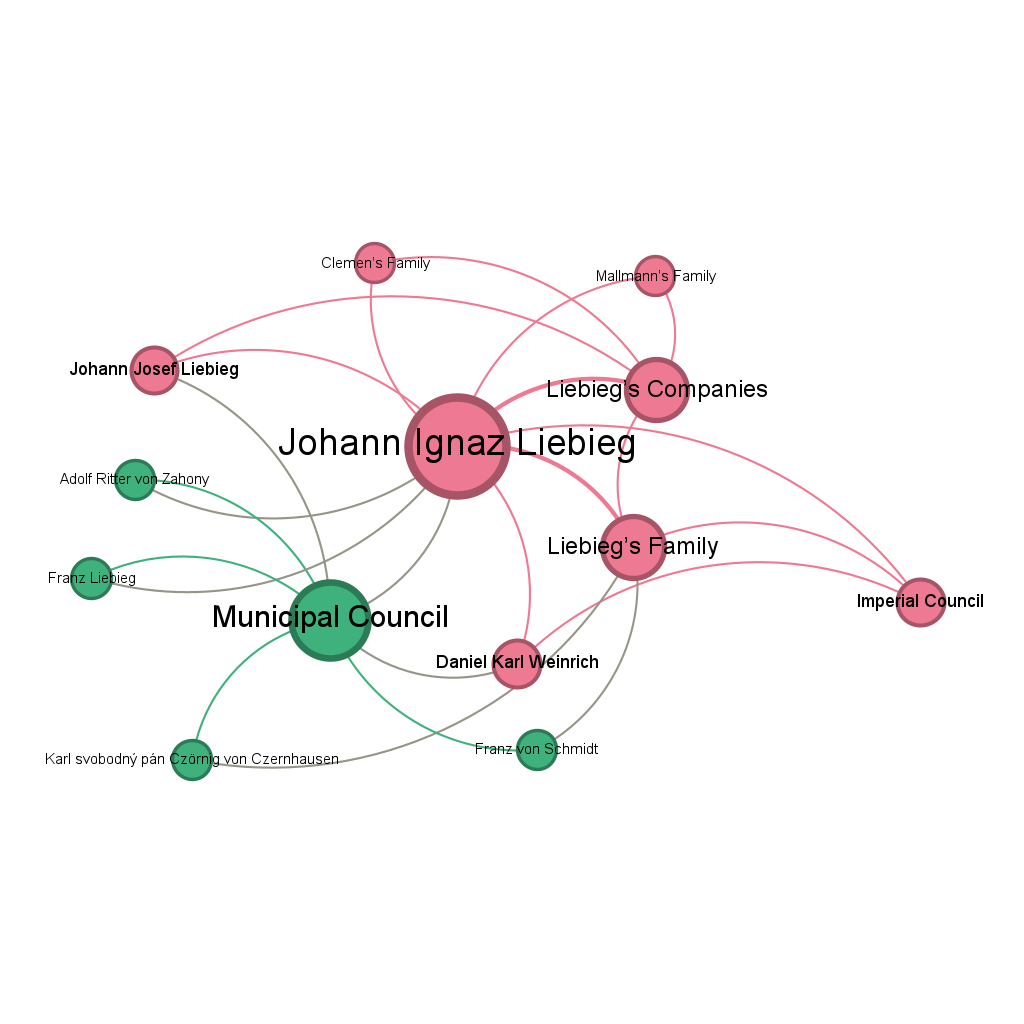

Family of Johann Ignaz Liebieg

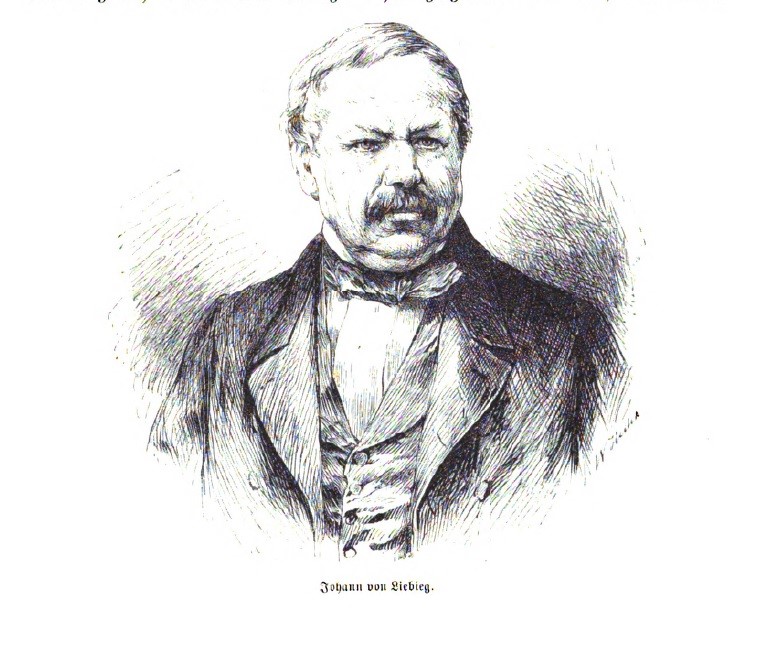

Johann Liebieg Österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, s. 661

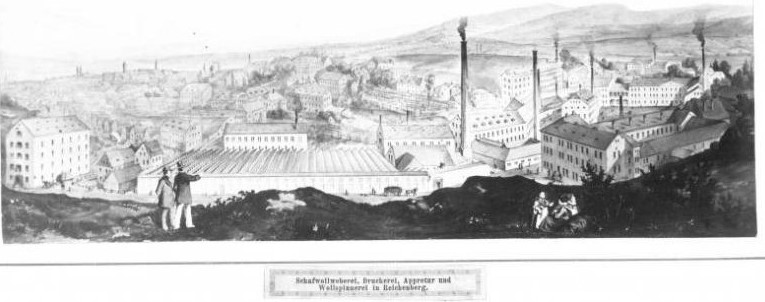

Johann Ignaz Liebieg (1802–1870, newspaper entries of funeral and obituary) personifies one of the most successful businessmen and industrialists in the Habsburg monarchy of the 19th century. Johann Ignaz belonged to the so-called Gründer generation; in cooperation with his brother and other family members, he managed to build a huge textile empire in the Liberec region, which lasted for several generations, surviving the turbulent periods of workers' strikes, economic crisis and both world wars. Johann Ignaz Liebieg became involved in public life at the beginning of the 1850s as a co-founder and leader of the Liberec Chambers of Commerce, co-founder of the Liberec Savings Bank, between 1851–1859 he was president of the Liberec Chambers of Commerce and Trade and in 1851–1864 a city representative. In the 1960s, his public representative activities led to the highest councils - he sat in the Bohemian Diet and in the Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna for the curia of Czech cities. However, he ended his political engagement after three years by relinquishing his mandate. Johann Ignaz Liebieg was primarily a factory owner and entrepreneur. He devoted his life to taking care of the family business to ensure a better livelihood for his children. In 1868, Johann Ignaz Liebieg was elevated to the hereditary status of free lords for his services to the upliftment of industry.[1]

Johann Ignaz Liebeig Ein Arbeiterleben Geschildert von Einem Zeitgenossen

Arms of Liebiegs

Johann Ignaz Liebieg was born into the family of Franz (1769–1811), a Broumov burgher, draper and merchant. Textiles also had a tradition in the Liebieg family. Already Johann Ignaz's great-grandfather was a burgher from Broumov and made his living as a braider, and his grandfather Joseph Liebieg was a cloth merchant. Johann's other two siblings lived to adulthood, the first-born Franz Joseph (1799–1878) and their youngest sister Pauline (1808–1883). The father died prematurely when the eldest Franz Josef was 12 years old, and the mother was responsible for the upbringing of the children. Her relatives occasionally helped her with her three offspring in Broumov. Johann Ignaz was apprenticed to the Broumov master weaver and friend of his late father, Kaspar Werner, and then spent several months as a journeyman travelling "for experience". In 1819, Johann Ignaz settled in Liberec, where he was later joined by his older brother. The two siblings ran a small goods shop, in which their sister Pauline also helped them. Thanks to Franz Josef's experience and thrift, Johann Ignaz's business talent and innovative ideas, as well as the right selection of goods, the brothers were able to expand their shop and warehouses. Soon they also bought their first factory and the family business gradually began to expand.[2]

Johann Ignatz Karl Liebieg

Johann Ignaz Liebieg subordinated one of their business strategies, marriage policy, to the successful family business. In August 1832, at the age of 30, Johann Ignaz Liebieg married Maria Theresa Münzberg (1810–1848), the daughter of a merchant and textile manufacturer from Jiřetín pod Jedlovou.[3] Her father, Anton Münzberg (1765–1823), owned a linen, cotton and woollen goods factory. In 1820 he built a family villa in Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, connected with a complex of factory buildings.[4] Johann Ignaz invested the considerable dowry brought into the marriage by Maria Theresa in the expansion of his business.[5] Maria Theresa died at the age of 38 as a result of pulmonary paralysis, leaving behind a widower, Josef Ignaz, with nine[6] children.[7] In 1853, less than five years after his wife's death, Josef Ignaz remarried. His second wife was Marie Ludovica (1830–1891), née Jungnickel, granddaughter of Anton Münzberg.[8] Four sons were born to Johann Ignaz from his second marriage.[9]

Johann Liebieg

Johann Ignaz built a large family in the style of the Austrian Biedermeier. On the one hand he strove to provide for his family by expanding his business, on the other hand, he prudently ensured the continuity of the family company.[10] Johann Ignaz Liebieg married five daughters (the eldest, Maria Paulina, never married) and four sons (two of whom married after their father's death). No correspondence has survived in the family archives that sheds light on the Liebieg children's choice of partners. It can be assumed, however, that these were 'good catches' for all involved (the Liebigs), who had the potential to preserve and expand the family fortune, to advance up the social ladder, and were personalities with undeniably interesting contacts and access to information. The partners of Liebieg's descendants were either businessmen involved in the family business or landowners and politicians with influence at local or provincial level. At the same time, joining the Liebieg empire may have offered some partners an extension of their own business activities within the Habsburg monarchy.

