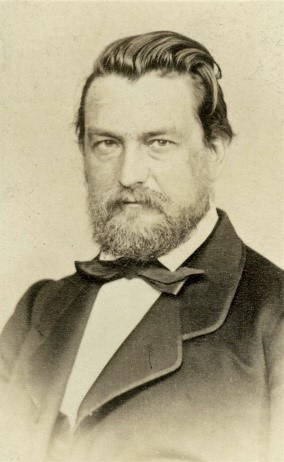

Klement Bachofen von Echt did not belong among the prominent political figures of his time. Although he served as a member of no less than two parliamentary bodies – the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in Vienna, his political involvement was chiefly due to his more immediate interest, which was the sugar industry. He won his first mandate in the 1861 elections to the municipal curia (the Varnsdorf district) of the Bohemian Provincial Diet, which subsequently delegated him as a representative of a constitutional German party to the House of Deputies of the Imperial Council. After he purchased the large estates of Svinaře and Lhotka in the Beroun region in 1863, he ran as a candidate only to the landowners’ curiae. He remained in the Imperial Council only until 1869, when he resigned his seat due to his business, which did not allow him to stay in the distant Vienna for a long time. As for the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, with a break in 1870–1872 he served there until 1883.

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

State District Archive of Sokolov, R. Dotzauer, s–1–c

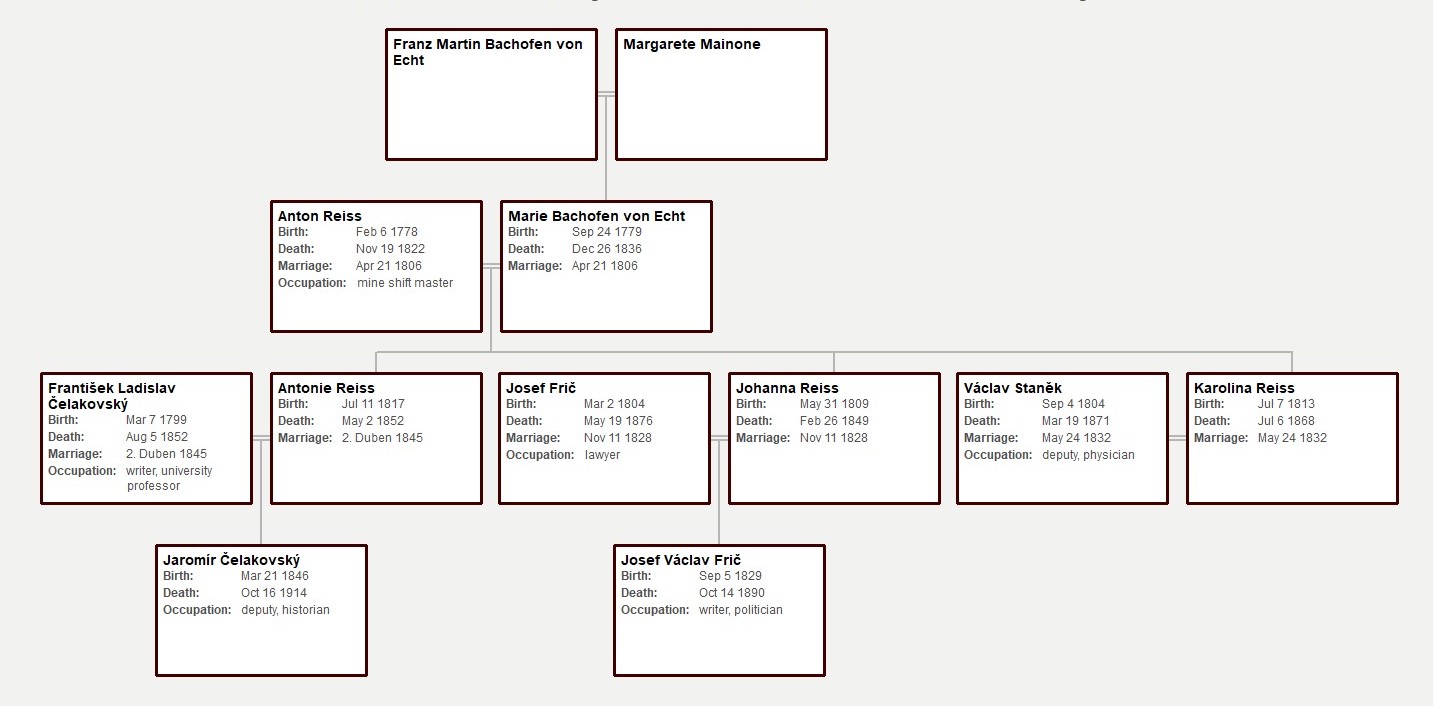

More interesting than Bachofen’s political career is the kinship network that developed around him. It is almost incredible how many public figures, including parliamentary deputies, belonged to the extended Bachofen family. The description of these kinship ties reveals the extraordinary personal interdependence of elite figures active in the 19th century and shows that the elites constituted a very narrow group at that time. It is also not without interest that these kinship ties crossed not only the imaginary ethnic boundaries, but also the provincial ones.

