Maximilian Obentraut (1795–1883). A mysterious origin of a County President

In the modern society of the 19th century, illegitimate origin was still one of the most painful social stigmas that an individual could bring with him or her into life. The absence of a father, the precariousness of the family background, usually combined with a lack of financial resources and the difficulty securing the livelihood for the mother and child did not offer very good prospects for the individual’s social position, provided he or she lived to adulthood at all. In addition, there were various restrictions concerning studies, scholarships or admission to the civil service, which required the submission of a baptismal certificate and which immediately made it clear what background the applicant came from. In this respect, illegitimate children of the higher social classes represented a certain exception. Although illegitimacy in the milieu of the royal court and the aristocracy was no less undesirable from the point of view of the Church than it was for the general population, the range of possibilities for taking care of an illegitimate child was much wider. Moreover, conceiving and giving birth to a child out of wedlock was decriminalised by the Enlightenment reforms, and in this regard, demographers speak of the first sexual revolution, when baptismal registers began to be filled with children for whom the slot for the father’s name remained empty.

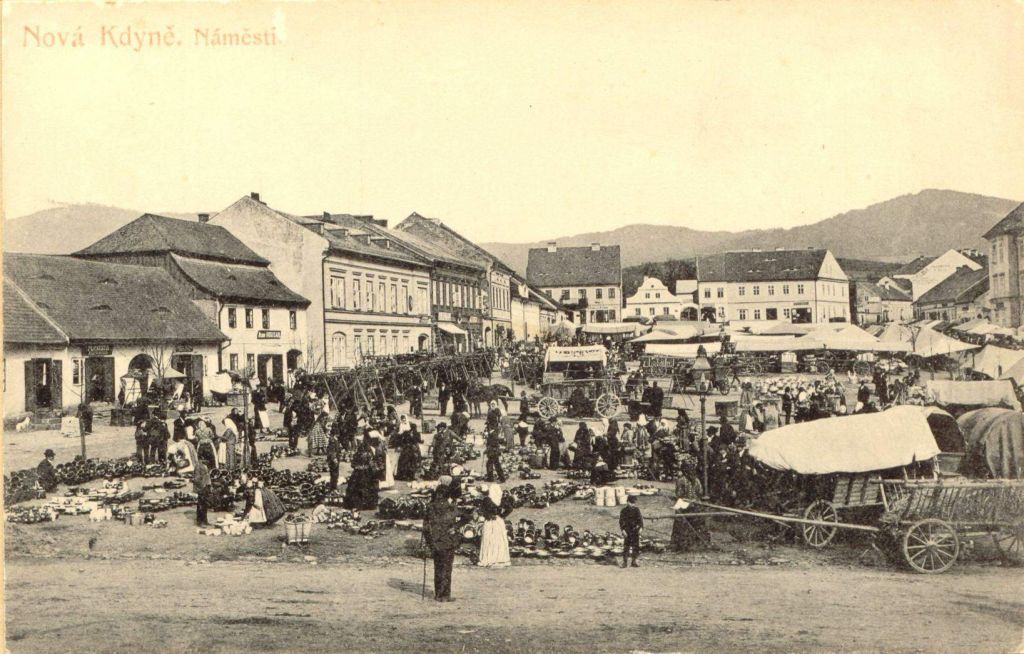

Maximilian Obentraut was born as an illegitimate child under dramatic circumstances on 12 October 1795, in a coaching inn on the square of the West Bohemian town of Kdyně/Neugedein. The baptismal register says very little on his birth, the father of the child is missing and the mother is given as a certain Anna, daughter of the chief estate administrator František Obentraut from Mnichovo Hradiště/Münchengrätz. However, this is obviously a fictitious name since no such official can be traced in the archival sources. The later brilliant career of Maximilian (named after his patron saint on the day of his birth) as a civil servant gave rise to a whole range of conjectures and speculations about his origin, and even became the subject of a fictional story by the local writer and Catholic priest Jindřich Šimon Baar (1869–1925). In his novel Lůzy, he vividly describes both the boy’s birth and his later upbringing and education.

We may assume that in his historical novels Baar reflected local narratives or stories which he may have heard from his fellow clergymen, and which, incidentally, can be supported by a large amount of circumstantial evidence and various strange circumstances connected with Obentraut’s origins and his civil-service career. His mother is identified by some other authors as Countess Marie Anna Stadion (1775-1841), the young wife of the former imperial ambassador Johann Philippe II Count Stadion (1763-1824), who resided at the Stadion estate in Kout/Kauth in Šumava, only a few kilometres from Kdyně. Her pregnancy during her husband’s long-term absence was obviously a serious problem that had to be kept as a secret, but during a trip to an undisclosed location – at least according to local tradition – the countess gave birth prematurely. She was forced to deliver the child unexpectedly in a country inn, but her maid insisted at least they have a private room to which only the local midwife and priest were allowed access. The next morning, the mother abandoned her child and the new-born boy was taken in by the midwife, whose son together with the inn’s waitress were his godparents at the baptism which took place at the inn still on the same day and was performed by the local priest, chaplain Martin Hufner. It was Hufner who took charge of the child afterwards, and according to Baar, the mother entrusted the child to him directly after he had confessed her and given her absolution after the birth.