Maria Theresia Münzberg Maria Luisa Jungnickel

Members of the two German merchant families Mallmanns and Clemens joined the Liebieg family business after their marriage. Both families came from the Rhineland, the Mallmanns from Boppard and the Clemens from nearby Koblenz. Josef Mallmann, the husband of Adelina Liebieg,[11] traded overseas, and in Paris he and his brother Gerhard (and husband of Adele's sister Hermine) ran the export firm Mallmann et Co. The Mallmann brothers had business contacts in Europe, South and North America, the Caribbean, India and China. After his marriage to Adelina, Joseph Mallmann became a partner in Liebieg's company and took over the management of its Vienna branch. In addition to his many business activities, he also served as president of the South-North German Connecting Railway (between Pardubice and Liberec) and the Austrian North-Western Railway (Děčín-Vienna connection).[12] Josef Mallman became an Austrian citizen and for his services he was knighted in Austria.[13]

Factory of Johann Liebieg

Liebieg's son Theodor (1840–1891) married Angelika Clemens (1847–1919), daughter of the merchant and banker Johann Peter Clemens from Koblenz. Theodor Liebieg belonged to the second generation of Liebigs who inherited and managed the North Bohemian textile empire. After his marriage to Angelika, his two brothers-in-law, Gisbert and Leo Clemens, joined the management of the company.

In addition to merchants and businessmen, as mentioned above, the Liebieg family included landowners with representation in the land diets and the Austrian Imperial Council. Adolf Ritter von Zahony (1833–1907), the owner of the farm and castle in Bohemia and husband of Leontina Liebieg, sat in the Bohemian Diet.[14] Ritter von Zahony sat in the Landowners' Curia for the Party of the Constitutional Landowners (1872–1883). Daniel Weinrich (1843–1926),[15] husband of Marie Liebieg and owner of an estate in Bohemia, also held a seat in the same curia and party. In 1872–1883 and 1901–1907 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Diet for the Landowners' Curia, and later a member of the Imperial Council (1873–1878), where he represented the Party of the Constitutional Landowners.[16]

At the Austrian diets were: Bertha Liebieg's husband, Karl Reichsfreihrer von Gagern (1846–1923). Karl von Gagern was a member of the Upper Austrian Diet for the Landowners' Curia. Von Gagern served in the diplomatic service and was appointed Legation Councillor in The Hague in the late 19th century.[17] Leopold Mayr, a builder, architect and vice-mayor of Vienna, was also a member of the Lower Austrian Diet. Leopold Mayr was the father-in-law of Johann Josef Liebieg (1836–1899).

From the point of view of social networking, not only those marriages of Johann Ignaz's children that were contracted and where his business acumen was evident are of interest, but also those that did not take place. One example can be reconstructed. Johann Ignaz's step-aunt Franziska and her husband Peter Fügner imagined for their children a career similar to that of the Liebieg brothers."Johann Liebieg (1802–1870), the founder of the famous Liberec factories, was a role model for both his father and mother, and they made no secret of their wish that their son Jindřich would either show similar business agility to their relative or at least marry into the family of this famous Liebieg."[18] In the end, however, Jindřich Fügner (1822–1866) showed neither "liberalistic energy and fierceness" nor interest in becoming part of the Liebieg clan.[19] He found his niche in physical education and became one of the founders of the Czech gymnastic association Sokol. According to surviving reports, the marriage of Jindřich Fügner to the Liebieg's eldest daughter, Maria Paulina, was probably considered. The family's interpretation of events in the memoirs of Fügner's daughter Renata Tyršová gives the impression that the emotional Jindřich did not want to be part of the predatory and expanding Liebieg empire. On the other hand, it is worth considering that he was not chosen by Johann Ignaz Liebieg. In fact, the same source describes the beginnings of the business career of Jindřich Fügner, who, although had travelled extensively in Europe and supplemented his education with a private tutor in Prague, had no entrepreneurial spirit and no desire to become involved in business in any way. For Johann Ignaz Liebig, he could not have been the ideal partner to whom he could later hand over a share in the family business.

From the point of view of social networking, not only those marriages of Johann Ignaz's children that were contracted and where his business acumen was evident are of interest, but also those that did not take place. One example can be reconstructed. Johann Ignaz's step-aunt Franziska and her husband Peter Fügner imagined for their children a career similar to that of the Liebieg brothers."Johann Liebieg (1802–1870), the founder of the famous Liberec factories, was a role model for both his father and mother, and they made no secret of their wish that their son Jindřich would either show similar business agility to their relative or at least marry into the family of this famous Liebieg."[18] In the end, however, Jindřich Fügner (1822–1866) showed neither "liberalistic energy and fierceness" nor interest in becoming part of the Liebieg clan.[19] He found his niche in physical education and became one of the founders of the Czech gymnastic association Sokol. According to surviving reports, the marriage of Jindřich Fügner to the Liebieg's eldest daughter, Maria Paulina, was probably considered. The family's interpretation of events in the memoirs of Fügner's daughter Renata Tyršová gives the impression that the emotional Jindřich did not want to be part of the predatory and expanding Liebieg empire. On the other hand, it is worth considering that he was not chosen by Johann Ignaz Liebieg. In fact, the same source describes the beginnings of the business career of Jindřich Fügner, who, although had travelled extensively in Europe and supplemented his education with a private tutor in Prague, had no entrepreneurial spirit and no desire to become involved in business in any way. For Johann Ignaz Liebig, he could not have been the ideal partner to whom he could later hand over a share in the family business.

Johann Ignaz prepared his children for a very different entry into life than he himself had. His descendants received a private education and the opportunity to study at foreign universities, inherited a noble title, social status and a fortune estimated at 30 million guldens in his time. Each handled their inheritance differently, according to their own values and individual convictions. However, one can observe a continuity of ties to foreign businessmen and merchants and a striving for inclusion in higher noble society. From the point of view of maintaining the family business, Johann Ignaz did everything possible to ensure that the transfer to the new generation went smoothly. Coincidentally, in the third generation, the company passed to his grandson Theodor Liebieg (1872–1939), who ran it successfully for almost 50 more years. Political reasons finally deprived the heirs of the Liebieg empire of all their property in Bohemia (worth 140 million Czechoslovak crowns) in the 1940s.

[1] National Archives, ČZS, ka. 201, 201b, fol. 657, Liebieg Johann.

[2] Např. ANSCHIRINGER, Anton: Johann Liebieg. Ein Arbeiterleben Geschildert von Einem Zeitgenossen. Leipzig: Verlag von Otto Spamer, 1871; Franz Liebieg. Wien: Selbst-Verlag, 1873; Allgemeine deutsche Biographie. Bd. 18, Lassus – Litschower. Leipzig: Duncker&Humblot, 1883; MALÝ, Jakub. Stručný všeobecný slovník věcný: (malý slovník naučný). Díl VIII. V Praze: I. L. Kober, 1884, s. 168; MERAVIGLIA-CRIVELLI, Rudolf Johann. J. Siebmacher’s Großes und Allgemeines Wappenbuch. IV/9. Der Böhmische Adel. Nürnberg 1886, s. 77, Taf. 48; ERSCH, Johann Samuel. Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetischer Folge. Zweite Section. H–N. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1889, s. 372–374; PETHES, Justus. Gothaisches genealogisches Taschenbuch der freiherrlichen Häuser. Dreiundvierzigster Jahrgang. Gotha 1893, s. 518–520; Ottův slovník naučný: ilustrovaná encyklopaedie obecných vědomostí. Část 15. V Praze: J. Otto, 1900, s. 1051; WIESINGER, Udo B. "Liebieg, Johann Freiherr von". In: Neue Deutsche Biographie, 14 (1985), s. 493–494 [online]. Dostupné z: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd137847602.html#ndbcontent (cit. 26. 6. 2022). Dále např.: SCHILLER, Karl. Umrisse einer allgemeinen Geographie: mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Oesterreich. Umrißeeiner Handels-Geographie für Deutschland und insbesondere Oesterreich: mit einschlagender Lectüre. Zweiter Theil. Wien: Druck von Anton Schweiger, 1864. s, 84–87; RESSEL, G. A.: Nordböhmisches Industrie-Album: die Stättenheimischer Arbeit in Wort und Bild. I. Heft. Teplitz: Im Selbstverlag, 1874, s. 3–14; Die Österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild. Böhmen (2 Abtheilung). Band 15. Wien: K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1896, s. 660–662; RESSEL A.: Verdiente Männer aus Ostböhmen als Wappenerwerber. In: Jb. d. Dt. Riesengebirgs-Ver. f. d. J. 1927, 16. Jg., 1927, s. 24-58. Z novějších prací: RANDÁK, pozn. 1, BERGMANNOVÁ, pozn. 2, HLAVÁČ, Miroslav M. Tvůrci českého zázraku. Praha: APS Agency, 2000, s. 111–114; MYŠKA, Milan. Historická encyklopedie podnikatelů Čech, Moravy a Slezska do poloviny XX. století. Ostrava: Ostravská univerzita, 2003, s. 273–278. Franz Liebieg, pozn. 3; ERSCH, Johann Samuel. Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste in alphabetischer Folge. Zweite Section. H–N. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1889, s. 372–374.

[3] State Regional Archives in Litoměřice (hereinafter referred to as SRA Litoměřice), Roman Catholic Parish Office (hereinafter referred to as FÚ) Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, Register of Marriages 1784–1840.

[4] National Heritage Institute, Monument Catalogue, Vila Antona Münzberga. [online]. Available from: https://www.pamatkovykatalog.cz/vila-antona-munzberga-15548297 (Cited 26. 6. 2022).

[5] MYŠKA, Note 2, p. 274.