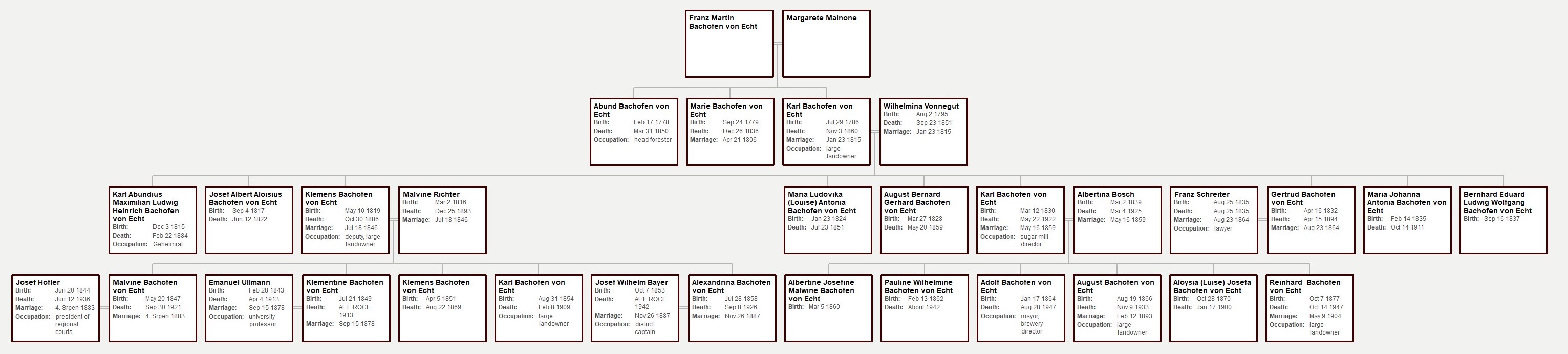

The Bachofen von Echt family has a very long history. They originally came from Limburg, a territory now divided between Belgium and the Netherlands. The family was elevated to nobility sometime at the turn of the 16th century, when it was already residing mainly in Thuringia. However, the geographical scope of its members was much wider. In the 18th century, for example, we find members of the family in the Danish diplomatic service. At the beginning of the 19th century, the first member of the family settled in Bohemia. It was Abund Bachofen von Echt (1778–1850), who came from Ehrenbreitstein near Koblenz, but had to flee after he become involved in a plot against Napoleon. He found refuge in the service of the Archbishop of Prague, on whose estate in Rožmitál pod Třemšínem he served as head forester. His friend Anton Reiss (1778–1822), who together with Abund had taken part in the same conspiracy, also left the Rhineland and settled on the estate of Rožmitál pod Třemšínem, where he served as mine shift master. In 1806 he married there Abund’s sister Marie (1779–1836).[1] This marriage proved to be crucial for the Czech patriotic society, since of the six children born, three daughters, i.e. cousins of Klement Bachofen von Echt, lived to adulthood and all of them married men who played a major role in the Czech society and politics of their time.

The eldest daughter, Johanna Reiss (1809–1849), married the lawyer Josef Frič (1804–1876) in 1828 and became, among others, the mother of the famous revolutionary of 1848, Josef Václav Frič (1829–1890). According to J. V. Frič’s memoirs, his grandparents identified with the Czech society, although they did not learn to speak Czech. Anton Reiss was also allegedly a friend of Jan Jakub Ryba (1765–1815), a prominent Czech composer, who worked as a town scribe and teacher in Rožmitál. After the Reiss family moved to Prague after 1817, they made sure the daughters continued to have a Czech teacher there as well. This is also how the future lawyer Josef Frič, who studied in Prague first at the Faculty of Philosophy and then went on to study law, became acquainted with the family. Josef Frič very soon joined the Czech patriotic society. In 1848, he was a member of the so-called St. Wenceslas (National) Committee and in 1848 won an elected seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, which, however, never met. He became a deputy only after the restoration of constitutionalism in 1861, after which he repeatedly succeeded in defending his seat in the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly on behalf of the Czech National Party in the curia of towns (Prague: Nové Město district) until his death. Reportedly, it was Josef Frič who introduced his peer Václav Staněk (1804–1871), a future doctor who married Karolina Reiss (1813–1868) in 1832, into the Reiss family. Václav Staněk also briefly became involved in politics, when he won a seat both in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Constituent Austrian Imperial Council in Vienna in 1848.

The most important among the Reiss daughters was the youngest Antonia (1817–1852), who is known under the pseudonym Bohuslava Rajská. Antonia was given an education unusual for women at that time. She belonged to the circle of the so-called Czech Budeč school led by Karel Slavoj Amerling (1807–1884). In 1843 she opened a private girls’ school, which was the first not only in Prague but in the whole of Bohemia. In 1845, she married the widowed František Ladislav Čelakovský (1799–1852), a notable poet of the Czech National Revival, who at the time of their marriage was a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Wrocław. They had a son, the Czech legal historian Jaromír Čelakovský (1846–1914), who was active as a Young Czech politician, serving as a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly in 1878–1889 (for the curia of rural communities) and 1895–1911 (for the curia of towns) and as a deputy of the Imperial Council in 1879–1881, 1900 and 1907–1911.