The young Obentraut spent his childhood and youth in Hufner’s care and in 1798, at the age of three, he moved together with him to the nearby pilgrimage site of Tanaberk, where the Roman Catholic priest became parish priest at St. Anne’s church. Obentraut’s foster father probably also took charge of his education and subsequently supported him when Maximilian went to school in Domažlice and the Piarist grammar school in Pilsen. After graduating from the grammar school, Obentraut enrolled at the law faculty in Vienna. This seemed to be a rather unusual choice, given that he could have studied law at Prague university, where his foster father could have easily secured him a good reception among his clergy friends and from the circles of the first Czech Revivalist generation. Moving to Vienna was undoubtedly a more costly option in this respect.

Even as an illegitimate child, Maximilian Obentraut received a first-class education, thanks to his foster father’s effort to ensure that in future the orphan would find a suitable and successful employment in the society. In order not to impair the future career of the young student, it was also necessary to somehow obtain a false baptismal certificate, indicating fictitious parents: his father, Karl Obentraut, k. k. Rittmeister (captain) of the Cuirassier Regiment, and his mother, Anna, née Herold.

The freshly graduated lawyer must have probably used his fake baptismal certificate at the young age of 26 in order to enter the civil service when he became a trainee at the County Office (Kreisamt) in Mladá Boleslav/Jungbunzlau. This is where his career of a political administration official began. In February 1849, the then Interior Minister Franz Seraf Count of Stadion (1806–1853) – if we accepted the possibility that Obentraut was related to the Stadion family, Franz would have been his half-brother – nominated him for the position of county governor (Kreishauptmann) in Jičín/Gitschin. At that time, Stadion was already preparing a comprehensive reform of the public administration, which after the abolition of serfdom lost its traditional arrangement in the form of manors and magistrates of royal towns. Thus, although the former counties in their mid-18th-century form were to exist for only a few more months, by his appointment Obentraut had secured a favourable starting position in the new system. In it, he first occupied the position of one of the seven county presidents who according to Stadion’s idea of the monarchy’s organisation were to play an absolutely crucial role (even more important than the governors themselves).

With the accession of Alexander Bach to the post of Interior Minister and the promulgation of the “organic governance” by the so-called New Year’s Eve Patents (Silvesterpatente), it was obvious that a further reorganization of the structure of public administration would follow. At the time, Obentraut was appointed to the post of head of the Releasing Commission. In this position, he was in charge of the complex system of settling the serfs’ obligations and debts to their former landlords, the burden and payment of which was partly assumed by the state and its administration. In the rank of ministerial councillor, Obentraut was among the highest-ranking officials of the country, who were in direct contact with the Governor and the Minister of the Interior. Especially the Governor held him in high esteem, and so in January 1853 Obentraut was again appointed to the position of county president, this time of the key Prague region, and subsequently also to a position on the so-called organisational commission preparing the new administrative arrangement. A year later, the Emperor rewarded him for these merits with the Knight's Cross of the Order of Leopold. This decoration gave Obentraut an automatic possibility of ennoblement, which he promptly took advantage of and was knighted in 1855. Again, the ennoblement documents contained no information about his real origin or his alleged ancestors.

From the position of an illegitimate child, Maximilian Oberntraut managed to place himself among the social elite of his time. His high position within the newly established state administration was also reflected in the career opportunities of his children. Of the four sons who survived to adulthood, three graduated from the law faculty in Prague and, like their father, entered the service in the political administration. Although Maximilian after several years of practice chose a career as a notary, the other two sons remained loyal to the service of the state and the Emperor and attained equally important positions as their – illegitimate – father.

Literature

Literatura

Gustav Hofmann, Ještě k původu a životě Maxmiliána Obentrauta, Sborník Muzea Chodska v Domažlicích, 1997, pp. 18–23.

Jan Prokop Holý, „Záhadná“ osobnost rytíře Maxmiliána z Obentrautu, Zpravodaj města Horšovský Týn 2005, No. 3, p. 16.

Rudolf Šlajer, Tajemný příběh rytíře Maxmiliána, Kdyňsko 5 (2009), No. 1, p. 8