[6] Josef Ignaz Liebieg and Maria Theresia Münzberg had a total of 11 children, two of whom died a few months after birth: first-born Ludwig (*† 1833), daugter Ida (1844–1845).

[7] SRA Litoměřice, FÚ Liberec, Register of Deaths 1824–1848.

[8] SRA Litoměřice, FÚ Jiřetín pod Jedlovou, Register of Marriages 1841–1876. Anton Münzberg married three times in total. From the first marriage in 1787 14 children were born, in 1800 twins, one of them was Francisca, later married to Johann Jungnickel. With his second wife Anton Münzberg had a daughter Maria Theresia, married in 1832 to Johann Liebieg. At that time, her older half-sister Francisca already had a two-year-old daughter Maria Ludovica Caroline, the future second wife of Johann Ignaz Liebieg. Liebieg thus married first Anton Münzberg's daughter from his second marriage and then his granddaughter from his first marriage.

[9] Of his four sons from his second marriage, died in infancy Oscar (*1855–†1856).

[10] HLAVAČKA, Milan a BEK, Pavel. Rodinné podnikání v moderní době. Praha: Historický ústav, 2018. p. 26–29.

[11] SOA Litoměřice, FÚ Liberec, Register of Marriages 1848–1861.

[12] MARSCHNER, Erhard. Mallmann, Josef Ritter von. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 15, Duncker&Humblot, Berlin 1987, p. 737.

[13] MARSCHNER, Erhard. Mallmann, Josef Ritter von. In: NeueDeutscheBiographie (NDB). Band 15, Duncker&Humblot, Berlin 1987, p. 737.

[14] Die Arbeit, 1907, 14. Jahrgang, No. 981 (4. August 1907), p. 4.

[15] Weinrich, Daniel Karl (Karl Daniel)“. In: Republik Österreich Parlament [online]. Available at: https://www.parlament.gv.at/WWER/PARL/J1848/Weinrich.shtml (Cited 14. 7. 2022).

[16] WURZBACH, Constantin von. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthum Oesterreich. Wien: Druck und Verlag der k. k. Hof – und Staatsdruckerei, 1886, p. 58–61.

[17] (Linzer) Tages-Post, 59. Jahrgang, No. 8 (12. Jänner 1923), p. 4.

[18] BARTOŠ, Josef. Vývoj osobnosti Jindřicha Fügnera. Sokol, 1933, Year. 59, No. 12, p. 258–264.

[19] TYRŠOVÁ, Renata. Jindřich Fügner: paměti a vzpomínky na mého otce. Part 1. Praha: Český čtenář, 1924, p. 30.

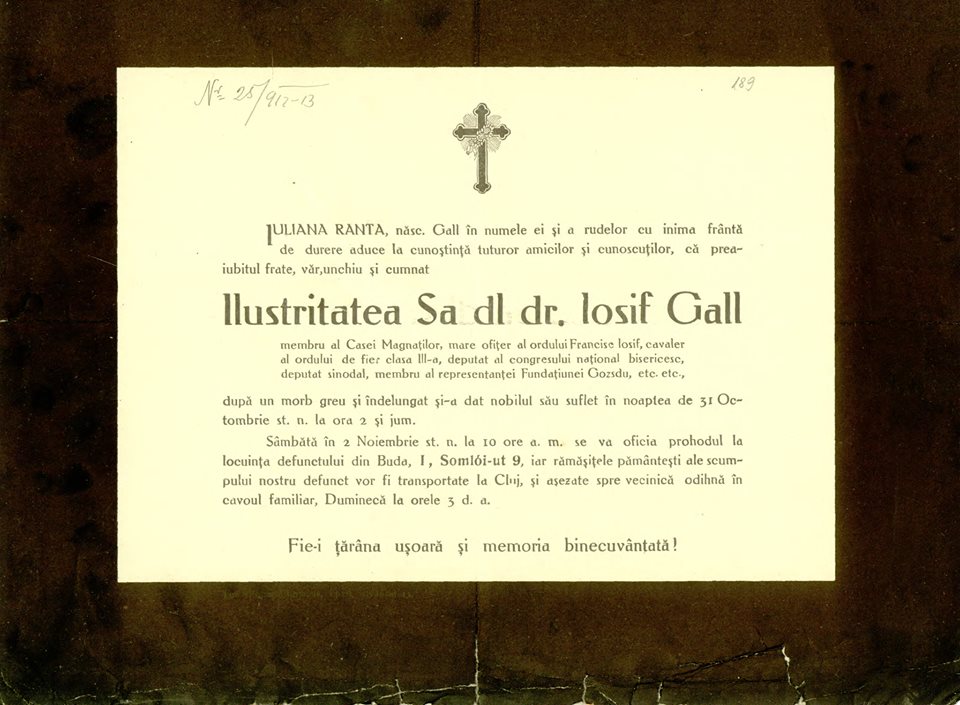

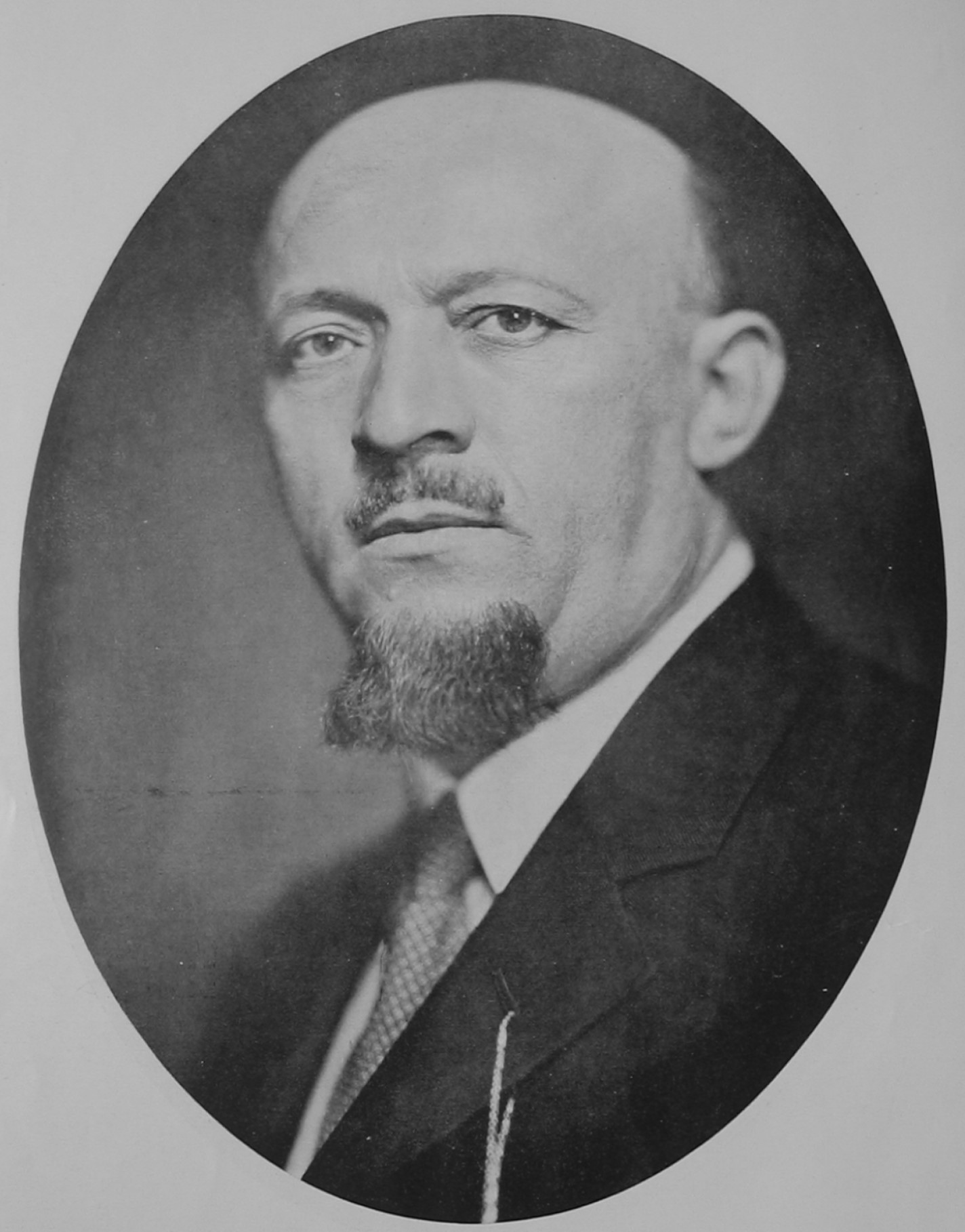

Iosif Gall (1839–1912) – judge, deputy, philanthropist

Iosif Gall (Bistrița-Năsăud County Branch of the Romanian State Archives)

On Christmas Eve in 1870, the Metropolitan Bishop of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania, Andrei Șaguna (1809–1876), wrote to a close friend about the marriage of one of the most valuable jurists of Dualist Hungary of that time, Dr. Iosif Gall:

"What do you know of Gall and his companionship or marriage? I have written to him that Dunca will give his daughter away now with [a dowry of] 12,000 fl. alongside anything that will be left after his death, to be divided into three parts, among his three daughters; and he will not answer me; and Dunca grows impatient, for he wants to know, will anything come of it or nothing? Some people are maddened by good fortune; I fear lest this fate has befallen Gall also."

Iosif Gall (“Octavian Goga” Cluj County Library)

The Romanian high clergyman, an emblematic figure of the national movement in Transylvania, whose influence even reached the circles of the Viennese Court, was concerned with Iosif Gall's fate ever since the latter had been orphaned at the age of 12. Iosif's father, the Orthodox archpriest Grigore Gall (?–1851), had died in 1851, leaving his wife, Carolina (née Stan de Borosjenő) (1814–1904), a widow with four children.