The intimate link of Marie Reiss, née Bachofen von Echt, to the Czech society was rather exceptional compared to other members of her extended family. Her other relatives did not leave the German cultural environment, and, on the contrary, were often considered important protagonists of Germanness of their time. Maria’s younger brother, Karl Bachofen von Echt (1786–1860), settled in North Rhine-Westphalia at the Geist chateau, situated between the towns of Oelde and Ennigerloh near Münster, which had belonged to the Prussian state since 1803. In 1815 Karl married Wilhelmine Vonnegut (1795–1851), the daughter of a princely administrator, with whom he had six sons and six daughters. With the exception of one son and one daughter, all of their offspring lived to adulthood, which was rather exceptional in this period.

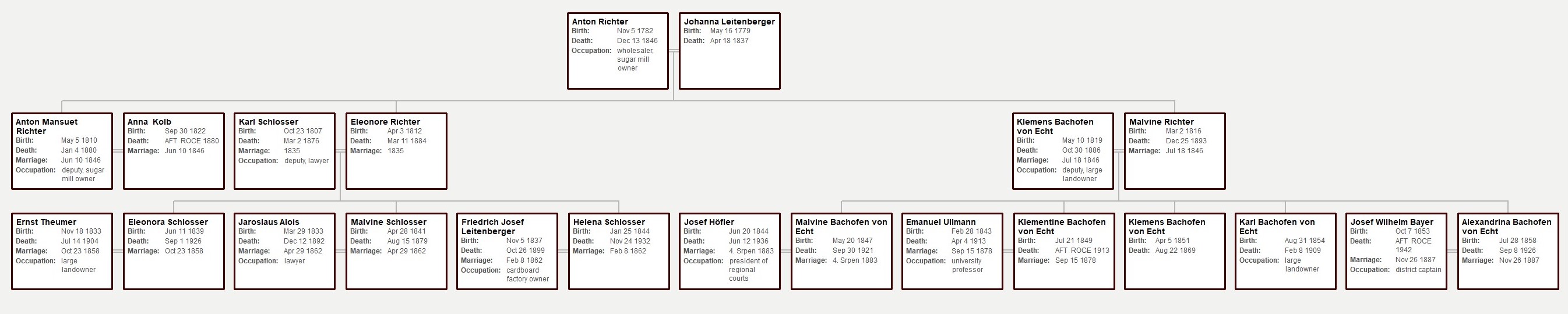

Klement Bachofen von Echt (1819–1886) was born as the third child of Karl and Wilhelmine. Shortly after his twentieth birthday he decided to move to Bohemia to join his uncle Abund, who never married and at that time was the owner of vineyards in Střešovice (now part of Prague). In 1846, Klement managed to conclude a very advantageous marriage. He married the thirty-year-old Malvine Richter (1816–1893), three years his senior, the daughter of Anton Richter (1782–1846), a wholesaler and owner of a sugar mill in (today) Prague’s Zbraslav neighbourhood. Klement thus married into a very interesting family. His brother-in-law was Anton Mansuet Richter (1810–1880), who inherited his father’s sugar factory, but from the second half of the 1860s started to be more interested in politics. In 1867–1878 he was a deputy of the Bohemian Provincial Assembly, representing the Prague Trade and Commerce Chamber in the curia of the chambers of trade and commerce. Through his marriage to Malvine, Klement also became a relative of the Prague lawyer Karel Schlosser (1807–1876), who had been married to Malvine’s older sister Eleonora (1812–1884) since 1835 and sat as a landowner in the Bohemian Provincial Diet and the Imperial Council in 1867–1873. K. Schlosser and Malvine had eight children, and interestingly, as many as three of their daughters married deputies: Eleonora Schlosser (1839–1926) in 1858 married the landowner Ernst Theumer (1833–1904), the cousin of three other deputies (Emil Theumer, Josef Theumer and Leo Theumer), Malvine Schlosser (1841–1879) in 1862 married the Prague lawyer Jaroslav Rilke von Rüliken (1833–1892), and Helena Schlosser (1844–1932), also in 1862, married Friedrich Leitenberger (1837–1899), owner of a cardboard factory in Kosmonosy.

