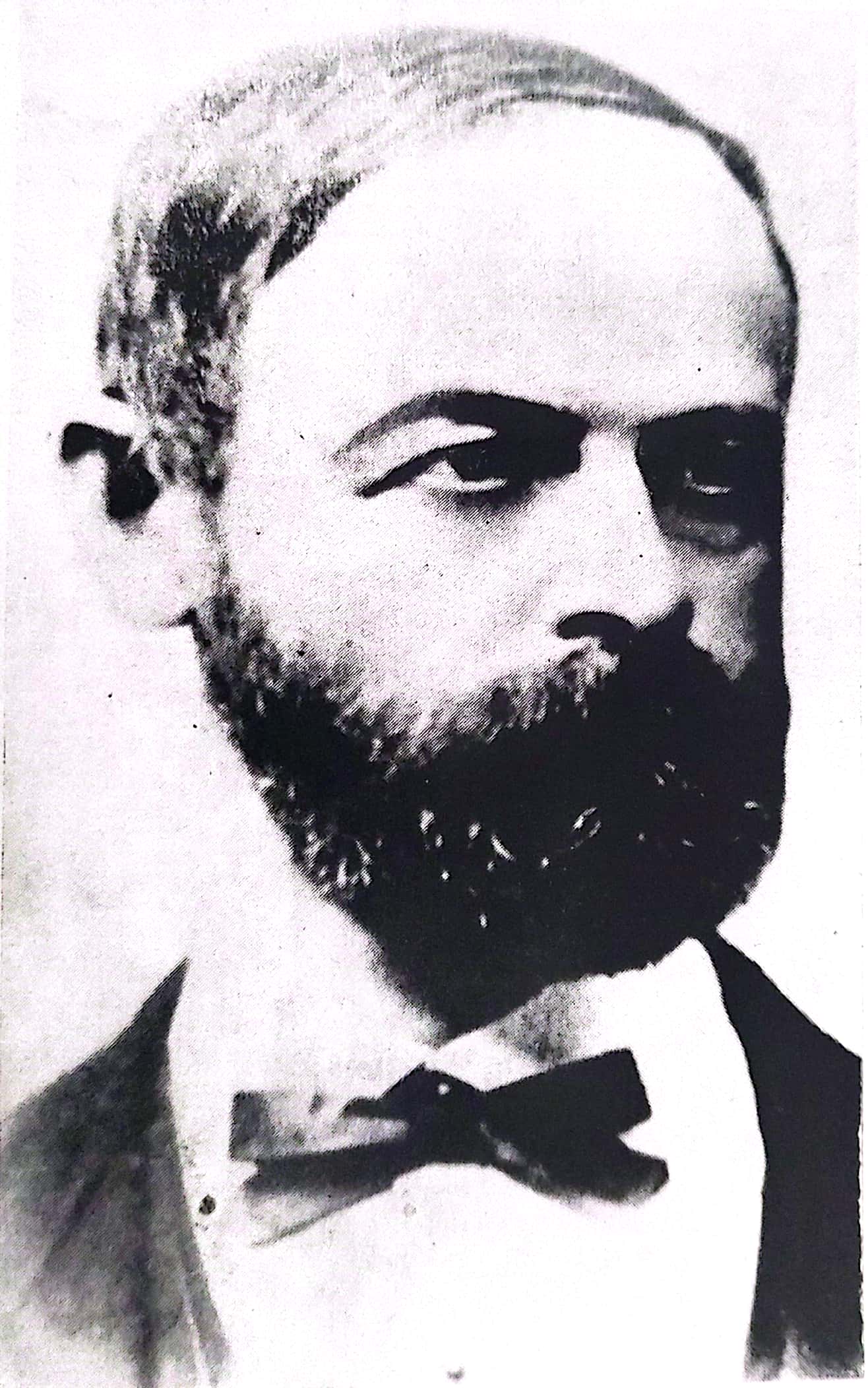

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

Albert Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881) Hungarian poet, dramatist, journalist, and politician, and Karl Fabritius.

However, Fabritius’s liberal and collaborationist political attitude with the Hungarian governmental party produced a rupture in his relationship with G. D. Teutsch, who after 1867 became the leader of the “Old Saxons.” Already at the beginning of his second mandate, Fabritius started receiving personal attacks from the opposition’s press. In 1872 Fabritius mentioned to his family his thoughts of quitting politics, because of the harassment he received, mentioning that he was continuing only to get access to the archives and libraries in Budapest. The attacks did not stop only at the political level. G. D. Teutsch became bishop of the Evangelical Church in Transylvania in 1867, and the president of Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde in 1869. Teutsch criticized Fabritius’s historical writings and prevented their publication by the Verein für siebenbürgische Landeskunde. Moreover, Teutsch questioned Fabritius on whether he could fulfill his duty in his parish, given his frequent trips to Budapest. The scandal gained proportions around 1875–1876 when Fabritius encountered difficulties in being reelected and received death threats. In 1879, Fabritius quit his position as pastor in Apold. Afterwards, he expressed he wanted to focus just on his historical research and less on politics, given the political losses for the Transylvanian Saxons in the past decade, although Fabritius still had a mandate. However, 1879 is also the last year he published something, his works afterward remaining in manuscript. An accident in the Budapest University Library in December 1880 probably also contributed to this. Fabritius was injured and this led to his death on 2nd February 1881.

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Karl Fabritius, 1880.

Source: Göllner, Karl. Carl Fabritius. Leben Und Wirken, București: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1975.