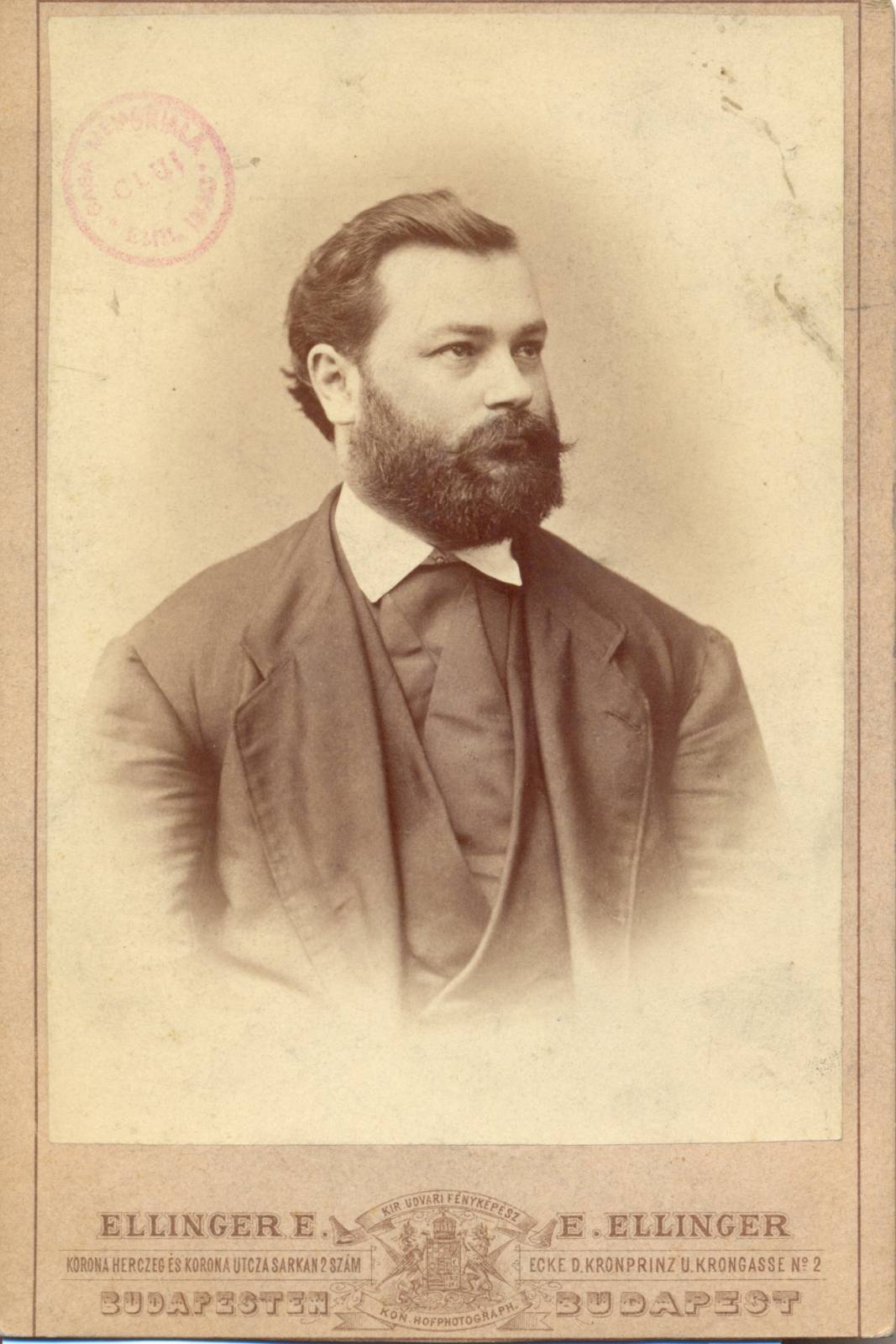

With the support of Andrei, Baron of Șaguna, Iosif Gall had managed to attend secondary school in Cluj (Hu. Kolozsvár) and obtain a higher education at the Academy of Law in Sibiu (hu. Nagyszeben) and the University of Vienna. The metropolitan bishop's support – especially financial support, but not limited to material issues – was fully rewarded by the young Iosif Gall in 1860, when the student was awarded a doctorate in law at the university in the imperial capital.

After finishing his studies, Iosif Gall began his professional career, which progressed at a fast pace, in line with his legal skills and knowledge. In Vienna, for a year after obtaining his doctorate, he completed a compulsory legal traineeship to qualify as a lawyer. Immediately after the end of this period he was appointed as a trainee at the Transylvanian Court of Vienna. Due to his admirable activity, he was shortly afterwards promoted to a superior office within the same institution. In 1867, with the administrative changes brought by the Ausgleich, Iosif Gall was transferred to the Royal Hungarian Ministry of Justice. A year later, in 1868, he was transferred again to the Transylvanian supreme court, and with its dissolution to one of the higher courts in Budapest (Hu. Hétszemélyes Tábla), where he was assigned to the Transylvanian division. After only one year he was appointed report on the proceedings at the Court of Cassation, and in 1870, when he was only 32 years old, he became a judge at the King’s Bench in Budapest. Shortly afterwards he returned to the Court of Cassation as a counselor.

This period of his life, which was marked by outstanding achievements, also witnessed Andrei Șaguna’s efforts to see him settled from a personal perspective as well as a professional one. In 1871 Gall became engaged to Paulina Dunca, daughter of Paul Dunca (1800–1888) from Sibiu, a former government councilor and MP. The marriage between the two, however, never took place because of disputes between Iosif Gall and Paul Dunca, most probably concerning the young girl's dowry.

Eventually, eight years later, his professional fulfillment was matched by a personal one through his marriage to Ecaterina of Agora (?–1899), a widow who owned important possessions in Banat and Croatia. She had previously been wed to Ioan Dobran, from whom she had inherited an important estate. Ecaterina Gall de Agora came from an old family of Aromanian origin settled in Banat. She was also the owner of a large estate at Lucareț (Hu. Lukarec). In Budapest she enjoyed wide popularity and was considered one of the capital's greatest philanthropists thanks to the balls organized to support the Romanian students at the local university. Seen from the perspective of his wife's social status, Gall's marriage, but especially the break-up of the engagement with Paulina Dunca, shows that the young Romanian jurist had thought out his marriage strategy with the utmost pragmatism.

In fact, the results of this social ascent, which complemented his professional one, leveled the way for his career to divert towards politics. In 1881, Iosif Gall resigned from his post as an adviser to the Court of Cassation and gave up his pension, convinced that he could better serve his nation if he were to work in the political arena. On his retirement from the civil service, he was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown Class III and later the Order of Franz Joseph in the rank of Grand Officer.

In the same year he filed his candidacy for the parliamentary deputy of the Recaș (Hu. Rékas) constituency, Temes county, as a supporter of the government program. After winning the elections, he represented this electoral constituency throughout the whole parliamentary cycle 1881–1884. During this period, he was a member of the Parliament's Justice Committee and its rapporteur. In the elections of 1884, he stood again and managed to win another mandate as a Member of Parliament. The 1884–1887 parliamentary cycle was the last of his career in the Lower House of the Hungarian Parliament, as in May 1887 he was appointed lifetime member of the House of Magnates, the Upper House of the Budapest Parliament. He served in this capacity until the end of his life.

Iosif Gall’s as a magnate (Ovidiu Emil Iudean’s personal archive)

One of the most important political endeavors of Iosif Gall's career was the founding of the Romanian Moderate Party, together with the Orthodox Metropolitan bishop Miron Romanul (1828–1898). The organization of the Moderate conference in Budapest in March 1884 and his financial support for the Viitorul [The Future] gazette, the press organ of the newly founded party, are just two of the reasons for his full involvement in this political project. Despite the failure of the moderates, Gall remained convinced of the need for the Romanian nation in Hungary to adopt a moderate course of cooperation with the Hungarian government to achieve social, cultural and ecclesiastical development.

Iosif Gall died in Budapest on the night of October 17/30 to 18/31, 1912. He was buried in Cluj on October 21/November 3 in the presence of his family and a large public. As he had no direct heirs, in his will he left a large part of his estate, about 600,000 crowns, to set up two foundations, both under the name "Agora-Gall", for cultural and philanthropic purposes. Each of the two was to be administered separately, one by the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania and the other by the Serbian Orthodox Church, residing in Karlovci.

Iosif Gall’s obiturary (Bistrița-Năsăud County Branch of the Romanian State Archives)

Iosif Gall’s grave (Ovidiu Emil Iudean’s personal archive)

Owing to this last grand gesture, as well as all his legal, social-cultural and political activity, his biographer, T. V. Păcățian (1852–1941), rightfully called him "The Lucareț Maecena".

Bibliography:

Păcăţian Teodor V., Iudean Ovidiu Emil, Un mecenat român – dr. Iosif Gall (Cluj-Napoca : Presa Universitară Clujeană, 2012)

Iudean Ovidiu Emil, The Romanian governmental representatives in the Budapest Parliament (1881–1918). Cluj-Napoca : Mega, 2016

Berényi Maria, Personalităţi marcante în istoria şi cultura românilor din Ungaria (secolul XIX) (Giula: Institutul de Cercetări al Românilor din Ungaria, 2013)

Leon Scridon sr. (1863–1942) was born on 27 November 1863 in the commune of Feldru, district of Năsăud, formerly (until 1851) part of the Austrian military frontier in Transylvania. His life and career illustrate both the social mobility within the political and social framework of the Dual Monarchy, in a family with a tradition in local administration, and the opportunities for social mobility opened up by the change of regime in 1919.

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

Link: https://feldru.ro/upload/styles/thumb/thumbs/2013/02/dr.leonscridon.jpeg

His grandfather on his father’s side, Simion Scridon, was a non–commissioned officer in the 17th Border Regiment and mayor of the commune. His father, Teodor Scridon (1834–1920) served eight years in the Habsburg army (1854–1862), rising to the rank of standard bearer. On his return he became mayor of the commune (1865), holding this office almost continuously, sometimes as communal cashier, for 34 years. In 1873 he was one of the founders of the “Feldru Loan and Safekeeping Association”, the first popular bank in the region. In 1863 he married Nastasia Pop, with whom he had five children (three boys and two girls).