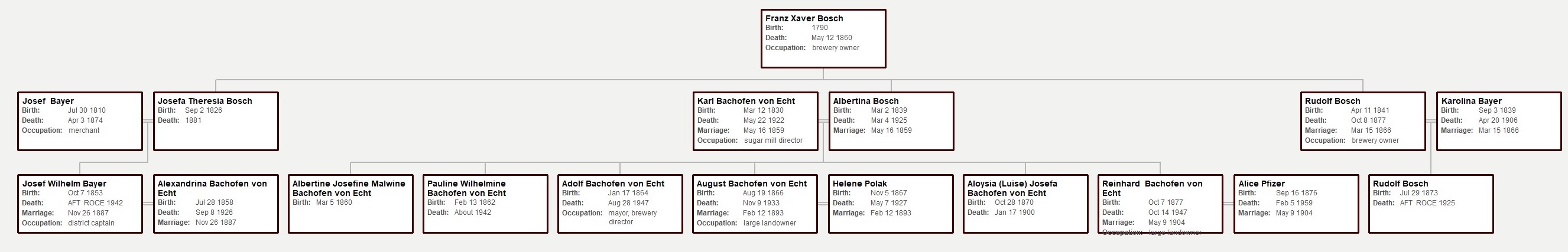

At the latest by 1852, Klement Bachofen became a co-owner of the Zbraslav sugar mill,[2] and soon also of the sugar mill in Líbeznice, north of Prague. Here he was able to take advantage of the expertise of his brother Karl Bachofen (1830–1922), who also moved to Prague to study chemistry at the local university in 1848–1853. After he finished his studies, he took the opportunity to gain practical skill in his brother’s sugar factory, where he worked as managing director until the mid-1860s. After that, however, the two brothers parted ways, since in 1865 Karl moved to Nussdorf in Vienna, where he became involved in his wife’s family business. In 1859 Karl had married Albertina Bosch (1839–1925), daughter of Franz Bosch (1790–1860), owner of the brewery in Nussdorf, Vienna, which eventually became one of the largest breweries in Austria. Through his marriage, Karl became a member of another prominent family clan. By the time Karl Bachofen arrived in Vienna, the brewery had already been taken over by Franz’s son Rudolf Bosch (1841–1877), who in 1866 married Karoline Bayer (1839–1906), daughter of the Prague merchant Josef Bayer (1810–1874). It is not without interest that Karoline’s mother Karoline Kolb (1817–1844) was the sister of the aforementioned Anton Mansuet Richter’s wife. However, the Bosch and Bayer families had already been related before this marriage. After the death of his first wife, Josef Bayer married in 1847 Josefa Bosch (1826–1881), Rudolf’s and Albertine’s own sister. The mutual family ties were sealed in 1887 with the marriage of Josef Wilhelm Bayer (*1853, †after 1942), son of Josef and Josefa, to Alexandrina (1858–1926), daughter of Klement Bachofen. Just before this wedding, J. W. Bayer worked as a district commissioner at the Ministry of the Interior in Vienna, from where he moved to the Bohemian Governor’s Office. Then in 1893 he was appointed a district captain in Česká Lípa.

After the untimely death of Rudolf Bosch, the further destiny of the Nussdorf brewery was shaped mainly by Karl Bachofen. He was subsequently succeeded by his son Adolf Bachofen (1864–1947), who managed the brewery until 1908 and then became chairman of the board of directors of the newly founded joint-stock Liberecko-Vratislavické and Jablonecké breweries company in Vratislavice nad Nisou (Reichenberg-Maffersdorfer und Gablonzer Brauereien Aktien-Gesellschaft in Maffersdorf). Karl Bachofen did not link only his business activities with Nussdorf, he was also very well integrated into the local society and became involved in municipal politics. In 1872–1890 he was the last mayor of Nussdorf before it was incorporated into Vienna, and after the loss of Nussdorf’s independence he was also active in the Vienna municipal council.