Leon Scridon sr. (b. 1863), the eldest of the brothers, attended primary and secondary school in Năsăud, where he graduated from the local gymnasium in 1883. He went on to study law at the University of Cluj/Kolozsvár and obtained his bachelor degree in 1887 and his doctorate in state (administrative) sciences in 1889. During his studies he received a scholarship of 200 Gulden from the “Border Guards’ Funds” (the scholarship funds established from the assets of the former Border Regiment, which were only available to the Grenzer descendants).

In 1893 he married Maria Jarda (1875–1950), with whom he had three children: Ion (b. 1894), Elena (b. 1896) and Leon jr. (b. 1897). Between 1887 and 1922 Leon Scridon sr. pursued an administrative career, first as an official of Bistrița-Năsăud County in the Kingdom of Hungary, then as a county official and prefect in the Kingdom of Romania. In the Kingdom of Hungary, his career followed the linear course of most civil servants of the time. After two years as an administrative trainee (1887–1889), he was appointed notary of the orphanage see (1889–1890), then sheriff (Stuhlrichter/Szolgabíró) (1890–1891), county notary (1892–1906), and chief county notary (1906–1919). Among other things, he was well known locally at the time because his working day started at 5 A.M. In the Kingdom of Romania, opportunities for professional and social advancement increased. Between 1919 and 1921 he was appointed vice-prefect of Bistrița-Năsăud County, and on 29 December 1921 he was appointed prefect of Ciuc County, a position from which he retired a month later, in January 1922, when he reached the age limit required by law (35 years of service).

But this upward path was not without its challenges, especially in the early years after 1918. Immediately after the war, former pre-war Romanian officials retained their positions and many advanced in office (such as L. Scridon sr.), amid the resignation or refuge of Hungarian officials. However, they were not looked upon favourably by the nationalist radicals, who wanted to remove from administrative positions all those who had held office in the former political regime. Even if it did not go that far, the former officials were regarded with distrust. Not only political opponents, but also the armed forces were initially wary of the former officials. A report of the Romanian Volunteer Corps in December 1918 contains a list of public persons of Romanian origin in Transylvania who could be trusted to support the military operations of the Romanian Army in its advance westwards. This list does not include the name of Leon Scridon sr., but it does feature that of his son, Leon Scridon jr., at the time a law student.

Last but not least, the precarious economic conditions in the post-war years made it prone to abuse of office and speculation, with accusations also reaching senior officials. In mid-1919, rumours began to spread about an embezzlement supported by senior officials of Bistrita-Năsăud County, headed by the prefect and vice-prefect, who had allowed the sale, through third party traders of products from the warehouses of the former Habsburg army and had illegally issued export permits for such goods (export meaning that they had been sold outside Transylvania, in Bukovina). The investigation lasted almost half a year and ended with the acquittal of L. Scridon sr., who was reinstated in December 1919. A few months later, on 23 May 1920, amidst the tensions that had built up during the preparations for land reform, a group of 200 or 300 peasants forcibly removed the vice-prefect from office. As 28 of them were arrested, the next day more than 2000 peasants took to the streets in front of the prefect’s office.

The last step in his career, the one towards the position of prefect of Ciuc County, took place in December 1921, right at the end of the Averescu II government (13 March 1920 – 16 December 1921), of which the radical wing of the Romanian National Party, led by O. Goga, was part of. It is possible that his son Leon jr.’s relations with this political grouping contributed to the appointment, and the short period he held the office (just one month) indicates that it was a provisional, almost honorary, position before his retirement.

His relations with the public administration continued after retirement: in 1923 he was president of the county section of the Transylvanian Civil Servants Association, and from 1927 president of the county section of the Pensioners Association.

At the same time, he was also an official of civilian institutions, mostly related to the institutional legacy of the former Border Guards Regiment. He was a member of the General Assembly of the Forestry Funds (1889–1942), a member of the Administrative Commission of the same funds (1896–1923) and an assessor of the commission for the administration of the border guards’ forestry funds. He was also cashier and member of the church committee of the Greek-Catholic parish of Bistrița. Between 1912 and 1913 he took the necessary steps to establish the Romanian Women’s Association in Bistrița, drafted the statutes and was secretary of the Association between 1913 and 1919. His involvement in numerous other associations and charity initiatives was complemented by a similar degree of involvement in the local banking institutions. Between 1904 and 1942 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Aurora” bank in Năsăud, and from 1923 until his death in 1942 he was the manager of the Bistrița branch of the same bank. During 1901–1920 he was a member of the board of directors of the “Bistrițiana” bank (vice-president 1911–1915), and during 1926–1930 a member of the board of directors of “Regna”, a logging company operating in the forests of the border guards communes. He was also a member of the board of directors of the “Hebe” company, which managed the thermal baths in Sângeorz Băi. In short, he had a seat and a say in almost every (if not all) institution that mattered at county level, in all branches of public life, for more than forty years.

When Leon Scridon sr. died in Năsăud, in 1942, part of his family, one of the most respected and well-placed in the former military frontier, was in refuge in Romania after the takeover of Northern Transylvania to Hungary. His son Ion Scridon pursued a medical career. His daughter Elena was married to General Grigore Bălan (1896–1944), who died in 1944 in the battles for the liberation of Transylvania. Leon jr. studied law and at a young age became close to the political group led by Octavian Goga (1881–1938). He was a member of the Romanian Parliament (1937, on the lists of the National Christian Party), secretary of state, then secretary for the Someș land (Ținutul Someș) on behalf of the National Revival Front (1940) and general commissioner for Romanian refugees in Northern Transylvania (1940–1944). After the establishment of communism, he was sentenced twice: once in 1949 by the People’s Tribunal in Năsăud, and a second time in 1955 by the Bucharest Territorial Military Tribunal. He was pardoned and released from prison on 12 September 1955.

The four generations of the Scridon family that succeeded each other between the early 19th and the mid-20th centuries illustrate different patterns of social mobility, at different levels and in different chronological periods and political contexts: the role of tradition and administrative position in what might be called the “rural elite” (Simion and Teodor Scridon); the importance of education for the processes of social mobility taking place from the second half of the 19th century onwards (Leon Scridon sr.); the impact of changes in the political regime on members of the elite (upward in 1919 for Leon Scridon sr., then for his son Leon jr., and downward after 1948 for the latter).

Bibliography

Cornel Grad, Contribuția armatei române la preluarea puterii politico–administrative în Transilvania. Primele măsuri (noiembrie 1918–aprilie 1919), „Revista de Administrație Publică și Politici Sociale”, II, 2010, nr. 4 (5), p. 52–79 (55–56).

Vasile Ilovan, Aspecte ale mișcării revoluționare și democratice în județul Bistrița–Năsăud, „File de Istorie”, II, 1972, p. 167–182 (173–174).

Ironim Marţian, Onisim Filipoiu, Leon Scridon senior (1863–1942), „Buletinul Cercului Științific Plaiuri Năsăudene Bistrița”, IV, 1983, p. 36–59.

Adrian Onofreiu, La cumpăna veacurilor şi a vremurilor. Leon Scridon Sen. în apărarea averilor şi a Liceului Grăniceresc din Năsăud, „Arhiva Someșană”, seria III, 14, 2015, p. 67–85.

Teodor Tanco, Leon Scridon schiţase o istorie nescrisă nici pînă azi, in Teodor Tanco, Virtus Romana Rediviva, vol. 5, Bistrița, 1984, p. 282–286.

Iosif Uilăcan, Leon Scridon, in Adrian Onofreiu, Dan Lucian Vaida (eds.), Convergenţe etnoculturale. In Honorem Mircea Prahase, Cluj–Napoca, Mega, 2012, p. 291–308.

Press

Patria, I, 1919, 5, 7/20 February, p. 1.

România, III, 1940, 573–583, 8 January, p. 2.

Țara, IV, 1944, 910, June 18, p. 3.

Though well-known in Transylvania during his time, Petru Meteș is almost unknown today, unlike his cousin, the historian Ștefan Meteș (1887–1977), or one of his sons, Mircea. Petru’s parents, Simion and Maria Meteș, were peasants from Geomal / Diomal in Alba de Jos / Alsó-Fehér County. They had at least six children who survived childhood: Petru (born in 1883, according to other sources: 1884 or 1886), Nistor (1893–1954), Octavian (?–1943), Iuliana (born ca. 1898), Cornelia (born ca. 1899), and Ioan (born ca. 1901). Simion and Maria were wealthy enough to send Petru and Nistor to study at the Hungarian-language Bethlen College of Aiud/ Nagyenyed.

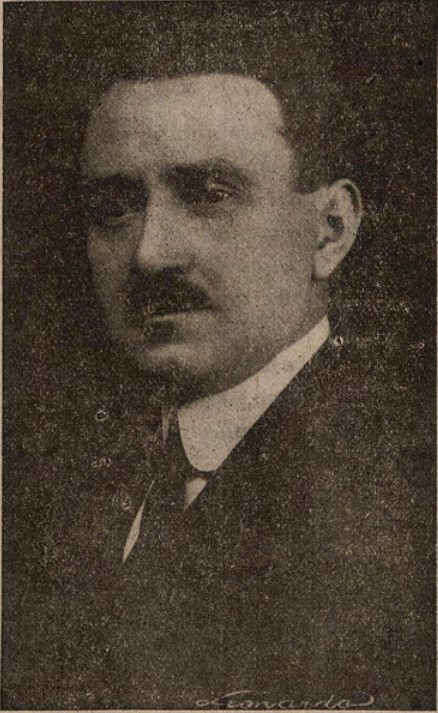

Petru Meteș, prefect of Cojocna (Cluj) county, Cosînzeana, VI, no. 1, 1922, p. 22 (https://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/1506)

Petru Meteș, prefect of Cojocna (Cluj) county, Cosînzeana, VI, no. 1, 1922, p. 22 (https://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/1506)

Ștefan Meteș, historian, MP, and member of the Iorga Cabinet as undersecretary (1931–1932), Anuarul parlamentar, 1931, Bucharest, 1932.