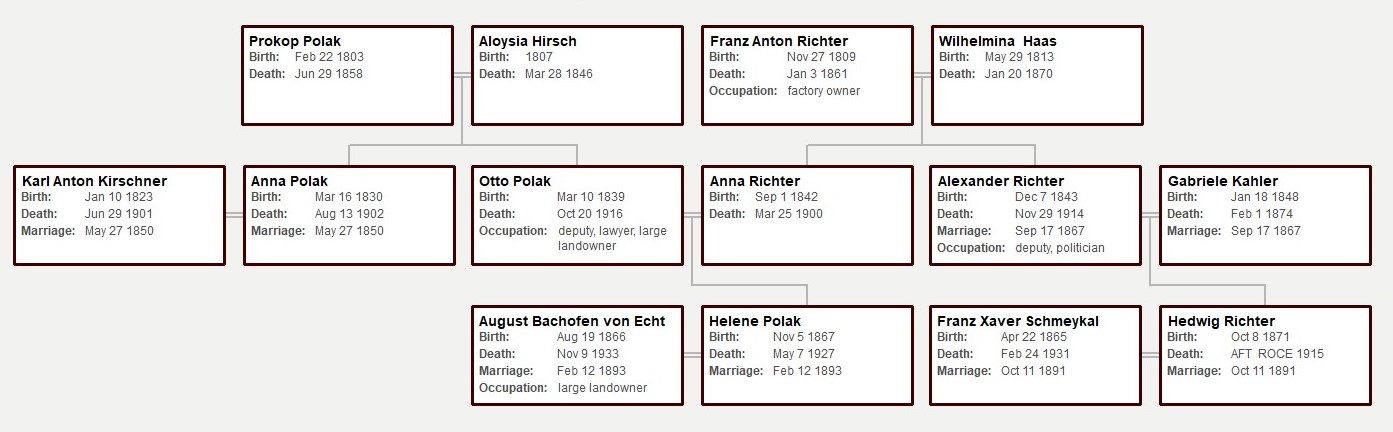

In the nineties the Bachofens established family ties with other prominent German families, since in 1893 Karl’s son August Bachofen von Echt (1866–1933) married Helene Polak (1867–1927), the daughter of Otto Polak (1839–1916), a Prague lawyer and landowner, who in 1879–1897 repeatedly served as a member of the municipal curia of the Imperial Council (Sokolov, Loket district) for a liberal German party. Otto Polak was connected to numerous other deputies. He married Anna Richter (1842–1900), the daughter of Franz Richter (1809–1861), a factory owner in Prague’s Smíchov district. Anna Richter was also the sister of Alexander Richter (1843–1914), who worked in the management of the central Prague German association, the so-called German Casino (Deutsches Haus), and in the 1880s also became involved in politics. In 1883–1889 and then again from 1892 to 1908 he sat in the curia of trade and business chambers at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly for a liberal German party. In 1909–1914 he was also a member of the House of Lords (Herrenhaus). In 1891 Alexander’s daughter Hedwig (b. 1871) married the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1865–1931), who was the son of the lawyer and landowner Franz Schmeykal (1826–1894), who defended the interests of the Constitutionalist Party at the Bohemian Provincial Assembly from 1861 until his death, was the founder and first chairman of the German Casino and was generally regarded as the leader of the Bohemian Germans. It is also interesting to note that Karl Bachofen’s youngest son Reinhard (1877–1947), who owned an estate near Graz, Austria, married Alice Pfizer (1876–1959) in 1904, the daughter of Karl/Charles Pfizer (1824–1906), who left Germany for Brooklyn, USA, where in 1849 he and his cousin founded the future pharmaceutical firm Pfizer.

Of Klement Bachofen’s siblings, his younger sister Gertrude (1832–1894) also moved to Bohemia. In 1864, she married the Prague lawyer Franz Schreiter (1835–1883). Schreiter’s brother-in-law and also schoolmate was the lawyer Alois Funke (1834–1911), who lived in Litoměřice in North Bohemia, where he was mayor in 1893–1911. At the same time, from 1880 until his death, he was a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Litoměřice district) and from 1894 until his death he sat in the Imperial Council, where he defended the interests of a liberal German party.

As for Klement Bachofen himself, in the 1850s he bought a house in Prague’s Old Town, No. 331, on the Franz (today’s Smetana) Embankment, which for several decades became a refuge for his entire family. From the late 1850s onwards, we find Klement in various institutions connected with public life. From 1859 to 1862 he was vice-president of the Chamber of Trades and Commerce in Prague, from 1861 he held a seat in the Bohemian Provincial Assembly and the Imperial Council, in 1862 he became a founding member of the German Casino, and in 1863 he became a concessionaire of the Czech Northern Railway (in 1884–1886 he was its president). In the same period, he also bought the aforementioned estates in Svinaře (Hořovice district) and Lhotka (Kladno district).

It was also a time when Klement’s children began to grow up. In his marriage to Malvine Richter two sons and three daughters were born between 1847 and 1858. All the children lived to adulthood, although his son Klement (1851–1869) died already at the age of eighteen. The second son, Karl (1854–1909), graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Prague, and served, for example, as a member of the board of directors of the Böhmische Escompte Bank (Czech Discount Bank). He never married and lived off the proceeds of the family estates. He was considered a leading representative of German life in Prague, and for many years was also active as secretary of the election committee of the constitutionalist landlords. He met a tragic end when he shot himself in the house on the Vltava embankment in Prague, where he had lived since childhood.

The house at today’s Smetana Embankment No. 331 in Prague’s Old Town

It was in that house that two of Karl’s married sisters also found refuge in adulthood. One was the aforementioned Alexandrina Bayer, the other his eldest sister Malvine (1847–1921), who in 1883 married Josef von Höfler (1844–1936), who at the time of their marriage was a council secretary of the Supreme Provincial Court in Prague and later held the position of president of the regional courts in Most and Česká Lípa. Josef was the son of the well-known German historian Konstantin von Höfler (1811–1897), who first lectured at the University of Munich and then in 1851 was summoned by the Austrian Minister of Cult and Education, Lev Thun, to teach history as a professor at the University of Prague. In 1865–1869, Konstantin Höfler was also a member of the municipal curia of the Bohemian Provincial Diet (Chomutov, Vejprty and Přísečnice districts). In 1871–1872 he returned to the Diet as a „virilist“ given his position of rector of the Karl-Ferdinand University. From 1872 until his death, he was also a member of the House of Lords of the Imperial Council. Klement Bachofen’s last child was his daughter Klementine (*1849, †after 1913), who in 1878 married Emanuel Ullmann (1843–1913), professor of criminal law at the University of Innsbruck, who later also worked at the universities of Vienna and Munich.

An interesting insight into the coexistence of several different households inhabiting house no. 331 in Prague’s Old Town as well as into the housing standards of the Prague elite of the time is offered by the 1890 census, when Klement Bachofen von Echt had already been dead for four years. The house, which at that time belonged to Klement’s widow Malvine, had a total of five housing units. The apartment situated on the ground floor, consisting of one room and a kitchen, was inhabited by the then 62-year-old German-speaking caretaker, who lived there with his wife of the same age and a 26-year-old Czech maid. On the raised ground floor was the apartment of the owner’s son-in-law Josef W. Bayer, which included 6 rooms, 3 cabinets (pantries), 1 hall and 1 kitchen. Apart from J. W. Bayer and his wife, their two children lived there – an almost two-year-old son and a six-month-old daughter – as well as 29-year-old Adolf Bayer, Josef’s brother, who worked as a private forestry clerk. The remaining members of the household were women of the service staff. Two of them were sisters coming from the Benešov region near Prague and spoke German as their vernacular language – the older one, aged 38, was a chambermaid, the younger one, aged 31, worked as a cook. The remaining two girls were hired as nannies – a 33-year-old German-speaking girl from Litoměřice and a 23-year-old Czech-speaking girl from Černý Kostelec. It can be assumed that the Bayers used this apartment from their marriage in 1887 until 1893, when they moved to Česká Lípa for reasons of a career advancement.