A studious pupil, Petru graduated from secondary school at Bethlen College. He continued his studies at the Franz Joseph University of Cluj / Kolozsvár, where he obtained a degree in Law and a PhD in Legal Science (1908). He did his law internship in Aiud, in the law office of the Hungarian lawyer Pál Szász, the son of József Szász, the főispan (prefect) of Alsó-Fehér County from 1910 to 1917. In 1910, Petru helped Pál Szász to be elected as a deputy in the constituency of Ighiu / Magyarigen – of which Geomal was a part – and whose population was predominantly Romanian. His close relationship with the Szász family helped him to be appointed honorary sheriff in 1910 (tiszteletbeli szolgabiró) and elected as a member of Alsó-Fehér County Congregation “on the Hungarian list” (i.e., on the governing party’s list). Furthermore, in June 1911, P. Meteș was admitted to the Cluj Bar as a lawyer in Aiud.

Město Kluž/ Kolozsvár, pohlednice

Město Kluž/ Kolozsvár, pohlednice

Alongside his connections with the Hungarian milieu, Petru Meteș also integrated into the Romanian society of the time. This seems to have been due to a large degree to his first wife, Iustina Maria Filipan (born ca. 1891–1892, in Bistrița / Beszterce), the daughter of a physician in the district of Năsăud / Naszód. In addition, he joined the local branch of the most important Romanian Association (ASTRA), and was also involved in helping the Orthodox Church.

Everything changed in 1914. Petru was sent to the front line and taken captive by the Russians. In the summer of 1917, he was already a member of the Transylvanian and Bukovinian Volunteer Corps, created within the Romanian Army and made up of Romanian refugees from the Habsburg Monarchy and prisoners of war from the Russian camps. Captain Petru Meteș fought in Moldavia in the summer of 1917 and was later dispatched to Odessa, probably to ensure the security of Romanian refugees and dignitaries. The Bolsheviks under Christian Rakovsky (1873– 1941) imprisoned him there for a short period. Following his liberation, he was hired as one of the three secretaries of the Technical Advisory Board of the Justice Ministry in Chişinău, in Bessarabia, recently integrated into Romania. Following the dissolution of Austria-Hungary and after the Romanians took over local and regional power, he returned to Transylvania where he was appointed as First President of the Dumbrăveni / Erzsébetváros Court of Law and soon transferred to a similar position to the more important Court of Law in Brașov / Kronstadt.

On 15 April 1920, judge Meteș was dispatched by the Ruling Council to fill in the office of prefect for Alba de Jos County. Six months later, Petru Meteș was transferred by the Averescu government and appointed Cojocna (Cluj) County prefect. On 1 January 1921, he was appointed full prefect, which implicitly meant his political involvement within the governing party (the People’s Party), which lacked leaders and members in Transylvania. Through this position, which gave him greater public visibility and enabled him to create a support network, Petru Meteș seems to have tried to find an entryway into politics. He succeeded in keeping the rank of prefect under the brief government of Take Ionescu (December 1921–January 1922) and in the first year of Ion I.C. Brătianu Cabinet. In February 1923, he chose to run for the Chamber of Deputies in the constituency of Ighiu in Alba County as the governmental (National Liberal Party) candidate. The opposition press fiercely attacked his candidacy, mentioning his “anti-Romanian” deeds before 1914. With the help of the local authorities, Petru Meteș won the elections. He served as deputy between 1923 and 1926.

Regarding his personal life, the marriage with Iustina broke up in the mid-1920s. Petru Meteș’s second wife was Victoria Octavia Crișan (born in 1903), the sister of Eugenia, the wife of his brother Nistor. Petru had two children from his first marriage, Mircea Virgil (born in 1912) and Ofelia, nicknamed Lili (born in 1915), and two from his second one, Petre (born in 1927) and Doina (1929).

Although he did not hold any political offices at the national level after 1926, Petru Meteș remained a prominent figure of the Transylvanian Romanian elite due not only to his intense career as a lawyer, but also to his involvement in a Veterans movement and his work in the management committees of various forums of the Transylvanian Orthodox Church. He died in Cluj in January 1946.

Mircea Meteș followed his father’s example: holding a bachelor’s degree and a PhD in Law, he became a lawyer. In 1938, he married Olivia (1913–2001), the daughter of Adam Lula, an Orthodox priest, and the niece of Petru Groza (1884–1958), the Communist choice, in March 1945 for the role of Prime Minister. His relationship with Groza was the leading cause of his career after 1945. Mircea Meteș was hired as head of the Prime Minister’s Secretary Office in 1946. Furthermore, he was admitted to the Foreign Service and soon appointed member of the Romanian mission to Washington. Recalled to Bucharest in 1948, he chose not to return to his homeland and became an opponent of the Romanian government. As a result, his brother and sisters came to be in the cross hairs of the State Security and were under surveillance for a long time.

Bibliography:

The Archives of the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives: files regarding Petru Meteș and his children (Mircea Meteș, Ofelia Zehan, Petru Meteș and Doina Păstrav), folders no.: FI 94683, FI 139103, I 558274, I 574868, SIE 0007226.

Ioan Ciupea, Virgiliu Țârău, Liberali clujeni. Destine în marea istorie, vol. 2. Medalioane, Mega, Cluj-Napoca, 2007, pp. 241-242.

Zoltán Györke, “Prefecții județului Cluj: analiză prosopografică”, in Anuarul Institutului de Istorie „George Barițiu” din Cluj-Napoca. Series Historica, LI, 2012, pp. 305–308. (https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=23237)

Paul Nistor, “Comrade Mircea Meteș: the first communist of the Romanian Legation in Washington (1946-1948)”, in Adrian Vițălaru, Ionuț Nistor, Adrian-Bogdan Ceobanu (eds.), Romanian Diplomacy in the 20th Century. Biographies, Institutional Pathways, International Challenges, Peter Lang, Berlin, 2021, pp. 330-341.

Anton Julius Gschier (1814–1874), lawyer, deputy and mayor

The possibility to penetrate among the political elite of the Habsburg Monarchy in the latter half of the 19th century was significantly influenced by the institutional structure of the Empire and the way in which representatives at various levels of self-government were selected. From the middle of the century, when the first elections to the Imperial Council took place in 1848, and in the following decades, until the electoral reform in 1907 introduced universal suffrage for men, the electoral districts for both the provincial and imperial parliament were usually territorially rather small, always covering only a few neighbouring towns or districts. Especially in the provincial diets electoral districts of the municipal curia in Bohemia often included one town or two towns.

Postcard from Cheb from the nineteenth century.

Within Bohemia, the region of Cheb/Eger, with its natural centre in the town of Cheb, was rather specific. The revival of public life in the spring of 1848 brought with it calls for the restoration of an independent status of the region or even the return of the territory to the Empire. This was also the reason why Cheb citizens refused to elect their representatives to the reformed Bohemian Diet on the grounds that they did not recognise this assembly as their representative body. It is in this context that Anton Julius Gschier, a Cheb native and lawyer, who in the 1840s worked as a Justiziar (official endowed with judicial powers) on the surrounding estates, soon established himself as one of the main spokesmen of the exclusively German speaking Cheb bourgeoisie.

Gschier was born into the family of a Cheb municipal official whose wife was the daughter of one of the first Cheb mayors of the so-called regulated municipal office. Jeremias Gschier (1783–1841) and his wife had only one son, the aforementioned Anton Julius, born on 19 December 1814, more than five years after their wedding. No other children could be traced, nor do they appear on Jeremias’ death notice of 1841. Even so, the clerk’s family was unable to fully provide for their only son’s studies, so Anton was supported by a scholarship intended for the children of Cheb’s burghers.

One year after his father’s death, the young Gschier married the daughter of a local post supervisor and later administrator of the state postal service. No other significant family or kinship ties could be found in the sources available. The key moments shaping his career were the events linked to the abolition of patrimonial administration and the revival of public life in 1848–1849. As a doctor of law and representative of the educated bourgeoisie, Gschier was one of the chief organisers of the burghers’ assemblies that prepared petitions addressed to the Emperor and the government. However, his views apparently clashed with those of the majority of Cheb bourgeoisie representatives. While these venerable patres looked more towards the past and aimed to restore the special status of the town and its surroundings within the Habsburg Empire, Gschier was a progressive and liberally oriented representative of the new intellectual elites. Among other things, he advocated, albeit unsuccessfully, the sending of Cheb representatives to the provincial assembly in Prague. Later, he even recognised the usefulness of optional Czech language instruction at the local grammar school. His views as well as his apparently very uncompromising and vigorous discourse were the reason why he was not as widely recognized and accepted as other local personalities such as the local pharmacist Adolf Tachezi (1814–1892) or the burgher Franz Ernst.

It was the preparation of a petition containing the demands of the town that caused a split in the burghers’ committee elected in March 1848, with Gschier as president. Gschier had vigorously opposed the idea of Cheb’s own Diet or a new convocation of the Cheb Estates, and resigned from the committee in April. Despite his liberal views, still in 1851 Gschier obtained the post of barrister in Cheb, securing thus a permanent presence in the town. By then, Cheb had become a major administrative centre and the seat of new state offices: the district captainship, the regional government, the regional and district court, the grammar school and the chamber of commerce and trade. It was the latter institution that later chose Gschier as its secretary. This post guaranteed him a regular salary, in addition to the income from his legal practice. It also provided him with a range of contacts with like-minded liberal representatives of local industry and commerce.