The first floor used to be reserved for the most representative apartment. In this case it was a space that consisted of 11 rooms, 1 pantry, 2 halls and 1 kitchen. It was occupied by a total of 15 people. In the first place, the 74-year-old owner of the house, Malvine Bachofen von Echt, lived there. Apart from her, only her 46-year-old son Karl belonged to the family. Other members of the household were the 71-year-old Elise Hiltz (1819–1912), who came from Switzerland (from Courtelles in the canton of Bern) and was assigned the role of companion. The rest of the household consisted of the service personnel: a 33-year-old German-speaking chambermaid from Prague, a 43-year-old Czech-speaking female cook from the Příbram region, a 26-year-old Czech-speaking assistant cook from around Hořovice and a 27-year-old German-speaking male servant from the Podbořany region. The remaining eight persons were members of one Czech-speaking family, whose head was a 37-year-old coachman Václav Soukal (two Wallachian horses were also kept directly in the house). He lived there together with his 39-year-old wife and six children aged from 1 to 16 years, with the remark that their 14-year-old daughter also served as a nanny, although it is not clear what children she looked after. The owners of the house probably met this family in Líbeznice, where Klement Bachofen had a brewery, since that was where the family’s children were born.

The fourth apartment was located on the second floor and consisted of 4 rooms, 1 pantry and 1 kitchen. From 1874 it was occupied by probably an unrelated family of a 62-year-old former inn tenant from the Thuringian town of Schleiz, who lived in the apartment with his 57-year-old wife, a 24-year-old daughter and a 24-year-old maid from the Blatná region. The last apartment, also located on the second floor, had 5 rooms, 1 hall and 1 kitchen. The family of Klement Bachofen’s eldest daughter Malvine, married Höfler, lived there. Although Malvine’s marriage to Josef Höfler at that time had lasted for more than six years, it was childless, so only a 42-year-old female cook from the Domažlice region and a 33-year-old chambermaid from Jindřichův Hradec, both German-speaking, lived in the flat with them.

Ten years later, the occupants of the house changed radically, as Malvine Bachofen von Echt died in 1893 and both her daughters followed their husbands to their new places of work – not only Josef W. Bayer’s family moved to Česká Lípa, but from 1897, after a short one-year intermezzo in Most, Josef Höfler also served in Česká Lípa as president of the regional court. Karl Bachofen von Echt was the only one of his family who continued to live in the house. Even after ten years, the 81-year-old Elise Hiltz still lived in the house, as the only person to keep him company. In the 1900 census, she was described as a housewife. Apart from her, the only other members of the household were a 31-year-old maid and a 32-year-old cook, both of whom stated Czech as their vernacular. It is highly probable that Elise Hiltz remained with Karl Bachofen until his death. She did not die until August 1912, at the age of almost 93, in Vienna. Her death record shows that she used to be a nanny, so it is likely that she raised all of Klement Bachofen’s children, who eventually also took care of her. She spent her last days in the house that was bought by Alexandrina Bayer née Bachofen in 1911, after her husband retired. Alexandrina herself also died there in 1926.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Bachofen family withdrew from the Czech lands after a hundred years of activity. It is true that after the suicide of Klement’s son Karl, Karl’s cousin Adolf, who, like Karl, remained childless, still served as chairman of the board of directors at the Vratislavice brewery. However, from the 1920s Adolf became increasingly interested in palaeontology and at the age of 61 he defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Vienna. Klement’s daughters Alexandrina Bayer and Malvine Höfler also moved to Vienna, where both died.

[1] Frič, Paměti I, Praha 1957, p. 38.

[2] Centralblatt der Land- und Forstwirthschaft in Böhmen, 8 Nummer, 1852, s. 4

Elie Dăianu was a prominent member of the Romanian elite in Transylvania in the first half of the 20th century. Although he had a rich ecclesiastical, publishing, cultural and political activity, he received little attention from historians, remaining somewhat in an undeserved shadow. Elie Dăianu was born on 9 March 1868 in the village of Cut, Alba county. His parents, Iosif Dăianu and Ana Dăianu née Munteanu, were wealthy peasants (his father was a mayor).

Elie Dăianu

Elie Dăianu

Dianu, his parents and his sister, 1890

Elie Dăianu began his studies at the village school, then continued them in Sibiu and Blaj, where he took his baccalaureate in 1888. Among his teachers in Blaj were famous Romanian scholars like Timotei Cipariu (1805–1887) and Ioan Micu Moldovan (1833–1915). Elie Dăianu then went to university in Graz and Budapest, graduating in Theology and Letters; he also obtained his doctorate in Budapest, also in Letters. Elie Dăianu was the only one of his brothers to pursue an intellectual career (he had three sisters and two brothers who remained peasants).

In 1897 Elie Dăianu married Ana Totoianu who came from a family of priests from Micești, Alba county, with whom he had two children, Ioachim Leo and Lucia Monica. Unfortunately, his wife died in 1900, shortly after the birth of his daughter (later, his son Ioachim Dăianu was to make a career as a diplomat, working in various places such as chargé d’affaires at the Romanian embassy in Riga, counsellor at the Romanian embassy in Moscow, Romanian consul general in Tirana etc.).

Elie Dăianu began his cultural and political carreer as a student. While in Budapest as a doctoral student in 1893, Dăianu was elected president of the “Petru Maior” Society, together with Iuliu Maniu (1873–1953) vice-president, Aurel Vlad (1875–1953), Octavian Beju, Octavian Vassu (1873–1935), Axente Banciu (1875–1959). In April 1894, together with Valer Moldovan (1875–1954), Ilie Cristea (1868–1939) (future Orthodox patriarch), Iuliu Maniu and Aurel Vlad, he participated in the Student Congress in Constanța, about which he wrote in the newspaper “Dreptatea”, under the pseudonym Edda; in May of the same year he was part of the press office of the Memorandum process, led by Dr. Vasile Lucaciu (1852–1922) and Septimiu Albini (1861–1919).

After finishing his studies, Elie Dăianu worked for a year (1895) as an editor at the newspaper Dreptatea in Timișoara, then, assigned by Ioan Rațiu (1828–1902), he became director of the “Tribuna” in Sibiu, which he directed between 1896 and 1900. For the next two years, until the summer of 1902, Elie Dăianu was professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology in Blaj. In August 1902 he was appointed priest and protopope of Cluj, a position he held until his retirement in 1930. At the same time, he carried out an intense cultural and political activity. In addition to articles on important current issues, he published writings and translations of literature, history, philosophy and poetry in numerous newspapers from Bucharest, Budapest, Cluj, Sibiu, Arad, Brașov etc; in 1903 he founded a new magazine in Cluj, “Răvașul”.

Elie Dăianu was an important member of the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and Culture (ASTRA), founded in 1861 in Sibiu as the first central cultural institution of the Romanians of Transylvania, which played an important role in the cultural and political emancipation of the Romanian nation in Transylvania. Elie Dăianu was first a scholarship holder of ASTRA while he was a student in Blaj; later, he became involved in ASTRA’s activities, wrote educational brochures and books, held popular conferences, and even became a member of its Central Committee.

Before 1918, when Transylvania was still part of Hungary, the ideas expressed by Elie Dăianu in newspapers were considered provocative by the Hungarian authorities who sentenced him to one year in prison in Cluj and then to deportation to Sopron in Hungary. The end of the war and the union of Transylvania with Romania brought an end to Elie Dăianu’s exile.

He participated in the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia as a delegate of the Cluj diocese; at the same time, he was the president of one of the electoral circles in Cluj that appointed delegates to this assembly. Later he joined the People’s Party, together with Octavian Goga (1888–1938) and Vasile Goldiș (1862–1934), being elected deputy in the Romanian Parliament in 1920 and vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies; the president was Duiliu Zamfirescu (1858–1922), former collaborator of his magazine “Răvașul” from Cluj. He was involved in politics until 1926, serving several terms as deputy and senator. At the same time, from 1921 to 1938, Elie Dăianu was a member of the Historical Monuments Commission - Section for Transylvania, which had the task of cataloguing and monitoring architectural and artistic monuments.

After his retirement, Elie Dăianu continued to publish articles on literature, history, theology, etc. In the last part of his life, he suffered material hardship due to the withdrawal of his pension by the communist regime on the pretext that he was a forest owner. In his later years he was supported by his son Ioachim, who was also living modestly after his diplomatic career was ended by the communist regime.

Sources:

Literature:

Valentin Orga, Din zile de detenție. Însemnările lui Elie Dăianu din anii 1917–1918, in “Revista Bistriţei”, XVII, 2003, P· 247–265.

Ilie Moise, Ilie Dăianu şi spiritul Blajului, in “Transilvania”, 5/2010, p. 73–78.

Gheorghe Naghi, Din însemnările inedite ale dr. Elie Dăianu (1917–1918), in “Ziridava”, XI, 1979, p. 1089–1097.

Robert Marcel Hart, Raluca Maria Viman, Un mare cărturar și publicist ardelean: Elie Dăianu (1868–1956), in “Caiete de Antropologie Istorică”, 2018, p. 42–50.

Press :

“Gazeta Transilvaniei” no 180/18 August 1902.

“Răvașul” no. 4/23 ianuarie 1904.

Elie Dăianu was a prominent member of the Romanian elite in Transylvania in the first half of the 20th century. Although he had a rich ecclesiastical, publishing, cultural and political activity, he received little attention from historians, remaining somewhat in an undeserved shadow. Elie Dăianu was born on 9 March 1868 in the village of Cut, Alba county. His parents, Iosif Dăianu and Ana Dăianu née Munteanu, were wealthy peasants (his father was a mayor).