At the turn of 1851 and 1852, the neighbouring town of Františkovy Lázně was definitively excluded out of the cadastre of the Cheb municipality. As a result, new elections of the municipal self-governing body in line with Stadion’s provisional municipal law could take place. Although Gschier became a member of the municipal committee, his election was not unanimous, and definitely not as unambiguous as that of some other candidates. He received 90 of the 179 votes cast and in the end was not even selected into the more restricted body of councillors, which included a local brewer, a chemist, a doctor and two merchants.

In 1855, Gschier became a town councillor after some members of the committee resigned. Unfortunately, we do not know the exact reasons which brought Gschier back as a leading representative of the Cheb bourgeoisie. It could have been his involvement in the chamber of commerce, his work in the town, where he was one of only three barristers, or his renewed willingness and readiness to participate in the running of public affairs. He immediately began to push his ideas on how the town should function. Among other things, he put through the construction of walking paths and gazebos around the town. He also supported the reconstruction of the St. James Brotherhood Home, a traditional Cheb institution where the poor and old townspeople could live their last years in dignity.

At the beginning of the 1860s, conditions in Austria began to change. The financial crisis, compounded by the disastrous debacle of the Austrian army in northern Italy, forced the Emperor to accept constitutional reform. The renewed elections to the municipal committees confirmed Gschier’s position as one of the councillors and also – and more importantly – as the city’s representative in the newly constituted Bohemian Diet. Before election, Gschier presented himself publicly as a liberal candidate. He declared his support for industry and commerce, vocational education, and the status of municipalities as basic units of self-government. He had to tread carefully, however. Indeed, certain passages of his statement, published by the local newspaper, in which he calls for dampening of passions and setting aside personal interests, show that he was not universally accepted in the town.

As a liberal, he had a rather complicated position in Cheb. Unlike his colleagues and fellow liberal deputies, who strongly opposed the historical Bohemian state law and upheld the centralisation of the Empire, he realized the importance of the historical status of the town for his fellow citizens. Rejecting traditional rights and denying the specific status of the region would certainly not win him many votes. This is why he preferred not to mention this topic at all in his statement. In the end, also thanks to the absence of major opponents, he received 341 votes out of 349 ballots cast. The Bohemian Diet selected him as a member of the Imperial Council and Gschier became one of the representatives in the parliament in Vienna. Thus, in the mid-1860s, Julius Gschier’s political career reached its peak. He was both a provincial and imperial deputy, a city councillor and a member of the district council. At the same time, however, he was already fifty years old and apparently began to experience health problems. These forced him to give up his career as a deputy and return to the settled life of a Cheb burgher. For the candidates from outside Prague and Vienna, work in Parliament entailed frequent travel, staying in hotels, long periods without family or eating outside one’s home, which was not only uncomfortable and expensive, but also caused health complications for many deputies.

Despite that, Gschier did not completely retreat into seclusion. In September 1867, after the previous mayor Franz Ernst refused to continue in his office due to his old age, it was Gschier who was elected mayor by 31 votes out of 35. In his inaugural speech he said that he was at an age where he no longer desired public offices and positions. He also mentioned his health issues. He declared that he accepted the office of mayor only because of his unwavering belief in public life and its importance (Glaube an ein öffentliches Leben). Gschier remained in the office of mayor for two terms. Already in the first few months he proved to be a skilled organiser and a man with a clear vision. He reorganised the municipal office, reforming the functioning of the municipal committee and its specialised commissions. He also introduced new office regulations, revised the market regulations and increased the number of municipal policemen, raising their wages. He also had his own remuneration increased to 1,000 Guldens. At the end of his second term, however, he was progressively left with less and less energy. By 1873 he was virtually absent from the municipal committee meetings where he had to be replaced by the councillor Adolf Tachezy, who also became mayor at the next municipal elections. Anton Julius Gschier died shortly afterwards, on 30 June 1874.

Grave of the Gschier family in Cheb (Wikimedia Commons, author: SchiDD)

Gschier can serve as an example of an individual whose social advance was made possible by his abilities, education, ambition and suitable opportunities. As one of the few legally educated members of the bourgeoisie of the time, he managed to assert himself relatively quickly in the new "constitutional" setting of 1848. Although his belief that it was important to be publicly active and to influence public affairs brought him, on more than one occasion, into conflict with the traditional Cheb bourgeoisie, what ultimately prevailed were his rhetorical skills, his vision of the necessary reforms and the willingness to devote his time and resources to public issues. It is clear that in his public activities Gschier had to rely on the contacts and relationships he had built by himself in the course of his life, but which he could also pass on to his children.

Bibliography

Charmatz, Richard. Österreichs innere Geschichte von 1848 bis 1907: II. Der Kampf der Nationen. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1912.

Judson, Pieter M. The Habsburg Empire: A New History. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Sterneck, Tomáš. “Komplot pomstychtivého pleticháře? Ke kontroverzím vzniku českobudějovického regulovaného magistrátu v roce 1787 [A plot by a vengeful schemer? On the controversies of the establishment of the regulated municipality of České Budějovice in 1787].” Jihočeský sborník historický 89, no. 1 (2020): 73–120.

Šťouračová, Jiřina. “Reformní zásahy Marie Terezie a Josefa II. do městské správy na Moravě [Reform interventions of Maria Theresa and Joseph II in the municipal administration in Moravia].” Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity 50, no. 1 (2003): 169–76.

Velek, Luboš. “’Takový život nestojí za zlámanou grešli!’ Obrázky ze života českých poslanců 19. století [‘Such a life is not worth a broken penny!’ Pictures from the life of Czech parliamentary deputies in the 19th century].” Kuděj. Časopis pro kulturní dějiny 1, no. 2 (1999): 49–63.

Kamila Kaizlová was born in Správčice in eastern Bohemia (today part of Hradec Králové) into the family of an affluent farmer, Adolf Píša (1825–1880).1 Soon after her 20th birthday she moved with her mother Anna (née Böhm) (1829–1896) to what is now the Smetana embankment in Prague.2 Living in Prague allowed her to establish social contacts and even a romantic relationship with Professor Josef Kaizl (1854–1901), 17 years her senior, who was then active as a Young-Czech deputy in the Imperial Council in Vienna. In the 1870s, Josef Kaizl graduated as a lawyer from the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, where he also started to give lectures on economics in 1879. In 1888 he was appointed full professor there, which was an important social position allowing him to consider starting a family. Kaizl and Kamila Píšová had met as early as 1889, but they got engaged only in August 1892 in Gossensaβ in Tyrol3 and eventually married in February 1893, when Josef was 38 and Kamila 21 years old. They had two daughters during their eight-year-long marriage: first-born Kamila (1895–1907) and younger Zdenka (1899–1952). Both their daughters were already born in Vienna, where the family had moved. In Vienna, Josef Kaizl managed to acquire a prominent position on the career ladder when in the spring of 1898 he was rather unexpectedly appointed as Finance Minister in the Cisleithanian government led by Franz Thun-Hohenstein (1847–1916). Kaizl held this position for only a year and half since in autumn 1899 the prime minister resigned. At that time, Josef Kaizl had less than two more years to live. After he suddenly died due to stomach ulcer complications, Kamila Kaizlová became a widow at the age of 30.4

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová, undated (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

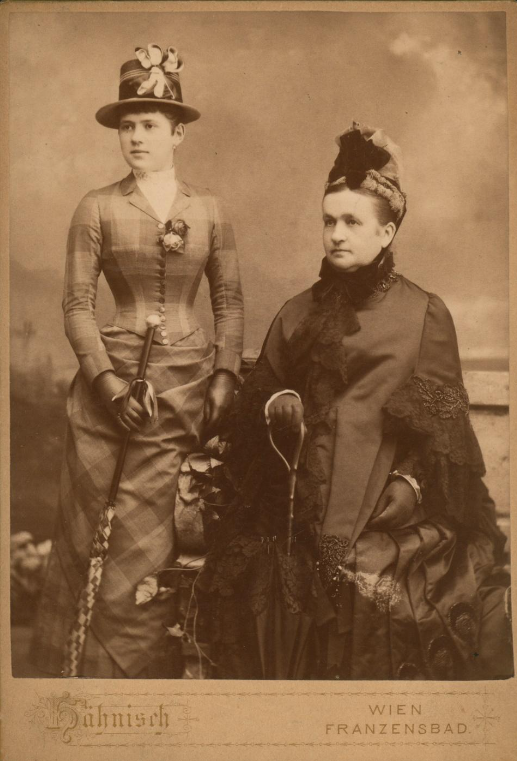

Kamila Pišová with her mother Anna Pišová in the early 1890s (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

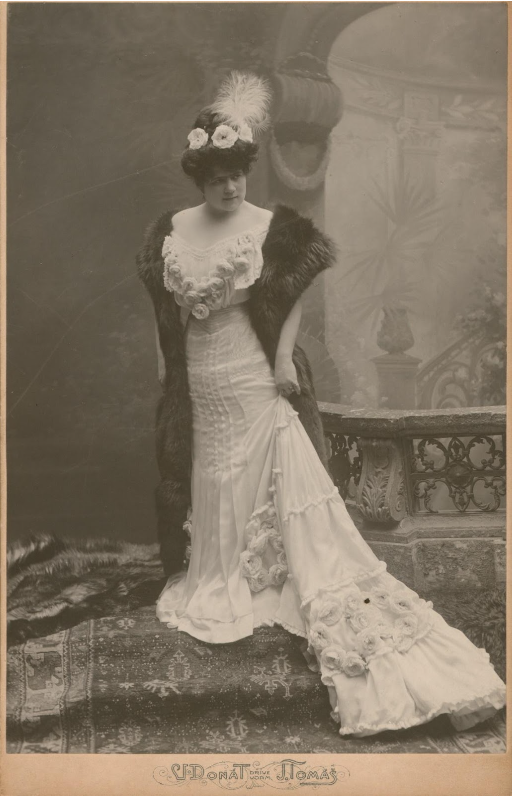

Kamila Kaizlová in a wedding dress in February 1893 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila and Josef Kaizl, June 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters after her husband's death, September 1901 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

Kamila Kaizlová with her daughters, October 1907 (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS, v.v.i., fond Josef Kaizl (unarranged)).