Elie Dăianu

Elie Dăianu

Dianu, his parents and his sister, 1890

Elie Dăianu began his studies at the village school, then continued them in Sibiu and Blaj, where he took his baccalaureate in 1888. Among his teachers in Blaj were famous Romanian scholars like Timotei Cipariu (1805–1887) and Ioan Micu Moldovan (1833–1915). Elie Dăianu then went to university in Graz and Budapest, graduating in Theology and Letters; he also obtained his doctorate in Budapest, also in Letters. Elie Dăianu was the only one of his brothers to pursue an intellectual career (he had three sisters and two brothers who remained peasants).

In 1897 Elie Dăianu married Ana Totoianu who came from a family of priests from Micești, Alba county, with whom he had two children, Ioachim Leo and Lucia Monica. Unfortunately, his wife died in 1900, shortly after the birth of his daughter (later, his son Ioachim Dăianu was to make a career as a diplomat, working in various places such as chargé d’affaires at the Romanian embassy in Riga, counsellor at the Romanian embassy in Moscow, Romanian consul general in Tirana etc.).

Elie Dăianu began his cultural and political carreer as a student. While in Budapest as a doctoral student in 1893, Dăianu was elected president of the “Petru Maior” Society, together with Iuliu Maniu (1873–1953) vice-president, Aurel Vlad (1875–1953), Octavian Beju, Octavian Vassu (1873–1935), Axente Banciu (1875–1959). In April 1894, together with Valer Moldovan (1875–1954), Ilie Cristea (1868–1939) (future Orthodox patriarch), Iuliu Maniu and Aurel Vlad, he participated in the Student Congress in Constanța, about which he wrote in the newspaper “Dreptatea”, under the pseudonym Edda; in May of the same year he was part of the press office of the Memorandum process, led by Dr. Vasile Lucaciu (1852–1922) and Septimiu Albini (1861–1919).

After finishing his studies, Elie Dăianu worked for a year (1895) as an editor at the newspaper Dreptatea in Timișoara, then, assigned by Ioan Rațiu (1828–1902), he became director of the “Tribuna” in Sibiu, which he directed between 1896 and 1900. For the next two years, until the summer of 1902, Elie Dăianu was professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology in Blaj. In August 1902 he was appointed priest and protopope of Cluj, a position he held until his retirement in 1930. At the same time, he carried out an intense cultural and political activity. In addition to articles on important current issues, he published writings and translations of literature, history, philosophy and poetry in numerous newspapers from Bucharest, Budapest, Cluj, Sibiu, Arad, Brașov etc; in 1903 he founded a new magazine in Cluj, “Răvașul”.

Elie Dăianu was an important member of the Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and Culture (ASTRA), founded in 1861 in Sibiu as the first central cultural institution of the Romanians of Transylvania, which played an important role in the cultural and political emancipation of the Romanian nation in Transylvania. Elie Dăianu was first a scholarship holder of ASTRA while he was a student in Blaj; later, he became involved in ASTRA’s activities, wrote educational brochures and books, held popular conferences, and even became a member of its Central Committee.

Before 1918, when Transylvania was still part of Hungary, the ideas expressed by Elie Dăianu in newspapers were considered provocative by the Hungarian authorities who sentenced him to one year in prison in Cluj and then to deportation to Sopron in Hungary. The end of the war and the union of Transylvania with Romania brought an end to Elie Dăianu’s exile.

He participated in the Great National Assembly in Alba Iulia as a delegate of the Cluj diocese; at the same time, he was the president of one of the electoral circles in Cluj that appointed delegates to this assembly. Later he joined the People’s Party, together with Octavian Goga (1888–1938) and Vasile Goldiș (1862–1934), being elected deputy in the Romanian Parliament in 1920 and vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies; the president was Duiliu Zamfirescu (1858–1922), former collaborator of his magazine “Răvașul” from Cluj. He was involved in politics until 1926, serving several terms as deputy and senator. At the same time, from 1921 to 1938, Elie Dăianu was a member of the Historical Monuments Commission - Section for Transylvania, which had the task of cataloguing and monitoring architectural and artistic monuments.

After his retirement, Elie Dăianu continued to publish articles on literature, history, theology, etc. In the last part of his life, he suffered material hardship due to the withdrawal of his pension by the communist regime on the pretext that he was a forest owner. In his later years he was supported by his son Ioachim, who was also living modestly after his diplomatic career was ended by the communist regime.

Sources:

Literature:

Valentin Orga, Din zile de detenție. Însemnările lui Elie Dăianu din anii 1917–1918, in “Revista Bistriţei”, XVII, 2003, P· 247–265.

Ilie Moise, Ilie Dăianu şi spiritul Blajului, in “Transilvania”, 5/2010, p. 73–78.

Gheorghe Naghi, Din însemnările inedite ale dr. Elie Dăianu (1917–1918), in “Ziridava”, XI, 1979, p. 1089–1097.

Robert Marcel Hart, Raluca Maria Viman, Un mare cărturar și publicist ardelean: Elie Dăianu (1868–1956), in “Caiete de Antropologie Istorică”, 2018, p. 42–50.

Press :

“Gazeta Transilvaniei” no 180/18 August 1902.

“Răvașul” no. 4/23 ianuarie 1904.