After her husband died Kamila Kaizlová moved from their apartment in the Prague Vinohrady neighbourhood back to Smetana embankment.5 The centrally located flat probably suited her better since one year after her husband’s death she took a rather unorthodox step: she started attending lectures at university. For several reasons, this decision of hers caused a minor sensation in the Prague society. There were not many women in the university lecture halls in the first place, let alone a widow of a distinguished politician looking after two young children. But a more serious reason, causing concern among many an active politician, was the alleged motivation of the ministerial widow. It was rumoured that Kamila Kaizlová was trying to improve her education so that she would be able to sort out and later publish the memoirs of her late husband. It was feared, as the Pilsner Tagblatt newspaper did not hesitate to express, that the “memoirs would contain the actual reasons behind the fall of the Count of Thun and would provide information on the intentions of Kaizl’s politics”.6 Kamila Kaizlová, the newspaper alleged, was to have obtained a special permission from the rector, enabling her to attend lectures on economics, i.e. exactly the same subject that her husband specialized in. In an interview reprinted in the Národní listy, Kaizl’s widow dismissed those speculations: “It is true that I have enrolled as an extraordinary student at the Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university; for instance last year I attended for two hours a week, this year I dedicate eleven hours a week to lectures on art, literature and history. I do not attend any societies, and therefore, this study is my occupation.” As for the publication of the memoirs, she continued: “Such conjectures are ridiculous! You have heard that I do not attend any lectures on political subjects. My husband did leave notes, but no memoirs. To publish them now would be premature since most of the persons mentioned there are still alive. It might perhaps later be possible to publish them as a contribution to recent history. It is not up to me, however, to undertake this task, since I do not have the necessary political knowledge, but up to a professional politician. I did not interfere with politics while my husband was still alive, neither will I do so now, after his death.”7 Even the Plzeňské listy denied the original information brought by the Pilsner Tagblatt.8 It was Zdeněk V. Tobolka (1874–1951) who eventually started to publish Kaizl’s diaries and correspondence in 1908.9

By coincidence, at that time Kamila Kaizlová’s name frequently appeared in articles in both Czech and German newspapers. Given that Kamila became widowed at a young age, it was to be expected that she would not live without a stable relationship forever. In 1908 she got engaged to Fedor Gyrgiewicz, 13 years her junior, lieutenant of the 13th Dragoon Regiment, allegedly an illegitimate son of the late Serbian king Milan I. Obrenovic (1854–1901).10 Accompanied by her fiancé, on Saturday 11 July 1908 Kamila attended the so-called flower parade, with horse-drawn carriages decorated with flowers passing through the streets of Prague. The parade, which attracted around thirty thousand spectators, eventually reached the exhibition area in the Royal enclosure where a tragedy occurred. The horse that was pulling the carriage driven by none other than F. Gyrgiewicz, where his fiancée was also seated, bolted. As a result, the reins got torn, the shaft broke and the whole carriage keeled over. The frightened horse threw itself onto the crowd of onlookers, causing a tragedy with one person dead and 18 gravely injured (Kamila Kaizlová herself got away unscathed). The one victim, moreover, was Jindřiška Slavínská (1843–1908), a popular former actress of the National Theatre.11 The Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on that occasion could not suppress the fact that both the actress’s father, the writer Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg (1809–1858), as well as her grandfather, Johann Ritter of Rittersberg (1780–1841), had died in accidents involving horses.12 During the criminal proceedings that followed F. Gyrgiewicz was eventually found not-guilty,13 but several days after the unfortunate incident he cancelled his engagement to Kamila.14

The young widow, however, did not remain alone for long. Again, she established a relationship with a man much younger than herself, Richard Preiss (1882–1967), son of the writer Gabriela Preissová (1862–1946). Richard Preiss had just freshly graduated from the Faculty od Law of the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University and worked as a trainee at the Czech Financial Prosecutor’s office.15 Their relationship eventually led to marriage, with the wedding taking place in late June 1910 in Baška on the Croatian island of Krk. However, the more than ten-year age difference between the two spouses probably resulted in a rather tumultuous relationship, and in September 1910, a mere three months after their wedding, newspapers brought the news of Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová applying for divorce “from bed and board”, which was granted by the Prague district court on 28 October 1910.16 The separation between the two spouses, however, was not yet complete since in line with the current law divorce was only the first step needed to dissolve the marriage. Even after they divorced, Richard Preiss occasionally visited Kamila, as transpires from the diaries kept by her younger daughter Zdenka.17 Sadly, not even the birth of their daughter Adriena (1914–2009), not long after World War I broke out, could bring the couple closer together. In the end, after the separation became definitive, Richard Preiss remarried, this time at a civil ceremony, taking for his wife Marie Menčíková-Trnková (1888–after 1952), who was also previously separated. But even this marriage broke up in 1932. Soon after, Richard Preiss, who at that time worked as a lawyer in Strážnice, married for the third time, taking for his wife Věra Ploskalová (1907–1995), 25 years his junior, the daughter of a citizens’ savings bank director in Hodonín. Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová did not live to see that third wedding since in April 1930 she died of chronic nephrosclerosis, making it possible for her ex-husband to have a church wedding.

Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová spent the years after divorcing her second husband in the company of her two daughters, Zdenka and Adriena – the eldest, Kamila, having died already in 1907, not yet twelve years old, of a serious pneumonia. She lived on a pension awarded to her after her first husband’s death, which she was able to keep even after she remarried. Immediately after Kaizl’s death the pension amounted to 6,000 crowns a year, with her children receiving another 1,200 crowns a year. After the birth of Czechoslovakia the amount remained unchanged, despite the war inflation, until 1928, when upon request by President Masaryk it was raised to 18,000 Czech crowns.18 However, since Kamila came from an affluent family, she was also paid interest on her own property, which, based on records from 1926, allowed her to maintain a fully equipped four-room apartment and employ a maid-servant.19

By then Kamila Preissová-Kaizlová lived only with her youngest daughter Adriena. Her daughter Zdenka moved out of the Smíchov apartment late in 1921, when she married Professor Josef Blahož (1888–1934), a consul at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former officer of the Legion in Russia.20 In 1925–1931 Josef Blahož worked as counsellor at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Berlin, where the spouses maintained a lively social life and established close contact, among others, with the family of the German diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882–1951), father of the future German President, Richard von Weizsäcker (1920–2015). At one point in time, Kamila herself considered leaving for Berlin and joining her daughter’s family there.21 But in November 1921 she was hospitalized with apoplexy at a sanatorium in Santoška in Prague and spent the last months of her life worrying about the future of her fifteen-year-old daughter Adriena. At that time, Adriena stayed alternately with her father and her grandmother, Gabriela Preissová, and following their mother’s death, Zdena Blahožová also joined in taking care of her half-sister. In 1935 Adriena decided to move permanently to the USA where her father’s sister Gabriela (1892–1981) lived, married to Charles Edward Proshek (1893–1957), medical doctor and Czechoslovak consul in Minneapolis in Minnesota. Adriena never came back to Czechoslovakia.22

Even though Kamila Kaizlová spent only a lesser part of her life beside Josef Kaizl, who undoubtedly belonged among elite Czech politicians, her social position was firmly grounded in her marriage to him and she could draw from it until her last days. She maintained contacts with top Czechoslovak politicians – including Karel Kramář and T.G. Masaryk – and managed to marry her daughter Zdenka into those circles. The press called her Your Excellency and her name was usually followed by the words „widow of the Finance Minister“, even after she remarried and divorced again.

1 State regional archives in Hradec Králové, Collection of registers of the Eastern Bohemian Region, Parish of the Roman-Catholic church in Pouchov, sign. 134-7662, p. 601.

2 They lived in house No. 334 on what then was called Franz embankment (today Smetana embankment, n.334/4): National archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 464, picture 885.

3 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/1., Praha 1915, p. 56.

4 Kaizl’s illness and death are described in detail by Zdeněk Tobolka: Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života III/2., Praha 1915, p. 1180–1181.

5 In the last years of Kaizl’s life the family lived in Italská street, No 1219/2. After becoming a widow Kamila moved to Smetana embankment No 1012/2: National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 59; National Archives, Police directorate I, residence permit applications, carton 247, picture 58.

6 „Die Memoaren werden auch die wahren Ursachen für den Sturz des Grafen Thun enthalten und ebenso Aufschlüsse über die Intentionen der Politik Kaizls geben.“ In: Pilsner Tagblatt III/304, 12. 11. 1902, p. 4.The same news item was also reprinted by, among others Innsbrucker Nachrichten 250, 12.11.1902, p. 5.

7 Národní listy 42/312, 13.11.1902, p. 3.

8 Plzeňské listy 38/261, 14.11.1902, p. 2.

9 Zdeněk V. Tobolka (ed.), JUDr. Jos. Kaizl: Z mého života I.-III., Praha 1908–1915.

10 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3067, 14.7.1908, p. 2.

11 Našinec 44, 15.7.1908, p. 3.

12 Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung 3072, 19.7.1908, p. 6 . In reality, however, Ludvík Ritter of Rittersberg died ten years later than reported by the newspaper. – 6. 6. 1858.

13 Národní listy 48/287, 18. 10. 1908, p. 5.

14 Plzeňské listy 44/164, 21.7.1908, p. 4.

16 Mährisches Tagblatt 31/217, 24.9.1910, p. 7.; Leitmeritzer Zeitung 40/86, 1.11.1910, p. 13.

17 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016.

18 Ibidem, p. 10.

19 Ibidem, note 14, p. 125.

20 Before she got married she lived at what is today Nad Mlynářkou street, No 447/4. Archives of the capital city of Prague, Collection of registers, Roman-Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas in Smíchov, SM O25, fol. 3.

21 Dagmar Hájková – Helena Kokešová (eds.), Dívčí deníky Zdenky Kaizlové z let 1909–1919. Praha 2016, p. 11.

22 Ibidem.